What would it mean to position the autonomy of art and art institutions in alignment with, rather than in opposition to, autonomous politics? What would it mean to take seriously Castoriadis’s notion that art only exists by questioning meaning as it is each time established, and by creating other forms for it? What would it mean to extend that to the meaning and mutability of art institutions, the places where art is made, distributed, and received? Here again, autonomy is not about separation or non-relation, but about the capacity to transform.

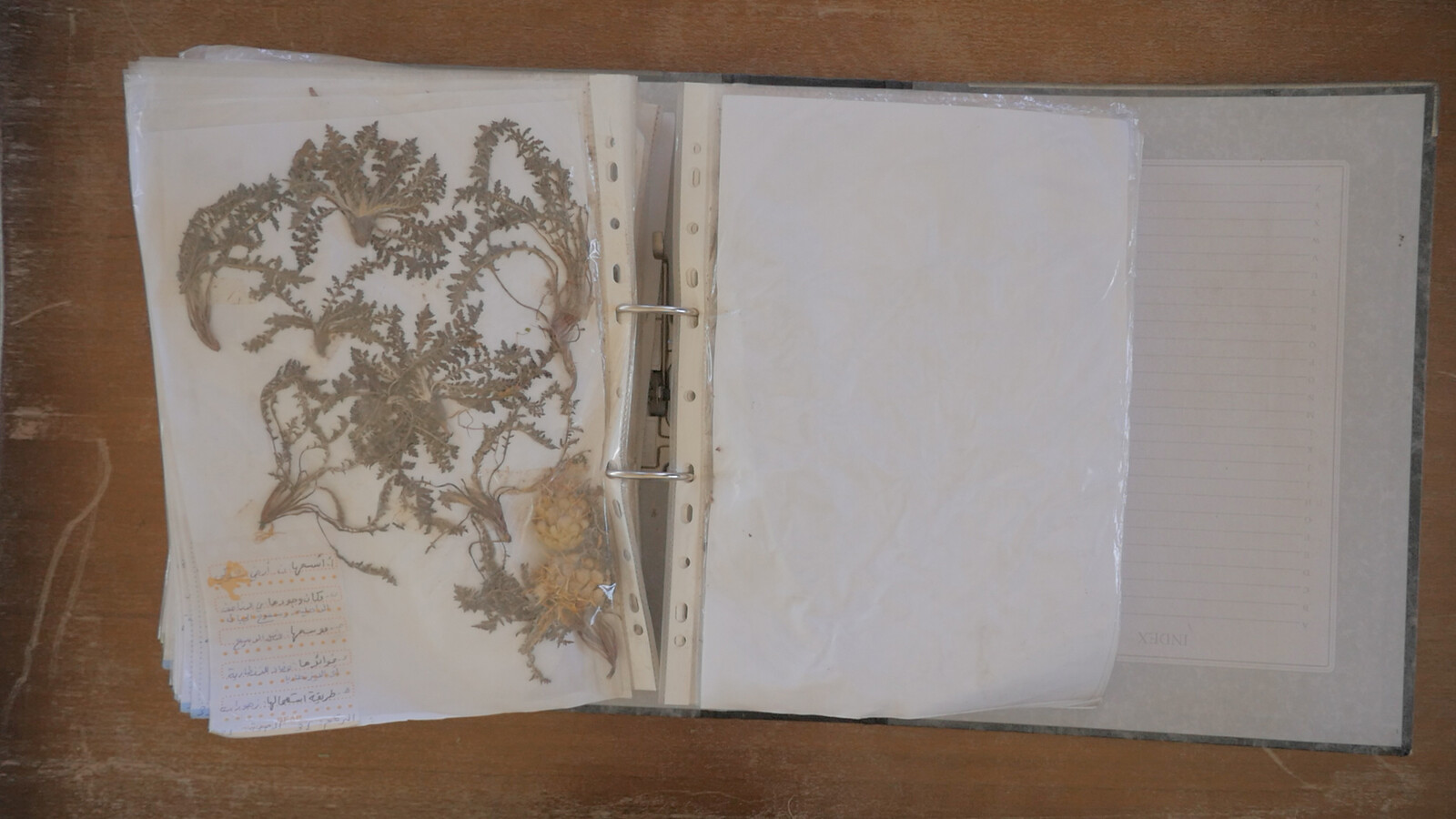

To grapple with land and its histories is to rediscover life as a weapon. Only a weapon so total is powerful enough to combat the combined spiritual and ecological devastation of our time.

