Launch of e-flux journal issues 134–136

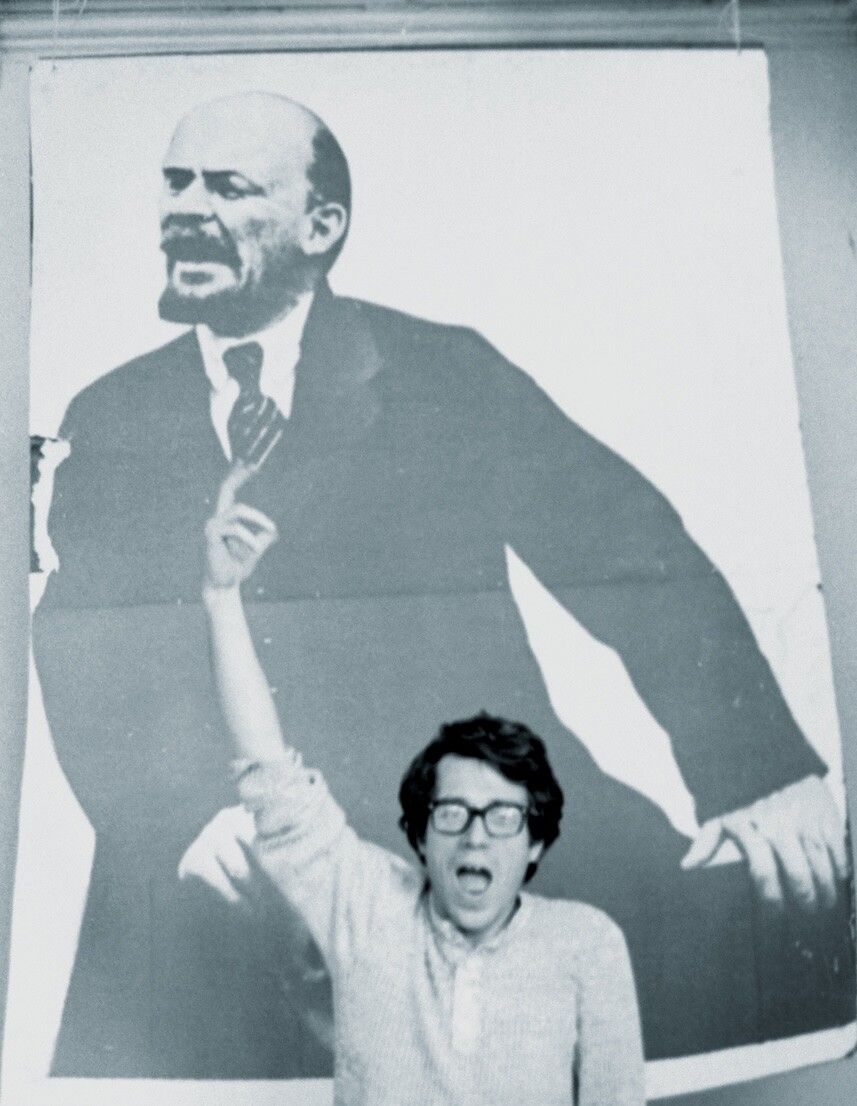

Art history has failed to competently account for the “post-socialist” in postmodernism, not so much as an interpretative framework but as a preexisting and indeed “haunting” condition. The hauntological dimension of post-socialist legacies might just be the missing link that allows us to understand much of postmodern art truly on its own terms, taking account of the inherent contradictions, mediations, and transformations of historical circumstances.

