September 9, 2014

The past 10 years have seen an expansion in the recognition of Latin American artists worldwide, as well as a multiplication of the numbers of galleries and art-related events in Brazil, especially in São Paulo. Being so, a survey of the city’s growing number of contemporary art institutions such as galleries, museums, studios, and off-spaces can only be partly representative of the city’s vast landscape of art and culture. But a survey can nonetheless offer another view on the cultural life of Sao Paulo beyond the world’s second oldest biennial (after Venice, and founded in 1951), which has just opened it’s door to the public. While the Bienal is looking for the very contemporary in art today and doesn’t necessarily meet local expectations for its representation of Brazilian art, the city’s current gallery exhibitions present a consolidation of a Brazilian identity through art and its spaces.

At CAIXA Cultural, in the rather dilapidated downtown of São Paulo, French artist Marie Voignier’s film Hinterland (2009) examines Tropical Island, the man-made bathing resort in Krausnick, a bleak and economically depressed region 60 km south of Berlin. Set in a heated dome that looks like a real-life Truman Show, the film deals with the economic exploitation of tropical clichés. Claude Lévi-Strauss also investigated stereotypical descriptions in Tristes Tropiques (1955), his travelogue about the Amazon, which criticized the Western perception of other cultures. Taking this structuralist text as its point of departure, the exhibition “Os Trópicos” (with Olaf Breunning, Christoph Keller, Marie Voignier, and Libidiunga Cardoso) is an invitation for “cheerful self-critique” (1) of the tropical imaginary.

Instituto Tomie Ohtake, located in the chic neighborhood of Pinheiros, presents the extensive exhibition “Histórias Mestiças” [Mestizo Histories], adopting the vocabularies of art history and anthropology to retrace the hybridity of Brazil’s culture over the past five hundred years, close to the terms of the Brazilian historian and literary critic Sérgio Buarque de Holanda. His significant 1936 essay Raízes do Brasil [Roots of Brazil] advocates a Brazilian self-definition beyond the country’s colonial heritage in the face of an interwoven modernity. (2) Rather than providing a critical analysis of a complex problematic, the exhibition’s abundant representation of different cultures in various epochs illustrates a history of ideas of the sociopolitical in art, photography, and handcraft—the history in this show, however, is not narrated linearly, but grouped in thematic clusters. One of the exhibition’s strongest moments occurs in a small cabinet displaying Claudia Andujar’s photos Marcados [Signed] (1983–1984)—the result of a 1970s commission from the Brazilian government, which lead to her involvement in the founding of the Yanomani Park, alongside other activist engagements. This series is combined with the drawings of Taniki Manippi-theiri (Funeral Yanomami, 1976) and the watercolors of Joaquim José de Miranda (A expedição do Tenente-Coronel Afonso Botelho de Souza aos sertões do Tibagi [The expedition of Lieutenant-Colonel Afonso Botelho de Souza to the Tibagi backland] (1771–1773). One hundred and twenty-five years after the proclamation of the Republic of Brazil and its promises of democracy, the modern heritage of both colonialism and, more recently, dictatorship are brutally apparent in these works.

Another attempt to follow the “roots” of modern Brazil occurs in an old warehouse in the secluded neighborhood of Lapa, where the city momentarily gets very tranquil. It consists of Paulo Nazareth’s spacious installation “Che Cherera” (2014) at Mendes Wood DM. À la Arte Povera, Nazareth combines various objects—amongst others, those from his daily life in a neighborhood outside of São Paulo—with those of African and indigenous cultures, creating the impression of a sociedade mestiça [mestizo society], which becomes suddenly current in the space of the exhibition.

The influence of Afro-Brazilian culture is also given currency in the work of the late architect Lina Bo Bardi, whose architecture and designs countered the conventional museological treatment of two- and three-dimensional objects with an almost artistic ease and who, in the late 1960s, helped to establish modern museology in Brazil and elsewhere. Situated in the commercial neighborhood of Faria Lima, the Museu da Casa Brasileira has dedicated a large retrospective of Bo Bardi’s unique exhibition displays in “Ways of showing: the exhibition architecture of Lina Bo Bardi.”

