Japan: a land of austere beauty, arcane social ceremony, and indecipherable ritual, or a techno-futurist nation replete with densely populated neon cityscapes. These are the two reductive interpretations that repeatedly color western dispatches from the “land of the rising sun.” While a dichotomy between preservation and progress exists (as it does everywhere), contemporary Japanese culture and society isn’t an unrelenting tug of war between two distinct ways of being. It has risen from a deeper dynamic, a symbiotic and productively antagonistic relationship between what may be termed the traditional and the technological.

“Surface Tension” at White Rainbow gallery, London, uses this dialectic for thematic purposes, bringing together four artists who use traditional craft techniques to produce painting, sculpture, and print that engages with and interrogates contemporary Japanese life. It is a modest exhibition of intricate and at times subtly spectacular art, and it is this latter effect that threatens to push work into decorative territory, as is the case with Masaya Hashimoto’s pieces. Living in a mountain temple for over a decade, his elemental existence has been formalized and romanticized in three intricately detailed flower sculptures made from the bones and antlers of deer, Ayame – Iris Sanguinea (2014), Takagoyuri – Lilium ormosanum (2014), and Amasakisou – Marina blossomnia (2010). Impressive and expertly rendered, they are testaments to Hashimoto’s concentration and skill, but are nevertheless completely cut off from modern life.

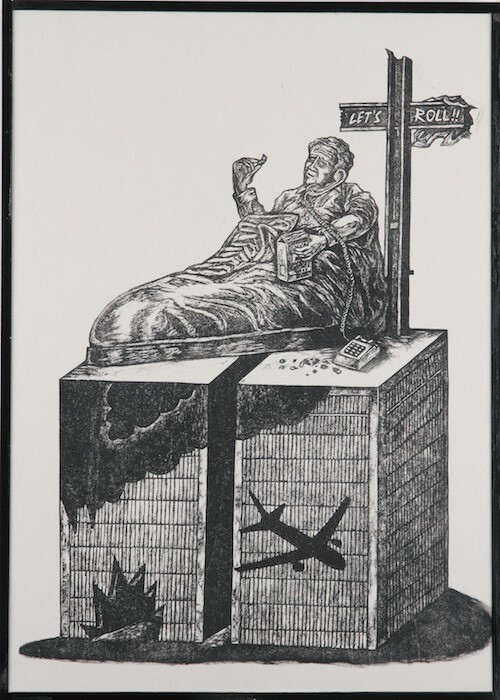

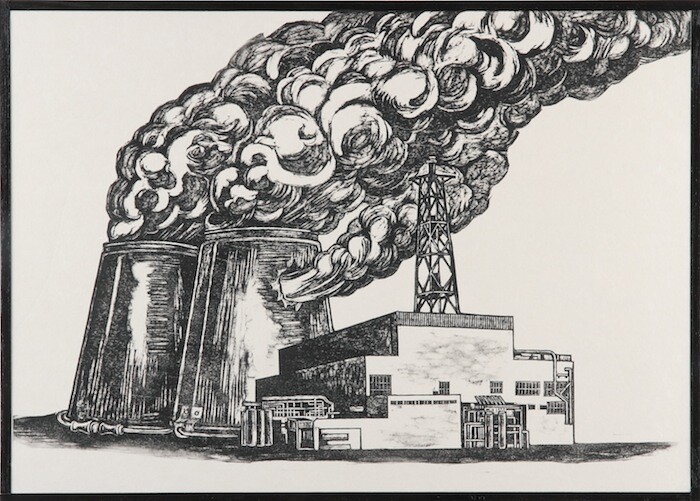

Hashimoto is the exception here, however, and the three remaining artists suffer no such disconnect. Sachiko Kazama’s “HEISEI EXPO 2010” series consists of darkly humorous graphic woodblock prints that document—and satirize—socio-cultural and political events that have so far taken place during the Heisei period (eras in modern Japan are named after and largely correspond to the reigns of emperors; the Heisei period began in 1989 with the start of Emperor Akihito’s rule). Each work compellingly reimagines events as individual, commemorative pavilions in a large-scale exhibition. In My Room Pavilion (all 2010) a hoarder’s bedroom is turned inside out so that the interior, book-lined, and cluttered shelves now form exterior walls. Hometown Revitalisation Pavilion, a garish, postmodern juxtaposition of monuments arranged around a brick wall—a sphinx, a temple, a Buddha—sends up Japanese city administrators’ passion for gimmicky and incongruous architectural projects that are supposed to spearhead regeneration, but ultimately fail—the 158-meter-tall “Play Park Gold Tower” in provincial Utazu-cho, for instance.

