Brown is a composite color, made by combining complementary hues—a warm neutral. It’s only itself when contrasted with a brighter shade; fuschia or aqua always appear so, while brown is brown only in comparison to another color; its visibility is dependent on the color next to it. Over centuries, brown’s association has changed from one with poverty and drab rusticity to virtue and wholesomeness—softly wrinkled brown paper bags for simple school lunches; the conscientious consumer opting for brown rice or sugar or toast over white; unrefined, unbleached napkins.

Beige. Elegant and dispassionate, beige has the warmth of brown and the coolness of white, and, like brown, is often dull—a background shade. Another chameleon, its perception is mediated by what’s adjacent; its temperature is unstable.

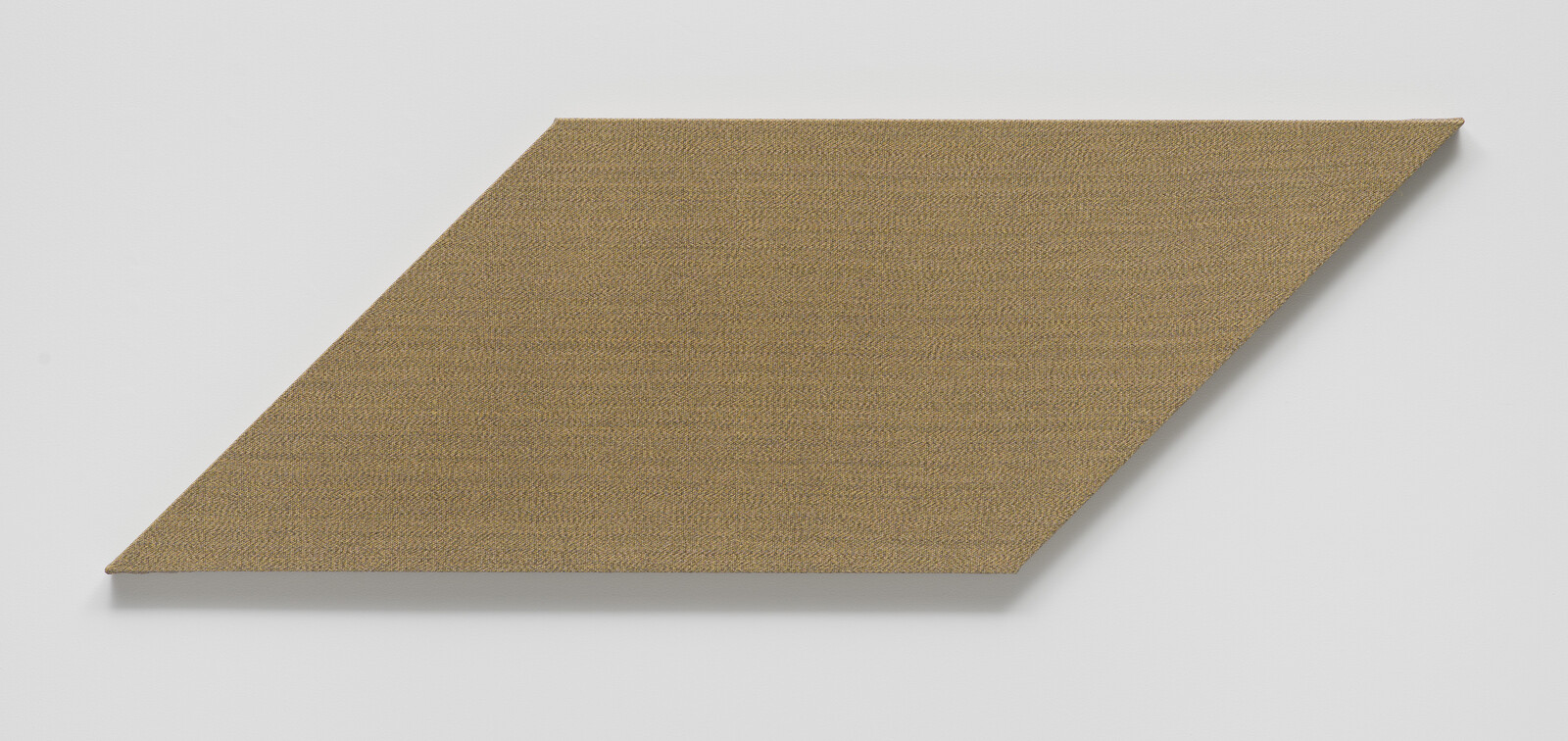

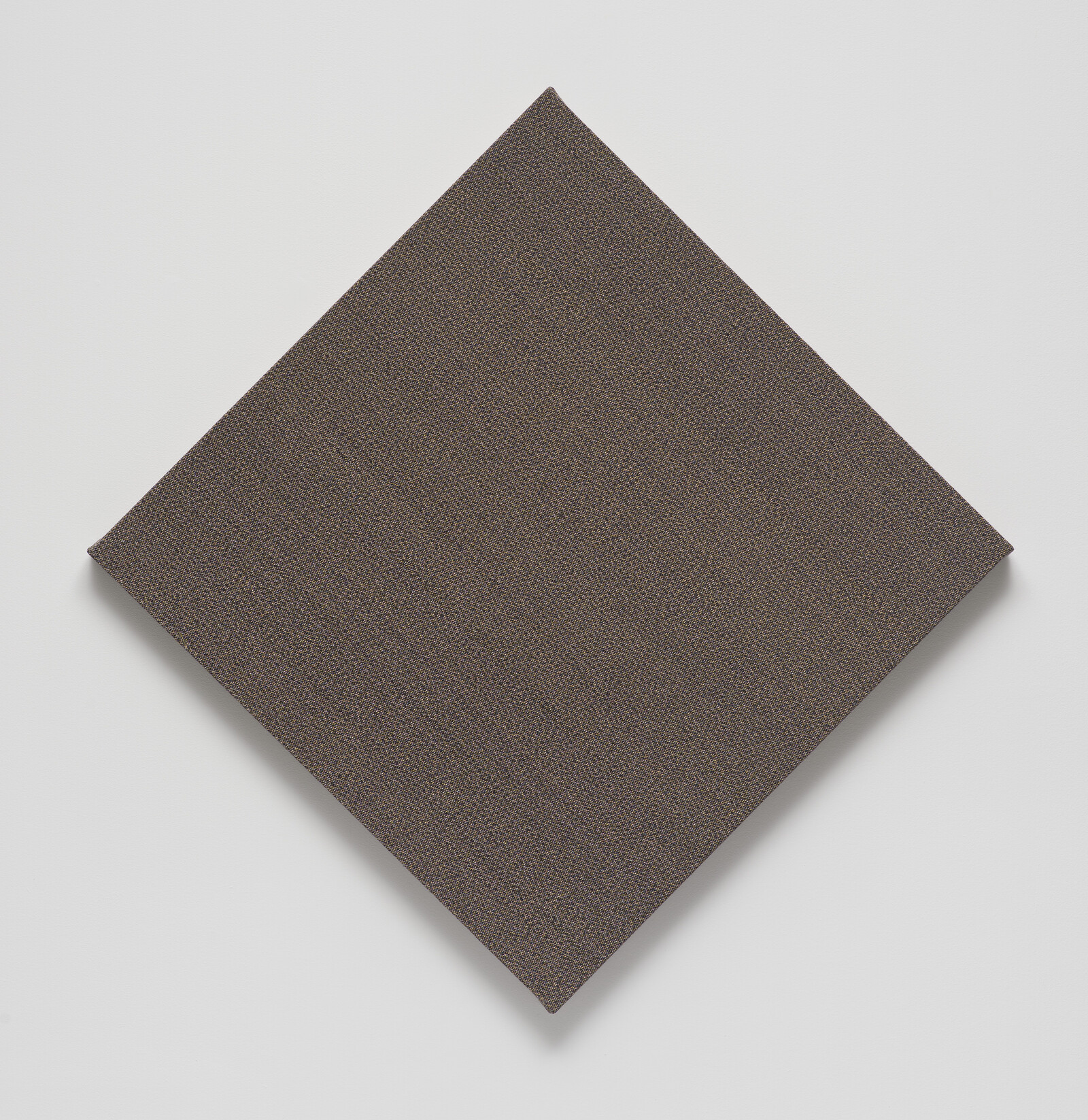

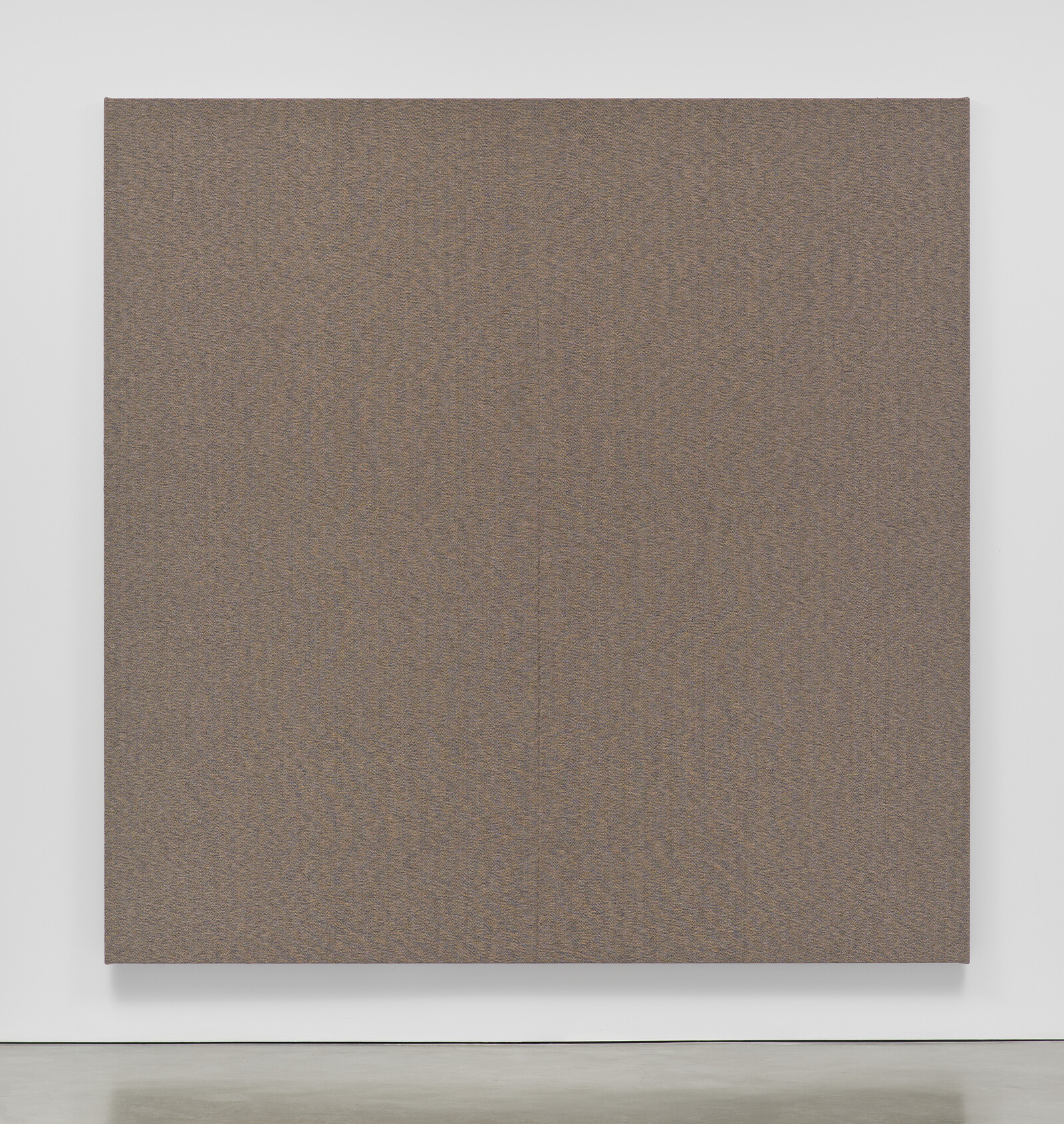

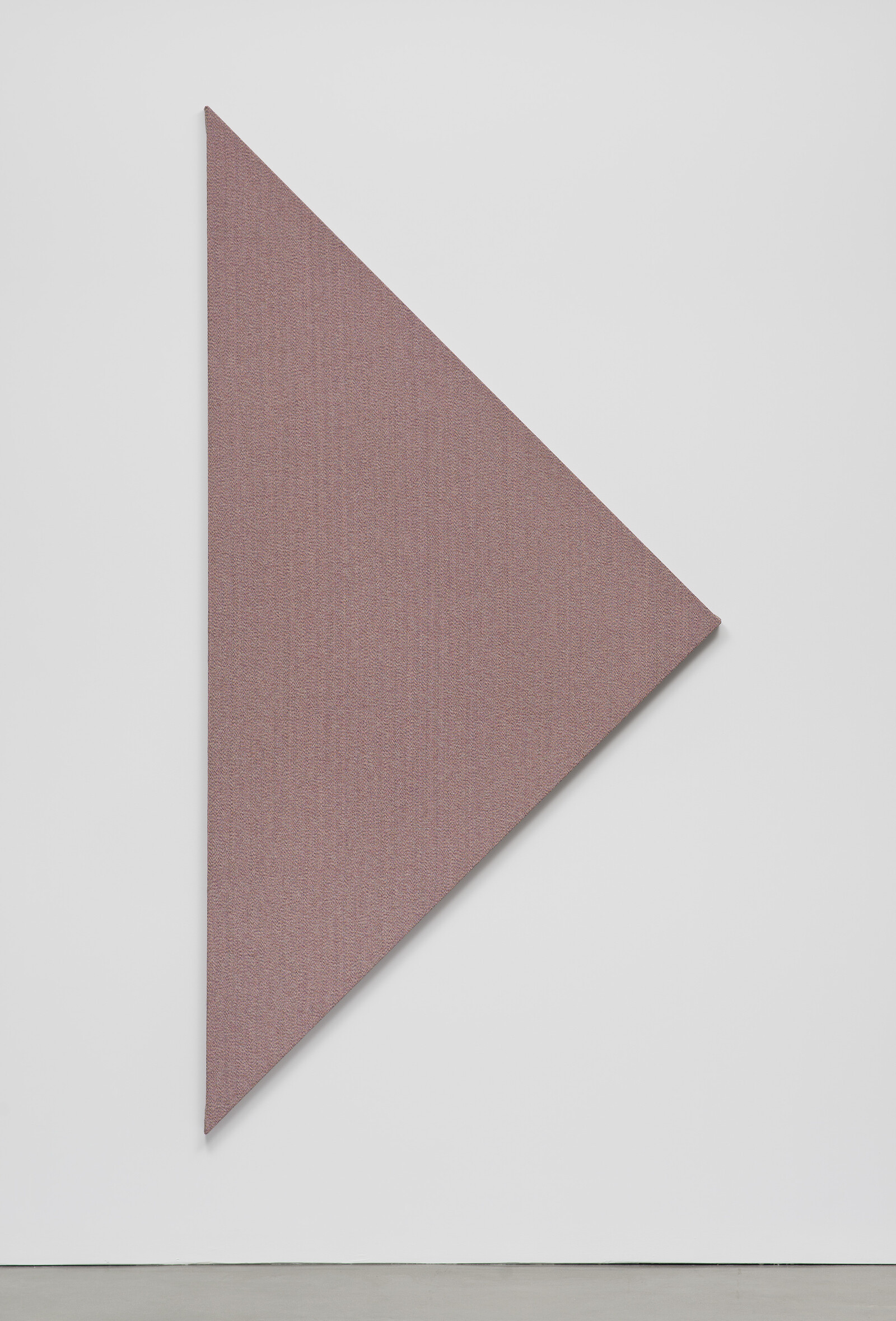

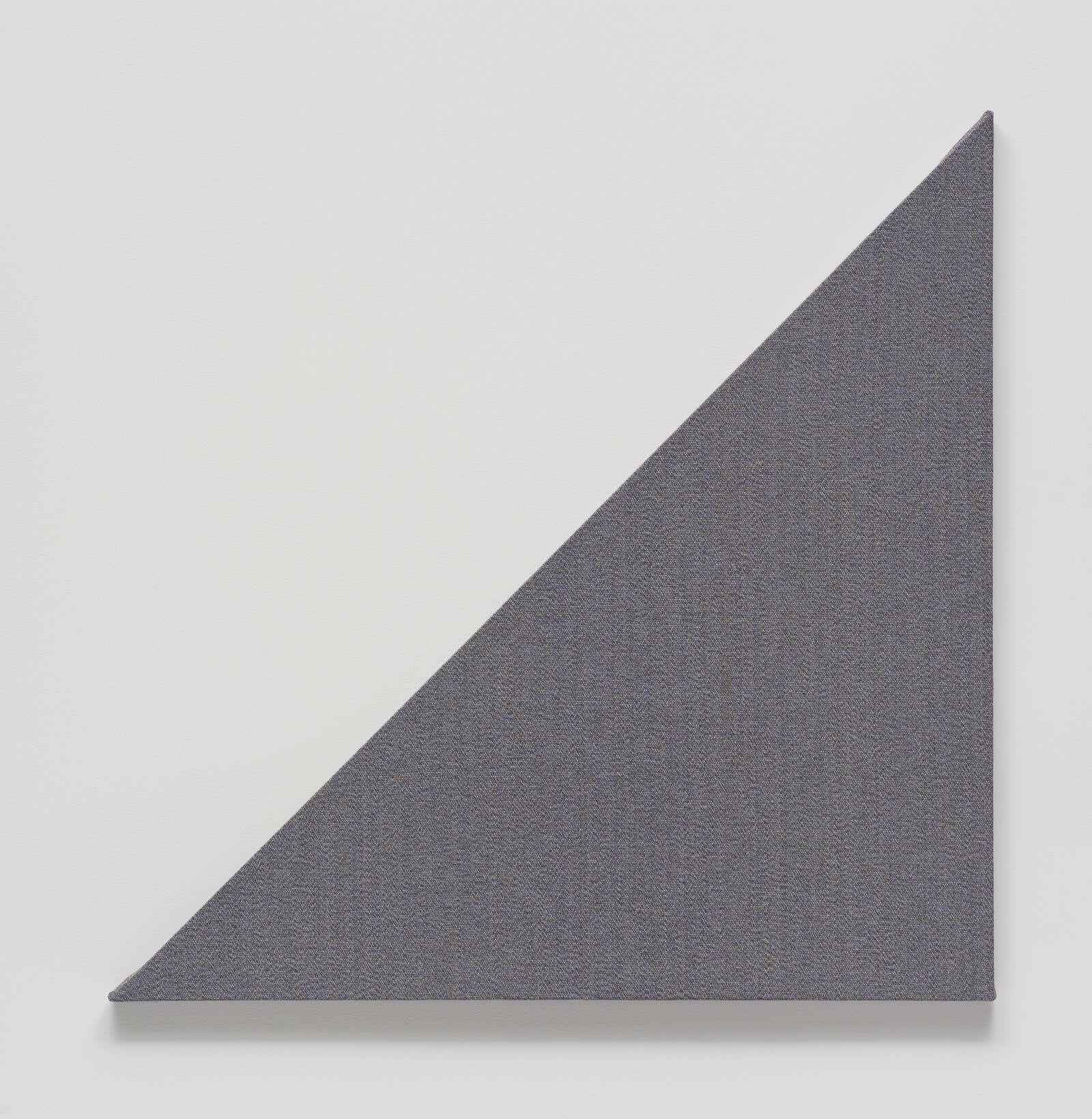

The seven wall works in Willem de Rooij’s new exhibition are each one part of a tangram, a simple Chinese puzzle in which this family of shapes come together to form a rectangle, or one of 6,500 other possible outcomes. First marketed in Germany in the late nineteenth century, they were often carved from stones or imitation earthenware, similar to the color scheme here. Each piece, or tan, is a shape of stretched fabric enlarged to several feet high and wide, spaced generously, and woven from threads dyed the seven colors most prevalent in de Rooij’s oeuvre: black, blue, brown, gold, pink, silver, and