Book launch: Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Routes/Worlds

Elizabeth Povinelli’s anthropology of the otherwise locates itself within forms of life that run counter to dominant modes of being under late settler liberalism.

The tsunami of colonialism was not seen as affecting humanity, but only these specific people. They were specific—what happened to them may have been necessary, regrettable, intentional, accidental—but it is always them. It is only when these ancestral histories became present for some, for those who had long benefited from the dispossession of other people’s labor, thought, and lands, that suddenly the problem is all of us, as human catastrophe. The phrase “all of us” is heard only after some of us feel the effects of these actions, experience the specific toxicities within which they have entangled the world. Let’s not have critical oceanic studies be taken by this con—not have an oceanic feeling be that which annihilates the specificity of how entanglements produce difference in order to erase the specific ancestral present.

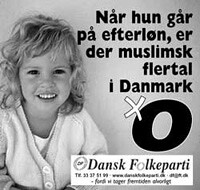

In the landscape that is gradually emerging, it’s not so fantastical to imagine the eventual replacement of all international exhibitions with beer festivals, local food and craft fairs, or other types of events that reaffirm a particular identity and sense of belonging, rather than offering an encounter with something or someone outside of that tightly constructed place. It’s also becoming possible to imagine a reduction or even a termination of human movement: from the reemergence and fortification of numerous national borders, to increasing visa restrictions and the exclusion of entire religions or nationalities from entering certain countries, to perhaps requiring a permit to leave. I grew up in the Soviet Union and I do remember living in a regime under which you can’t leave the country without permission from the state.

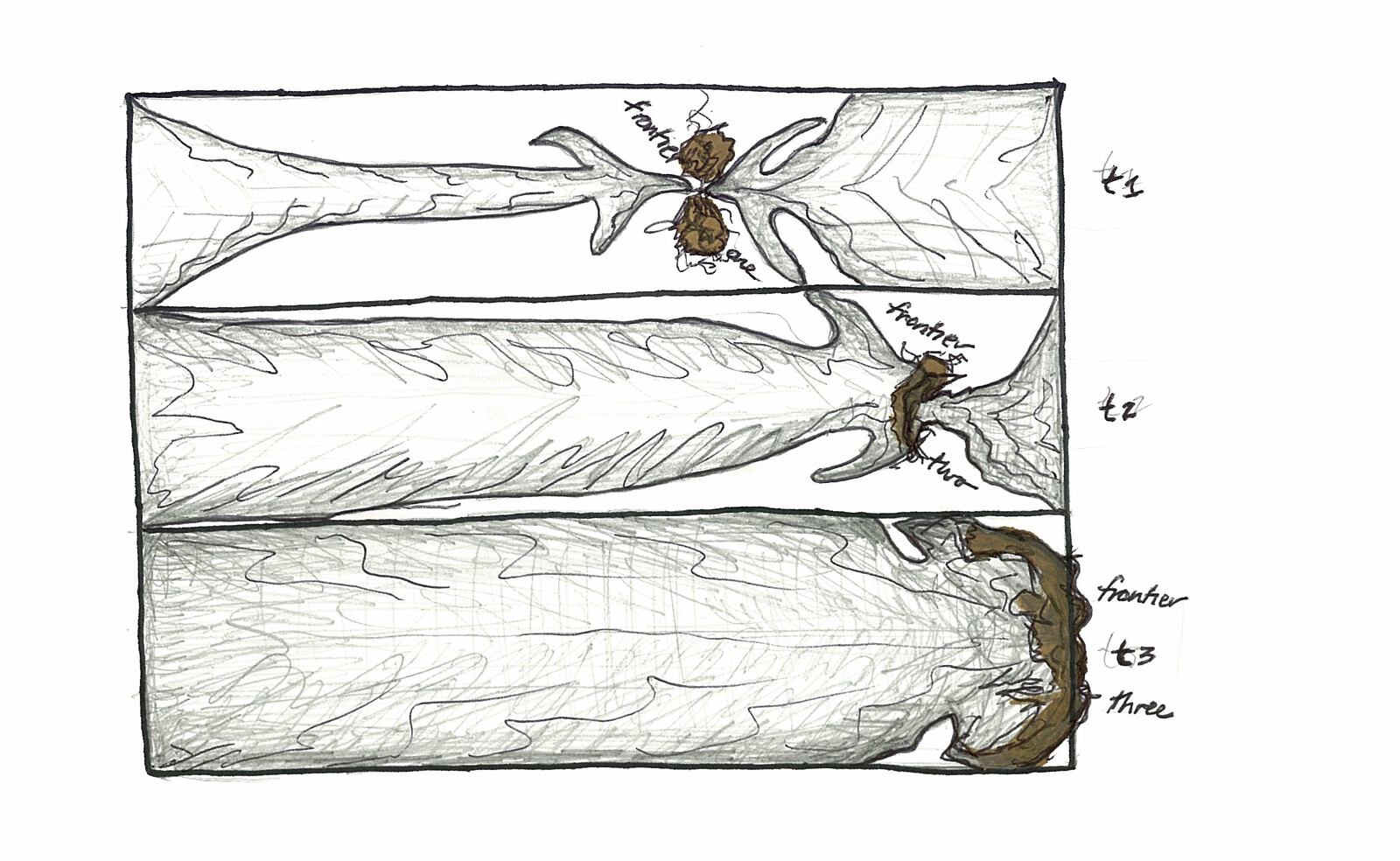

Two imaginaries of space have played a crucial role in the emergence of liberalism and its diasporic imperial and colonial forms, and have grounded its disavowal of its own ongoing violence. On the one hand is the horizon and on the other is the frontier. These two spatial imaginaries have provided the conditions in which liberalism—in both its emergent form and its contemporary late form—has dodged accusations that its truth is best understood from a long history and ongoing set of violent extractions, abandonments, and erasures of other forms of existence, and have enabled liberalism to deny what it must eventually accept as its own violence.