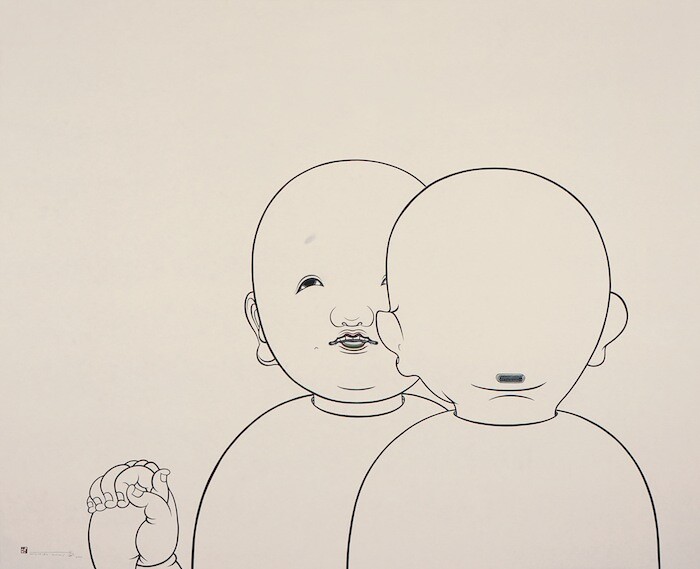

Kumi Machida’s dreamlike paintings—engaging figurative works confidently rendered in smooth deep blue (almost black) outlines—make use of the traditional pairing of sumi ink on kumohada linen paper (a beige surface against which monochrome strokes stand in bold relief). Honeymoon with life (2013), two featureless figures whose conjoined arms form a continuous Mobius strip, is an image of floating, biomorphic surrealism; while Three Persons (2003) actually shows two androgynous bald figures, holding hands, who appear to have HDMI ports in the backs of their heads. Machida’s paintings capture not-quite-human beings paused in an ambient, meditative state of interdependence. They suggest a possible future outcome of genetic engineering and the technological singularity. Perhaps the end product of cyborg technologies and artificial intelligence won’t be super intelligent robots bent on eradicating the human race; perhaps they’ll simply withdraw from society and contemplate each other.

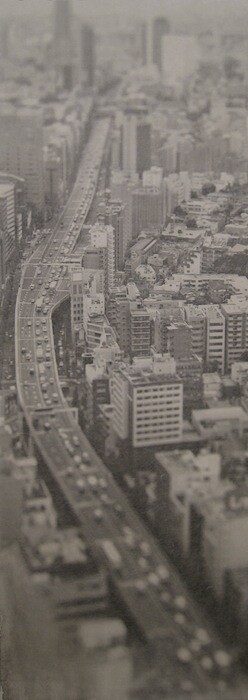

A congested, sepia-tinted Japanese cityscape is split through the middle by an elevated highway carrying heavy traffic. This is Hidenori Yamaguchi’s photorealist ink and brush painting Gentle Milestone (2015), and the artist’s impossibly intricate work produces a trompe l’œil of sorts. What first looks like an old photograph and then a pencil drawing is in fact the product of skills developed while studying in a Chinese university. There the calligraphic discipline of rinsho—making freehand copies of canonical masterpieces—was an integral part of the artist’s training.

With its aged vision of the contemporary urban environment, Yamaguchi’s synthesis of past and present brings the viewer back to familiar territory. This is the Japan we know, a skewed image of the nation as entirely megalopolis, formed in the popular western imagination through views of cities like Tokyo and Kyoto, whose centers are filled with high-rise blocks containing single-room apartments. What we see and hear less of are the single persons, reluctant to marry and procreate, who are increasingly occupying these flats. Look beyond the proverbial time-lapse footage of citizens and salarymen in a Tokyo rush hour, and depopulation is a serious risk. Its effects can be seen in regional areas dubbed “shutter towns,” places that are haemorrhaging younger residents to the big city. Japan also has an aging population—by 2055 people over the age of 65 will make up 40 percent of the citizenry.1 Opening one of the world’s most homogeneous nations to immigration is one solution to the demographic crisis being touted by commentators. In that regard, this exhibition’s mix of traditional techniques and current themes offers a glimpse into a possible future in which Japanese cultural history is interpreted and expressed by immigrant populations who blend it with their own. The fear of cultural dilution and heritage loss spread by Japan’s nationalist voices is a classic right-wing smokescreen. Japan’s traditions will only endure through reuse, reinterpretation, and reapplication. As the work in “Surface Tension” indicates, it is in this way that heritage can become an essential feature of contemporaneity and not a cultural relic within it.

Mariko Oi, “Who will look after Japan’s elderly?” (2015), http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-31901943.