Emilija Škarnulytė: World and Its Models

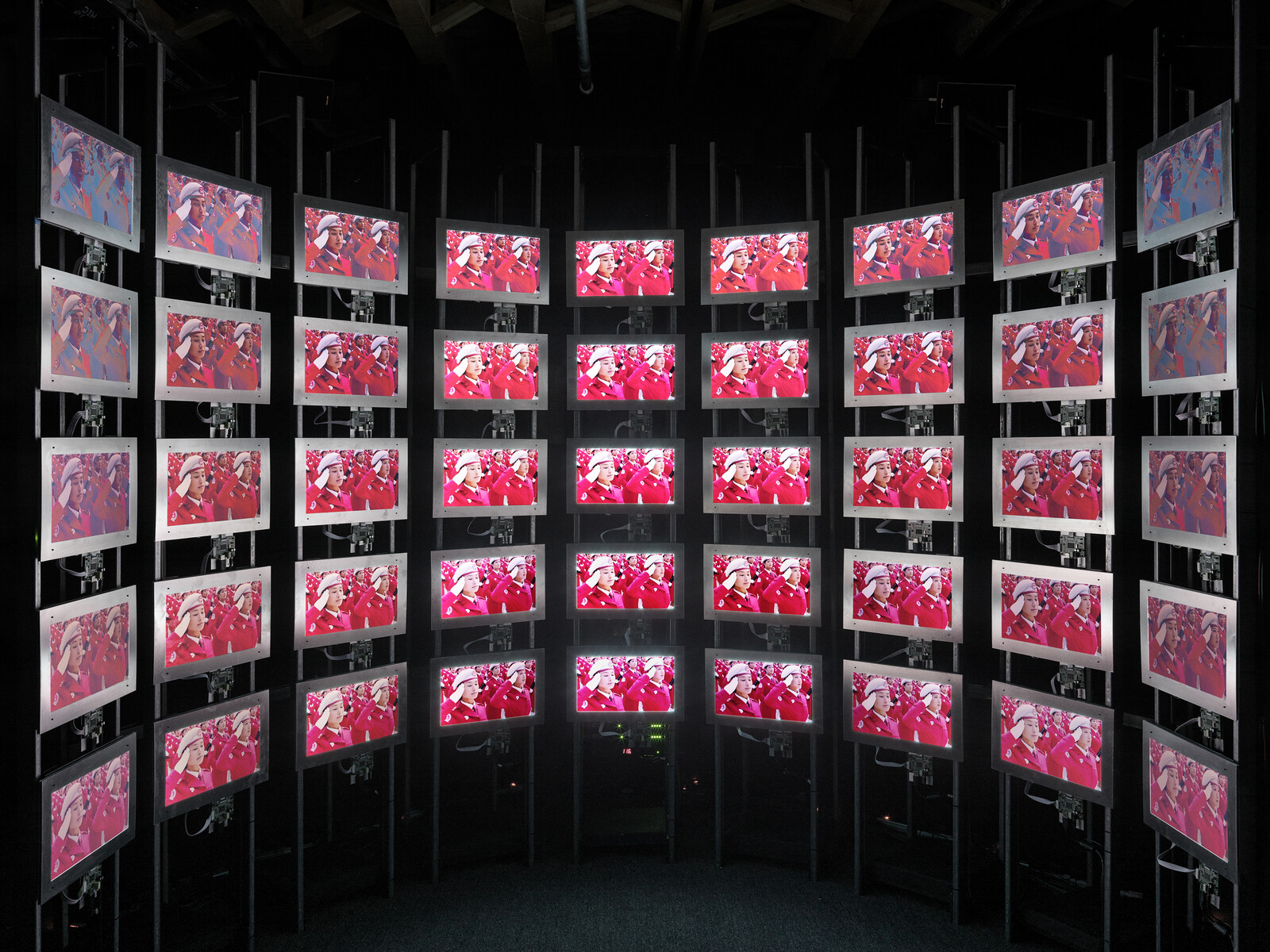

We are often reminded today that “empires do not know their borders.” This speaks of ultimate uncertainty, and thus of the imperial urge for conquest, which is driven by paranoiac imperial certainty about a threatening outside. The Russian Federation claimed that they “had no choice” but to invade Ukraine and kill its people, which constitutes a complex and contradictory epistemological landscape that could probably only be deciphered through psychoanalysis.