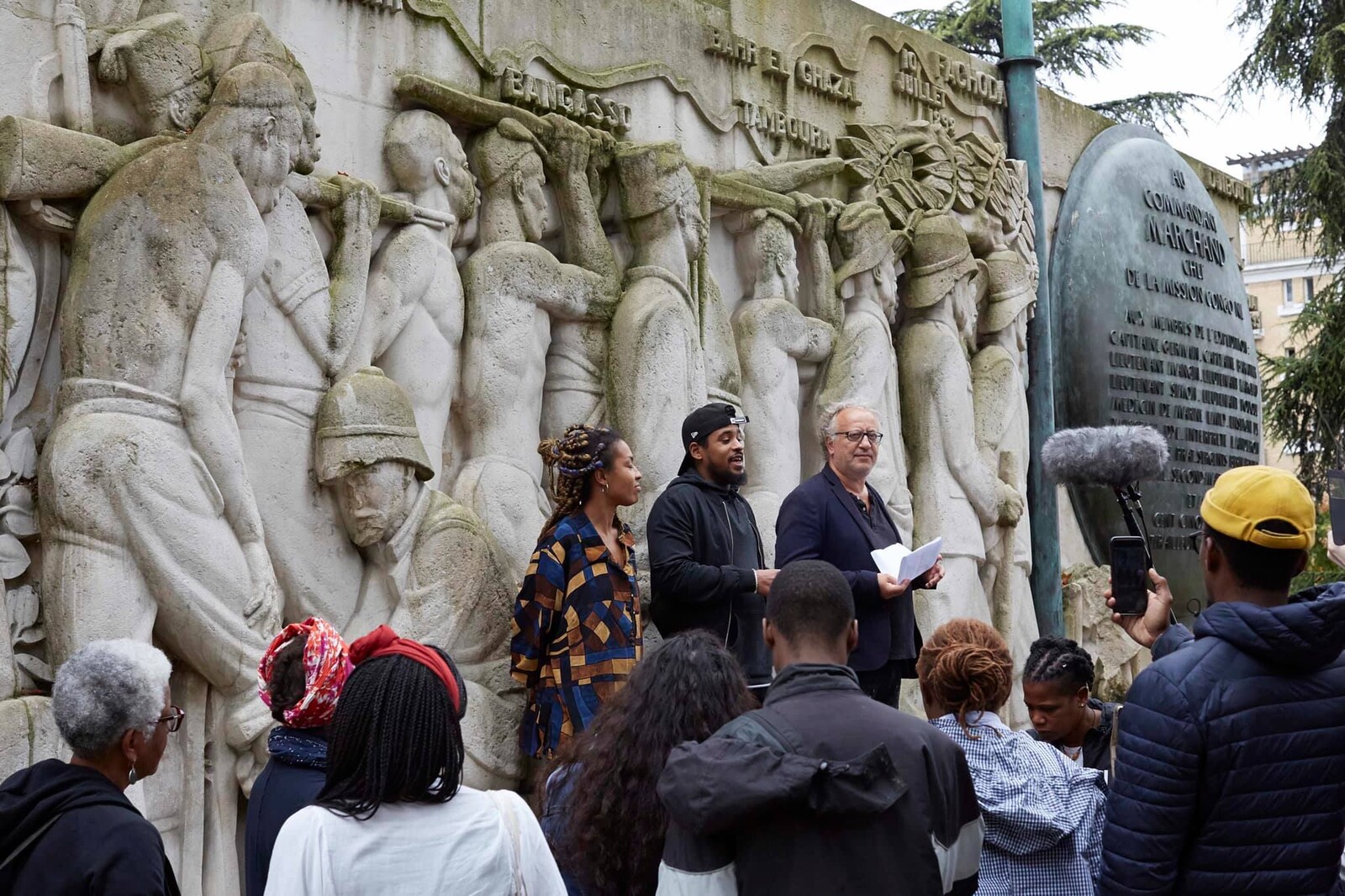

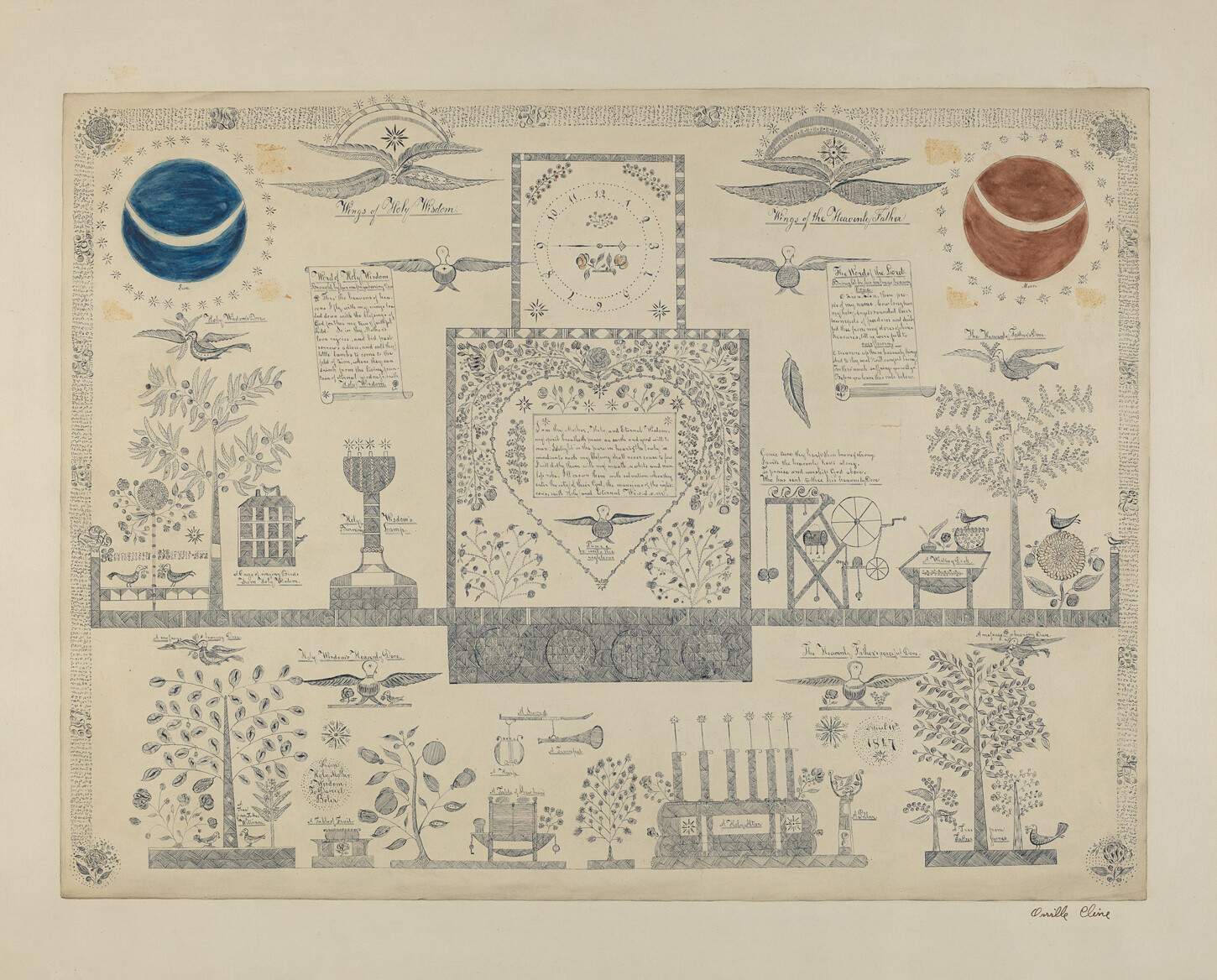

Caste slavery was legitimized through myths, and “justified” through spiritual means. Over the long span of thousands of years, such myths have been compromised and appropriated through many more stories. This is what we Dalits mean when we refer to the oppressive environment long upheld through Brahmanic knowledge production.