Mahalla Stories

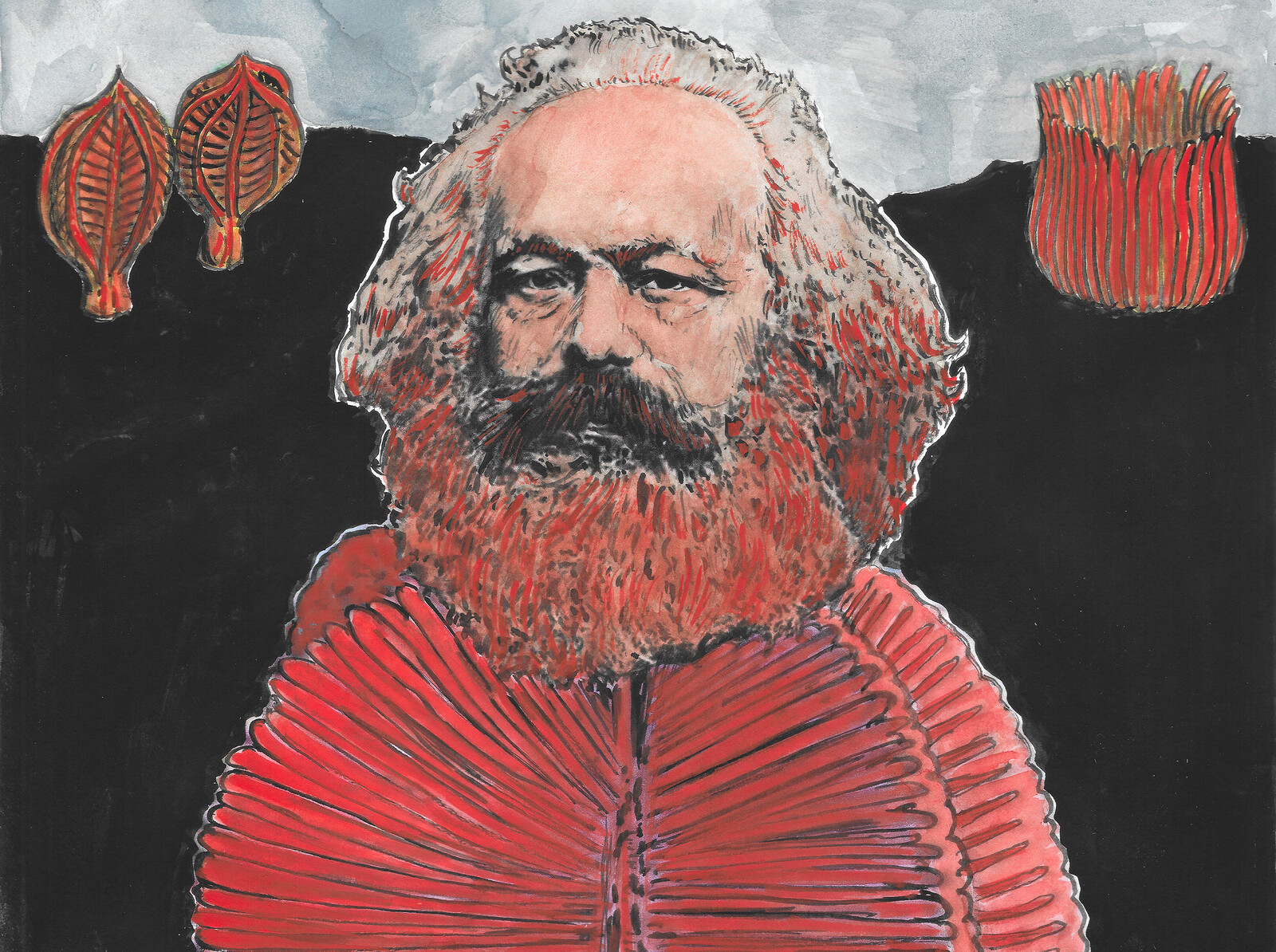

Decades of capitalist propaganda has reduced the notion of collectivization to Stalinist terror. This flattening of the term dismisses the breadth of forms that collectivization can take: from nationalizing communal resources and production, to other-than-human redistribution efforts to establish comradely ecologies. It is therefore essential to explore the collectivized imaginaries and practices—collectivizations, in the plural—that make egalitarian forms of life imaginable and actionable.