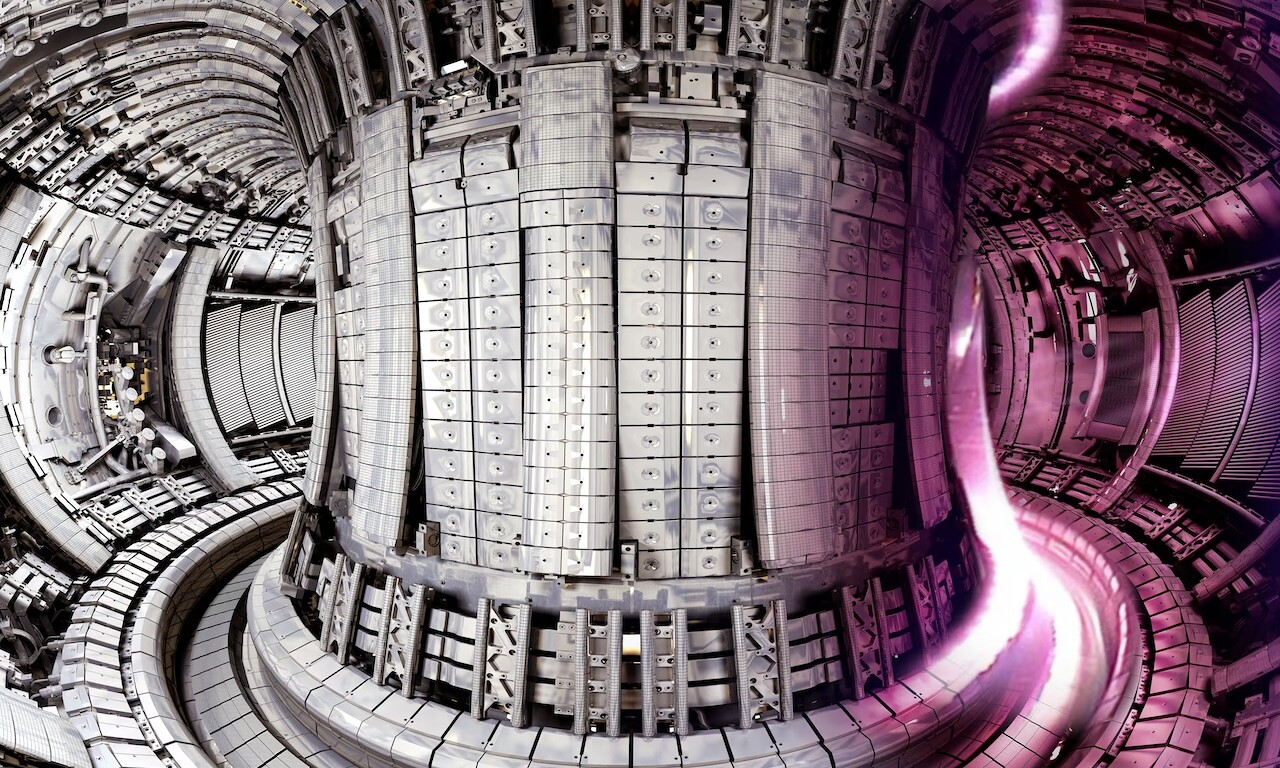

A premediated and unlawful act of terrorism committed either by rebels or governments can be isolated, but it can also take place in the context of war. In this case, it should be distinguished as such. Russian forces, it seems by now, were better prepared for a parade than combat. They intended to achieve victory in their failed blitzkrieg by a series of distributed terrorist acts. Their attacks on “not just selected but also random targets” were meant to seize attention and paralyze the country by shock, horror, fear, or revulsion. The occupation of a nuclear power plant—one such terrorist act—equally targets local and remote publics, opening multiple channels of negotiation or pressure to compensate for the Russian military’s disorganized invasion.

Given that the war is inexplicable in strategic terms, to understand the war we don’t need to think geopolitically, but rather psycho-pathologically. Perhaps we need a geopolitics of psychotic outbursts.