The Desert does not refer in any literal way to the ecosystem that, for lack of water, is hostile to life. The Desert is the affect that motivates the search for other instances of life in the universe and technologies for seeding planets with life; it colors the contemporary imaginary of North African oil fields; and it drives the fear that all places will soon be nothing more than the setting within a Mad Max movie. The Desert is also glimpsed in both the geological category of the fossil insofar as we consider fossils to have once been charged with life, to have lost that life, but as a form of fuel can provide the conditions for a specific form of life—contemporary, hypermodern, informationalized capital—and a new form of mass death and utter extinction; and in the calls for a capital or technological fix to anthropogenic climate change.

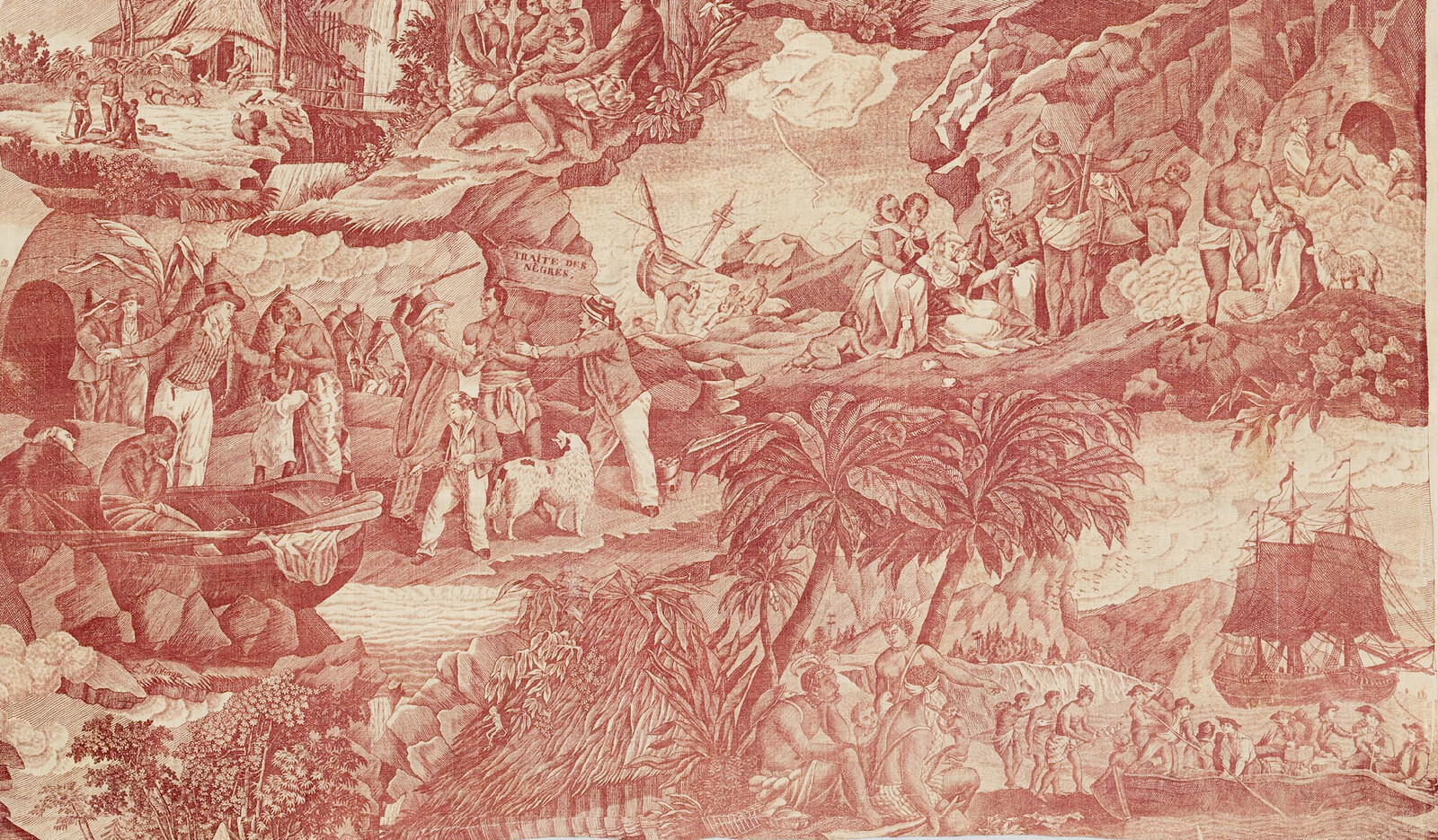

The plantation regime and, later, the colonial regime presented a problem by making race a principle of the exercise of power, a rule of sociability, and a mechanism for training people in behaviors aimed at the growth of economic profitability. Modern ideas of liberty, equality, and democracy are, from this point of view, historically inseparable from the reality of slavery. It was in the Caribbean, specifically on the small island of Barbados, that the reality took shape for the first time before spreading to the English colonies of North America. There, racial domination would survive almost all historical moments: the revolution in the eighteenth century, the Civil War and Reconstruction in the nineteenth, and even the great struggles for civil rights a century later. Revolution carried out in the name of liberty and equality accommodated itself quite well to the practice of slavery and racial segregation.