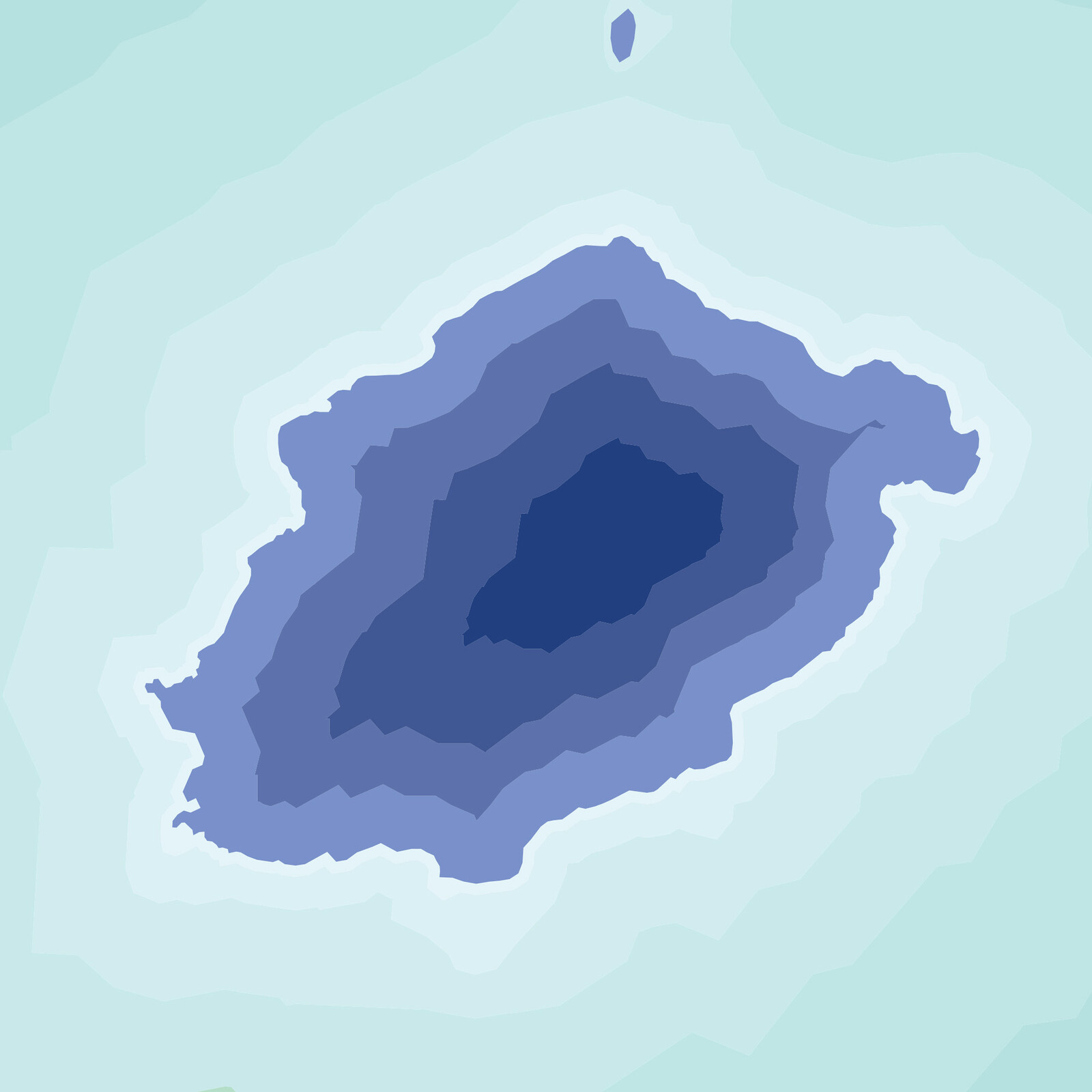

Earth

To grapple with land and its histories is to rediscover life as a weapon. Only a weapon so total is powerful enough to combat the combined spiritual and ecological devastation of our time.

