A nose—the lead character in Nikolai Gogol’s short story “The Nose” from 1836—fashions itself as a decorated civil servant, so esteemed one can hardly question its privileged stature, as such cachet ought to be unquestionably deserved. No two noses are the same, Gogol notes. Some straddle along Nevsky Prospect without raising an eyebrow, or hide inconspicuously inside freshly baked rolls, whereas some, like Pinocchio’s, increase in size with their forgeries. Regardless, all noses have one commonality: they extrude fluids at different cadences. These inflections are the focus of “Rotornariz,” by Von Calhau!, an artist duo from Portugal founded in 2006 by Marta Ângela and João Alves. Von Calhau, !Von Calhau!, or simply Calhau, adapt their name to the singularities of each project, fluctuating within the disciplinary spaces they traverse while reflecting their own interests. Known mostly for their idiosyncratic concerts and performances that combine music and silent 16mm film, presented either autonomously or alongside graphic design and writing, in “Rotornariz” Von Calhau! entangle this varied approach in one bizarre sniffer.

Writing about Gogol’s own nose, Vladimir Nabokov describes how sharp and notoriously delicate it was.1 Gogol’s morbid attraction towards noses was apparent: vivid descriptions of smells, sneezes, and snorting appear repeatedly as narrative elements throughout his literary oeuvre. In “Diary of a Madman” (1835) noses populate the moon, and in Dead Souls (1842) drunken men fight about sawing off each other’s noses. A running leitmotif in Gogol’s work, Nabokov writes, the nose is as generative as it is generated by Gogol’s fascination with this versatile organ. Contrary to the fictional nose of Gogol’s short story, Von Calhau!’s nose is disguised, not as a state official, but as multifarious characters that coalesce in sneezed-on floors, nasal performances, gestures of collaboration, and palindromic drawing.

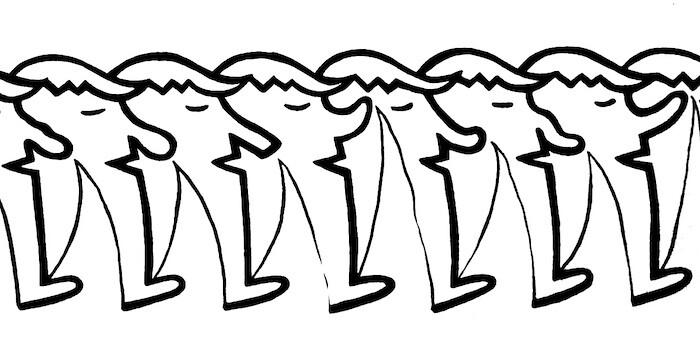

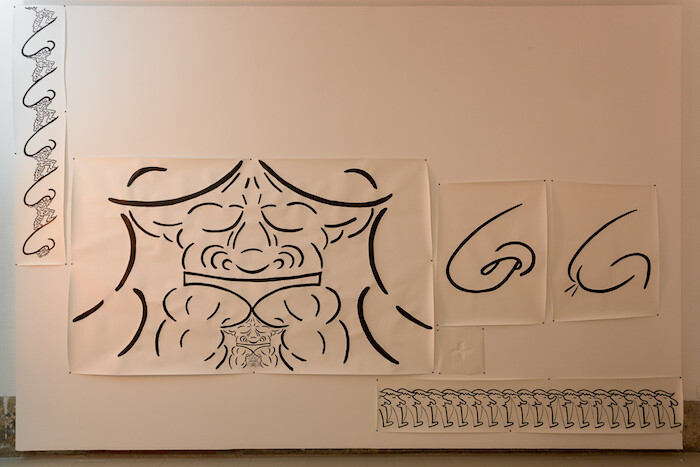

In the gallery space, not one singular reading of the works is immediately legible or audible. A series of unframed, coarsely cut drawings hang with office pins on the wall next to the fractal figure of the master of ceremonies, a smiling pig whose smirk progressively recurs at smaller scales, greeting visitors on the way in, and haunting them beyond the way out (Acid-Porco [Acid-Pig], 2015). The Orwellian swine flags a strange familiarity that is intensified by the constant irruptions of a loud sneeze that does not seem to inhabit any body in sight. Upon close inspection, a smear of liquid on the gallery floor is the only evidence of the blaring noise discharged from the sound installation Espírrito [Ghostly Meager Sneeze], 2016. This vital fluid is the plasmatic substance that coheres the many disciplinary fields in which Von Calhau! operate. The secretion hence becomes as important as the organ that secretes, creating an ambiguous division between the two: the drawing Carregariz [Nose picking] (2016) features a recursive image of a nose carrying itself, which could just as easily be a fractal view of the excretion. For Von Calhau!, the pantomimic nose reads the same backwards as it does forewords: in Ranho Aplnista [Climber Snot] (2016), a viscous figure climbs up a nose, yet the drawing could just as easily show a substance flowing downwards; Incremento Excremento [Increment Excrement] (2016) is a nosedive recto verso. In “Rotornariz,” as in Gogol’s story, the nose is self-governing and wanders about in space (the long, horizontal drawing Piss Walker, 2016, captures a panorama of it cruising), reflecting the strife and colloquy that underlie Von Calhau!’s dialogical practice: Mais Subtraído [Subtracted Addition] (2016), a cut-out of a plus sign, testifies to how poles pull in opposite directions and request inverse movements from the artists.

Perhaps due to an underlying frustration with language and the constraints of description, syntax, and grammar, Von Calhau! appropriate and transform literary devices to render new meanings visible. Autological statements explore the often contradictory nature of language. AEIOU (2016), for example, is a wordplay, drawn on paper, on the puerility of growth. In it, the vowel “e” from the Portuguese word crescimento (meaning “growth”) undergoes procedural alphabetization, foregrounding madeup words, among which “cresciminto” appears as an amalgamation of the root “growth” and the present tense of the verb “to lie,” here in the singular person. Literary devices operate as strongly in this exhibition as within Von Calhau!’s music, performances, posters, and drawings. The latter mark the beginning of any action, wherein palindromes become form and palimpsest becomes method. From here, drawings turn into film, become scores, and convert continuously to the point where they are indexical figures of speech of an all-encompassing practice. In “Rotornariz,” sound, drawings, and a prose poem pitched as handout set the stage for a new film that will premiere in April.

Noses are interlocutionary organs with the world that create sensuous recollections of the times present. A notorious nose like Pinocchio’s lends itself to a paradox: a fabulist who avows his fabrications remains a liar. In a country where financial management still takes precedence in the wake of economic austerity, dignitaries’ noses constantly burst forth and contract—a puzzle Alexander Puschkin also identified when he first published Gogol’s story in the literary magazine Sivreménnik [The Contemporary]. “Rotornariz” is as much a cosmogonic definition of contemporaneity, a snot-like vital gob2: original complex gob system that repeats, re-spits and repulses recursively in eternity.” See Von Calhau!, Oxímoboro (Lisbon: Fundação Geral da Caixa Geral de Depósitos – Culturgest, 2015), 130, author’s own translation.] that inhales interlocution and exhales meta-narratives, as an economical cycle that waxes and wanes. “Rotornariz” is a tale of parsimony that plays on the mundane while letting the trivial act upon it, lending itself to uncanny credibility.

Vladimir Nabokov, “Nikolai Gogol.” In O Nariz (Lisbon: Assírio e Alvim, 2000), 19-20.

“Príncipio originário gosmológico [Sputumlogical Principle