yellow, combined in varying concentrations, lending a slightly different shade of brown to each of these works when observed from a distance (Rosa, Dreieck; Gelb, Parallelogram; Schwarz, Quadrat, and so on; all works 2015) while an additional two rectangles (both gemischt groß) are colored by an even distribution of differently pigmented thread in each weaving, leading to two pieces mirroring the exact same muddy brown to each other. An intimate glance at any of them discloses the vibrant prism of each weft, but it has to be so close as to almost softly crush them.

The fabrics were made, like all of de Rooij’s weavings, with Ulla Schünemann in a factory near Potsdam on nearly 300-year-old looms. Starting from the spectrum of Silver to Gold in 2009/2011, they’re now a shimmering bronze. The product they’ve collaborated to make is something like sandpaper—undulating shades of sepia, all texture, no edges. The warm radiance of such simple, flat forms must be borrowed from the Netherlands’ Golden Age of painting by the Dutch, Berlin-based artist, as a disseminated seventeenth-century glaze softens these severe objects. Continuing to practice such historical production, and with such deliberation, elevates the fabric from Minimal materiality to a surface for anthropological representation.

The installation is spined by a sweeping taupe arrangement, intimidating in posture, heartbreaking in its tactile frailty. Bouquet XVI, the city’s memento mori flora offering, made in collaboration with florist Joseph Free, is a grand, ornate corsage almost reaching the ceiling, colored like a