At the Museu da Cidade de São Paulo, artist group Equipe3’s work Pontos de Vista [Points of View] (1973) is actualized in the exhibition “Equipe3: 1973—2014.” In their response to the international call to boycott the 10th São Paulo Biennale (in 1969) due to repression and censorship under Brazil’s military dictatorship, Equipe3’s artists Francisco Iñarra, Lydia Okumura, and Genilson Soares developed a “game of mutual interference,” working across reality and illusion, and individual and collective production. In addition, it is also worth seeing the archival show “Limits of Ambiguity in Equipe3 and Arte/Ação,” at Galeria Jaqueline Martins.

At Sé, a glass of murky water sits on the windowsill with a shiny brass plate. It is engraved with “O Volume Morto” [Death Water], an expression of the problem of water scarcity in São Paulo. In the meantime, a government program has decreed the importance of saving water and hands out fines for its waste. The delicate, post-conceptual gesture from artist Raphael RG stands within the tradition of Latin American conceptual art. At Phosphorus, in the same building, “The Interview Room” features the work of Fancy Violence, an alter-ego of artist Rodolpho Parigi. Under this pseudonym, the otherwise successful, young studio painter is afforded a performative existence outside of the glamor and gloom of the art market and a temporary position in a subcultural world of cross-dressing and queerness. How this generation of younger artists might challenge contemporary art and its legacies in the face of society’s present transformation remains open ad interim.

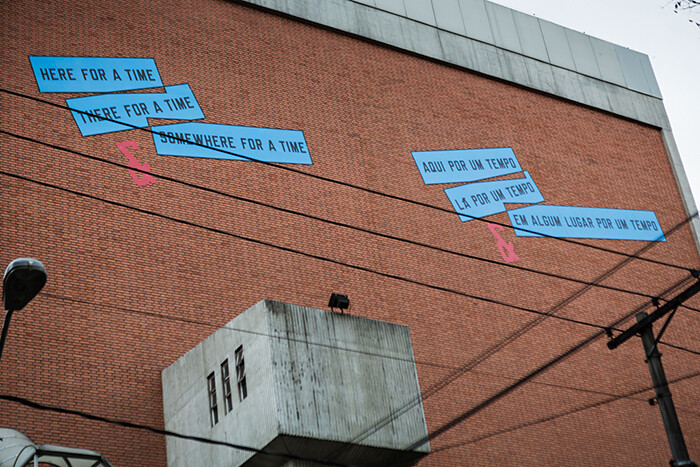

In the meanwhile, and in parallel to these various moments of cultural introspection, the city offers a vast choice of shows of major international figures, including the work of a good sum of canonic conceptual artists: Cildo Meireles (at Galeria Luisa Strina and, with Mario Garcia Torres, at Pivô), Tunga (at Mendes Wood DM), and Paulo Bruscky (at Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo and at Galeria Nara Roesler), who have not only found their place in art history but also in the art market. Despite the big names these exhibitions manage to show their lesser known side, such as Bruscky’s artists’ books and films, or Meireles’s paintings. Meanwhile, Lawrence Weiner’s easily recognizable murals look surprisingly contemporary. On four building façades and on the sidewalk between Luisa Strina and Mendes Wood DM, they appear colorful and quite exotic. Law forbids advertising in the city of São Paulo, so these wall paintings stand almost alone in their rough urban surroundings. His messages seem to echo the worries of the various generations of Brazilian artists, attesting questions that are shared globally. In the streets of São Paulo, fat big letters read “HERE FOR A TIME, THERE FOR A TIME, SOMEWHERE FOR A TIME.”

1) See Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, The gay science, 1882 (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2008).

2) See Sebastian Conrad, Shalini Randeria (eds.), Jenseits des Eurozentrismus: Postkoloniale Perspektiven in den Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2002).