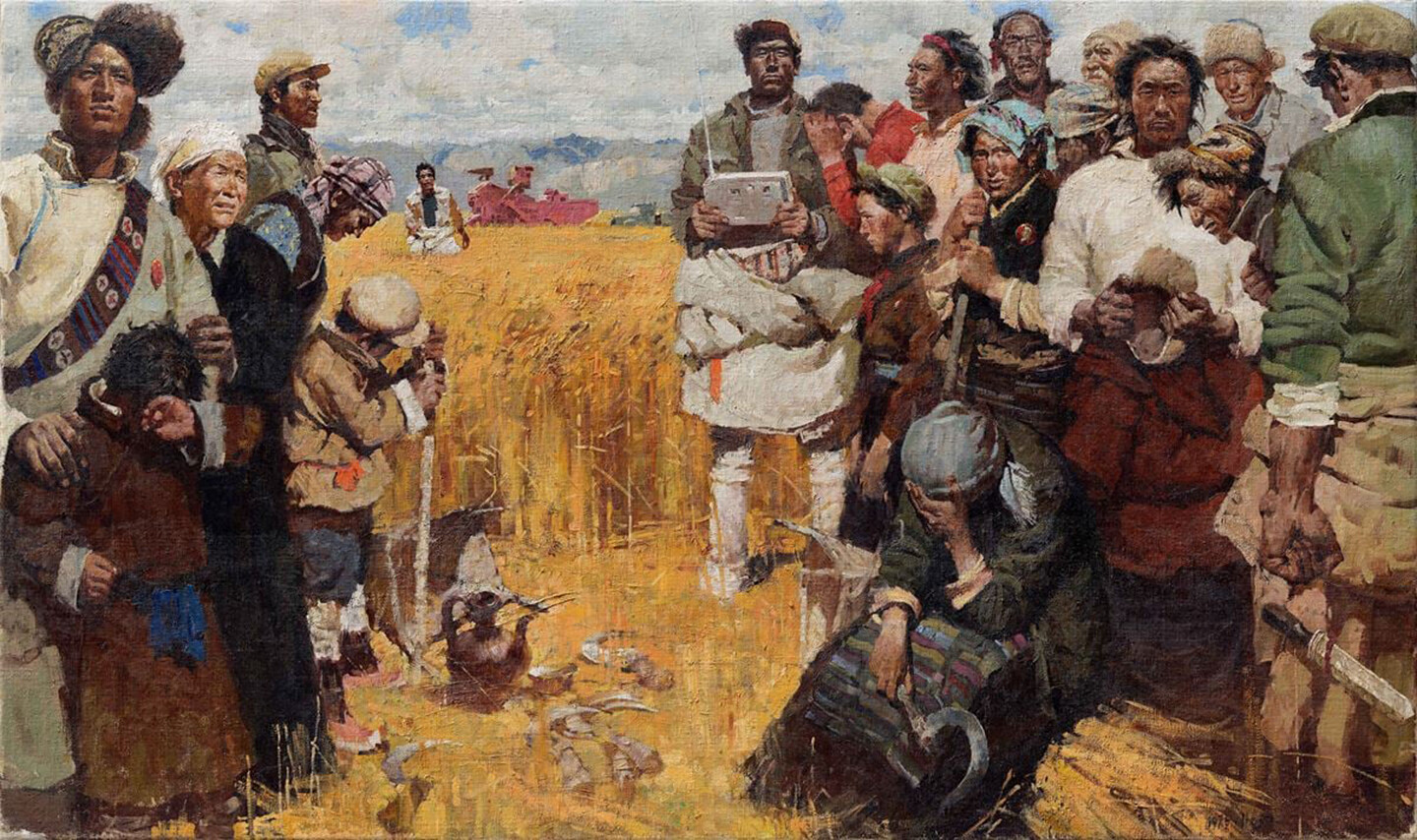

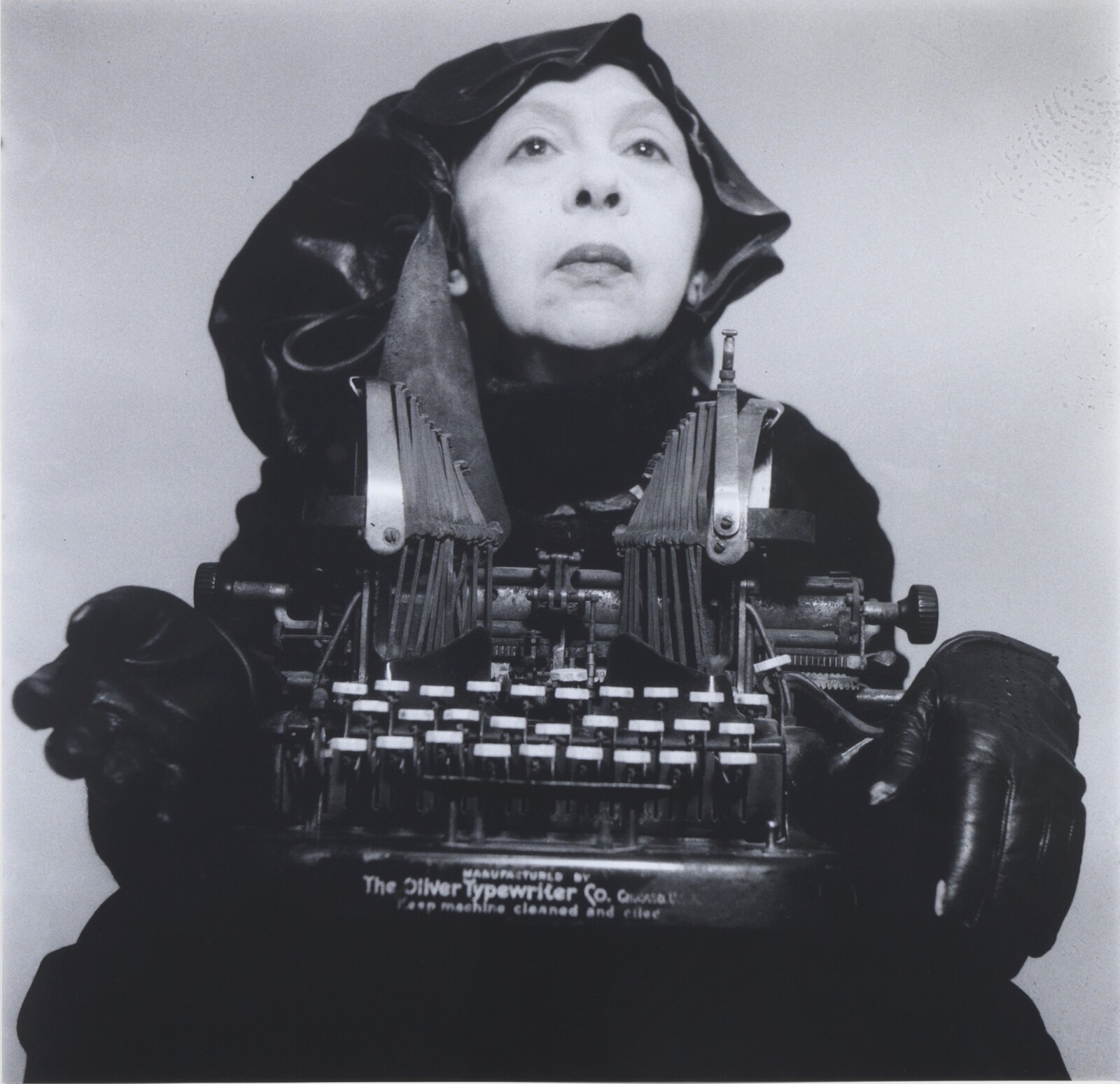

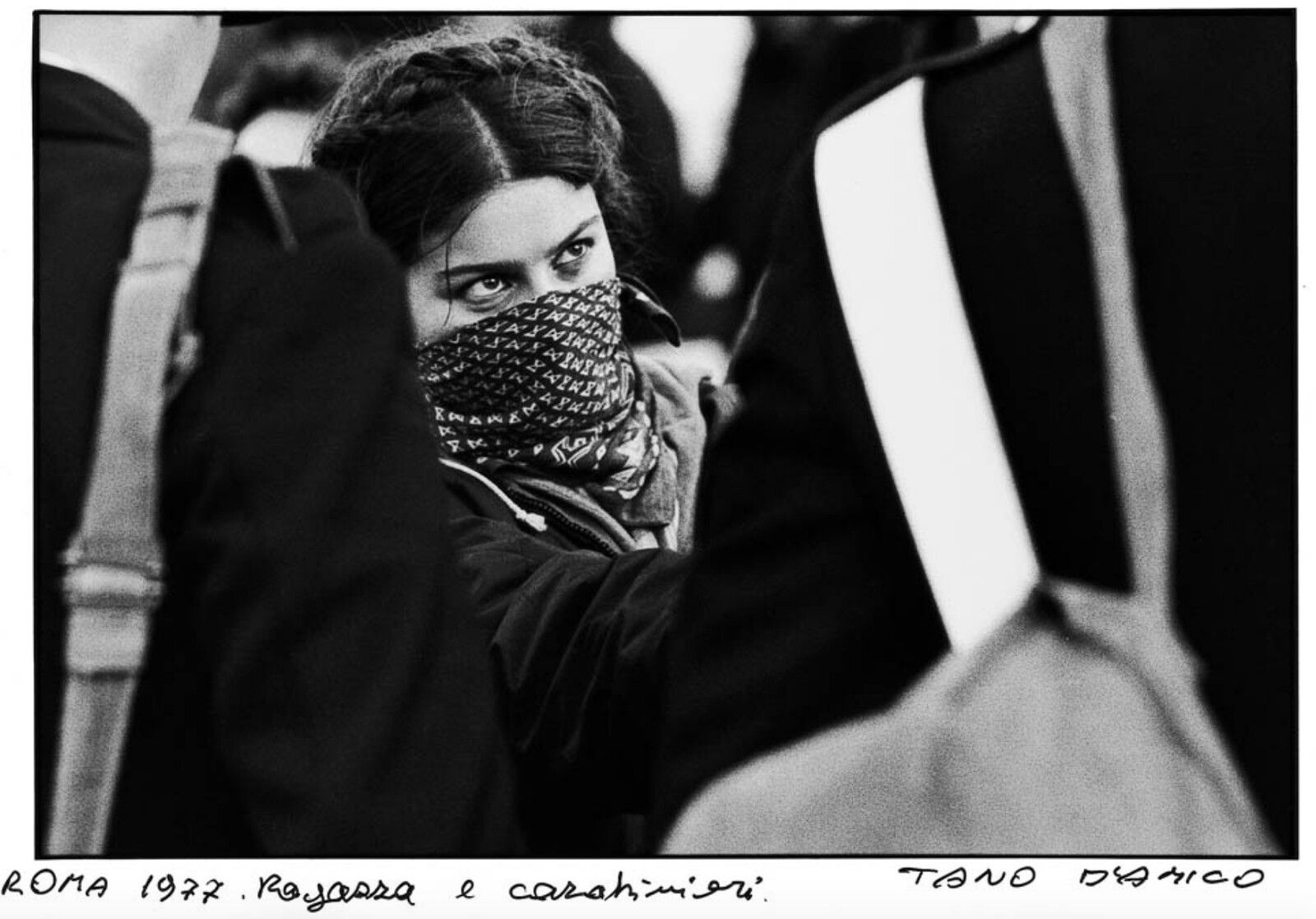

So much was written in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries about methods of capturing time: the photograph entombing Muybridge’s horse mid-gallop, atomic bombs imprinting everything in their radioactive waves as shadows of an instant, the assembly line and the making of the working day, the expropriation of labor power and its metabolization into exchange value. Unlike these violent processes central to colonial and capitalist modernity, and contrary to Sicily’s depiction in mafia tele-series or the mocking tones of journalists from the North, Etna’s lapilli snow and its language are gentler methods of capturing an instant or a series of instants. Perhaps they even constitute a way of communizing time.

Decades of capitalist propaganda has reduced the notion of collectivization to Stalinist terror. This flattening of the term dismisses the breadth of forms that collectivization can take: from nationalizing communal resources and production, to other-than-human redistribution efforts to establish comradely ecologies. It is therefore essential to explore the collectivized imaginaries and practices—collectivizations, in the plural—that make egalitarian forms of life imaginable and actionable.

It seems as if the desire to cancel out the experience of communism over the last decades may have proceeded, step by step, with the desire to cancel out the experience of love. Just as communism has been replaced by an infinite, inconclusive negotiation over rights, so too love has become a contractual affair, an engagement to barter about as if it were any other aspect of existence. Love no longer even has any experience of the end: one is fired, perhaps with an SMS, and if it’s worth the trouble you can put it on your CV.

The order of libidinal agriculture is the order of neoliberal totalitarianism in disguise. The couple form may look like a plot of land for individual use. But really it is an industrial production site for all sorts of capital (financial, cultural, social, emotional, etc.).