sandcastle, and, like many of his “Bouquets,” shows very little color contrast between its ochres and chestnuts in person, virtually none in photographs. XVI is composed of whole preserved local palm-tree fronds and wispy, long-stemmed flowers, each one brittle to the touch. All were sourced from the sidewalks of the Hollywood blocks surrounding the gallery, completely dried out from the relentless California drought and roughly shed, here rustled lovingly like crushed plumes on a dying sparrow. Giving this welcoming piece some weight is a substantial opaque vase balancing on top of a matching plinth, two pieces resembling marble from a distance, but are actually disguised ceramic and wood constructions, speckled with layers of sienna shades of car lacquer to resemble a synthetic, plastic material slickly veneered in true West Coast finish-fetish style.

The mathematician and chess player Sam Loyd wrote his own guide to the enticing game, 1903’s Eighth Book of Tan, introducing the clipped square paradox, in which a perfect square is completed with seven pieces; next to it, a different composition has the same square with one corner cut off. The same pieces are used in the assembly of both. The puzzle amuses by its illusion of a simple proposition, an obvious win almost made too easy. The geometry of “Legal Noses” (the title is another puzzle, an anagram for “Los Angeles”) cuts away at authorship by taking the same course: the role of artist is sliced, cleanly carved, and parceled out to the florist, the weaver, the auto body shop. Each part is extracted one by one, but it is never less than a square.