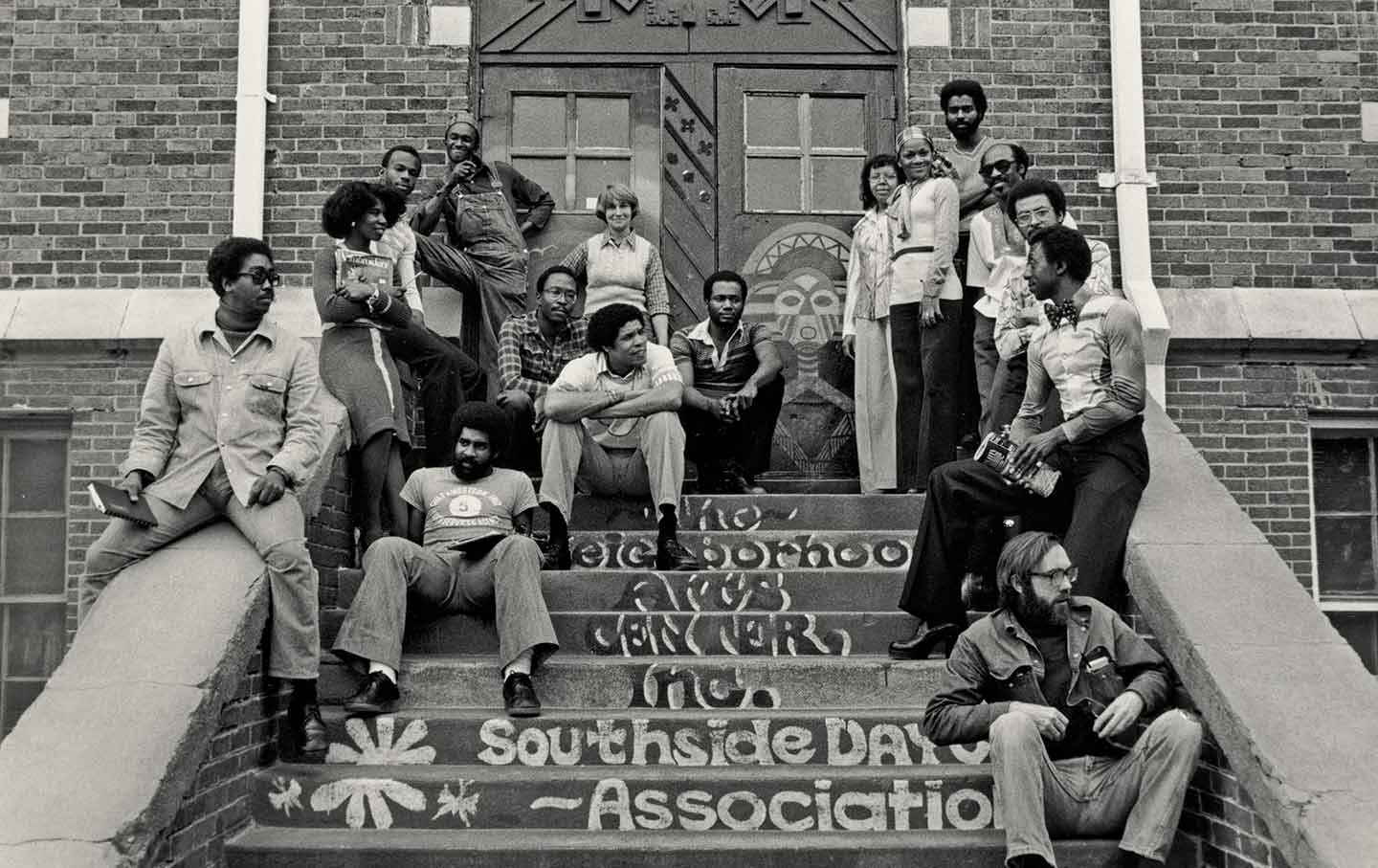

We are drawing on ideas that bring people together in conversation rather than force them into authoritative processes. Conversations meander, and decisions spring forth. We reduce individual control and ownership. We share power and authority, as well as respecting silence and absence. Ideas emerge organically without clear intellectual ownership. It is a collage: thousands of pieces of ideas come together. Bad ideas are polished up with a little collective imagination.

If any illusions remain that only humans have world-making agency in our ecosystem, the consequences of the racial Capitalocene are forcing these to an end. The Capitalocene’s trajectory was to establish “capitalism as world-ecology,” but the truth is that the brutal realities of its extractivist industries have enabled various parts of our violated ecologies to strike back: by hurricane and earthquake, by plastic flood and toxic fire. And now, the coronavirus pandemic predictably makes visible how structural inequalities are accelerated through what is still a relatively containable crisis, and this tells us much about what to expect from the current world order when faced with vastly more aggressive climate catastrophe–fueled pandemics, failed harvests, and millions of climate refugees.

Gender essentialism—“women’s empowerment”—overtakes any class or race discourses, which are at the core of internationalist feminist politics. “Global womanhood” becomes a category or a class in itself. Hunger is separated from class and from the failure of states to provide and distribute wealth equally. The main political aim becomes fighting hunger, without any reflection on what has caused this hunger—for example, the failure to subsidize farmers’ material needs; the historical mismanagement of water distribution, which has led to drought in many areas; the overexploitation of underground water (like in the Bekaa valley); the distribution or subsidization of fertilizers for farmers, which over many years has damaged the soil; toxic waste polluting the water; and more generally the laws around property or land ownership, which favor the few at the expense of the many. NGOs do not address this mismanagement at the state level; instead, they try to compensate for it.