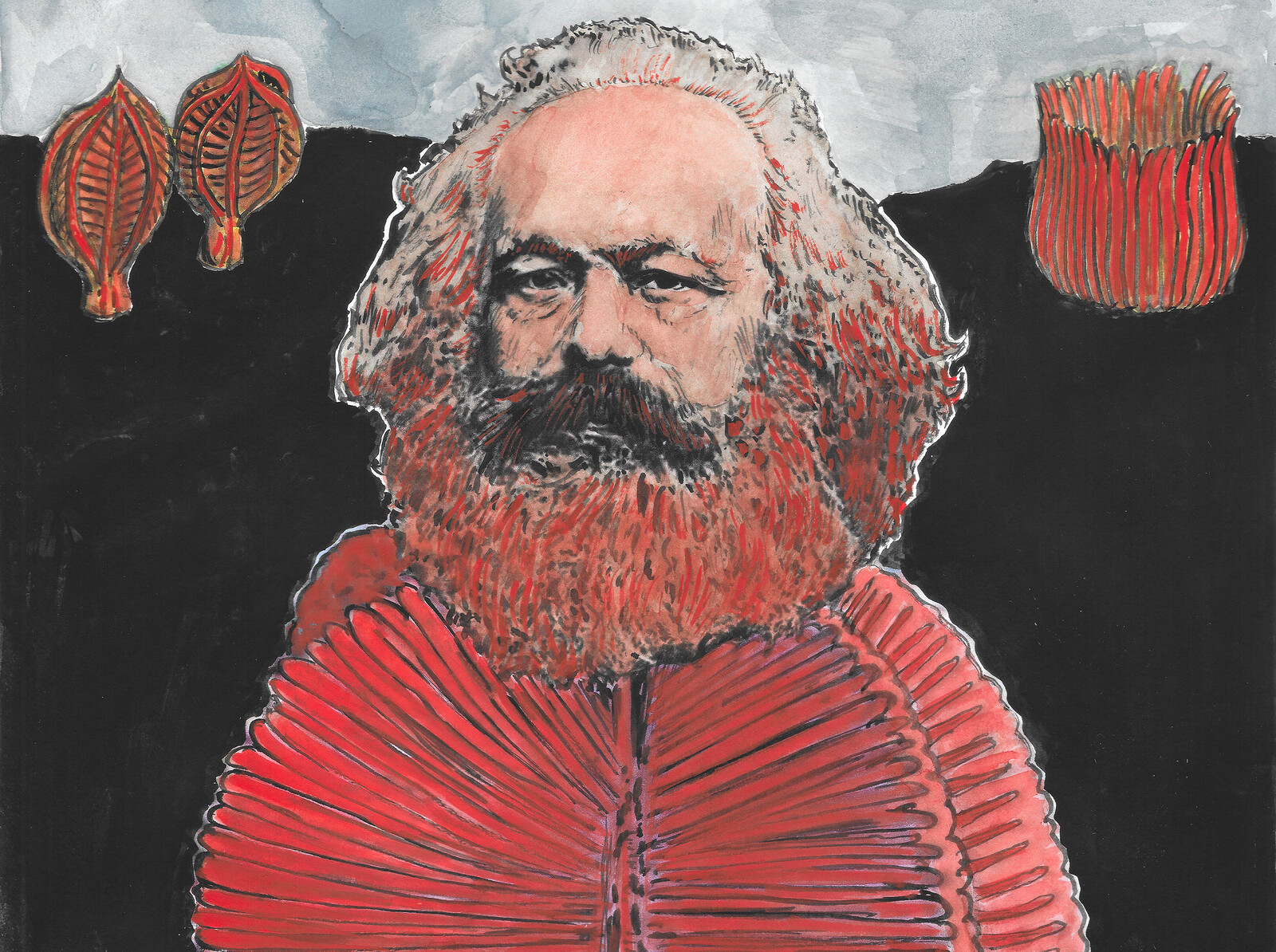

The discourse of Marxism, on the contrary, produces not trust but distrust. Marxism is basically a critique of ideology. Marxism looks not for a “reality” to which a particular discourse allegedly refers but to the interests of the speakers who produce this discourse—primarily class interests. Here the main question is not what is said but why it is said.

You or I, in other words, singly or as a collective, might at some point or another be called to doula the inaugural emergence, or terminal shutdown, of someone’s body. You never know when an extra hand might be required on the occasion of someone’s expulsion of a fetus (dead or living) from their uterus. You never know when your simple watchful presence might be called for because someone is dying and because, without you there, they would be utterly alone. As Madeline Lane-McKinley says, “if we must mother our friends, let us all be mothered.”