Mabel O. Wilson, “On the Violence of Architecture”

Shana Moulton: In Search of Meaning

Part Three

Screening: On trash collectors and Michael Jackson impersonators

Forms of Experience: An Evening with Su Friedrich

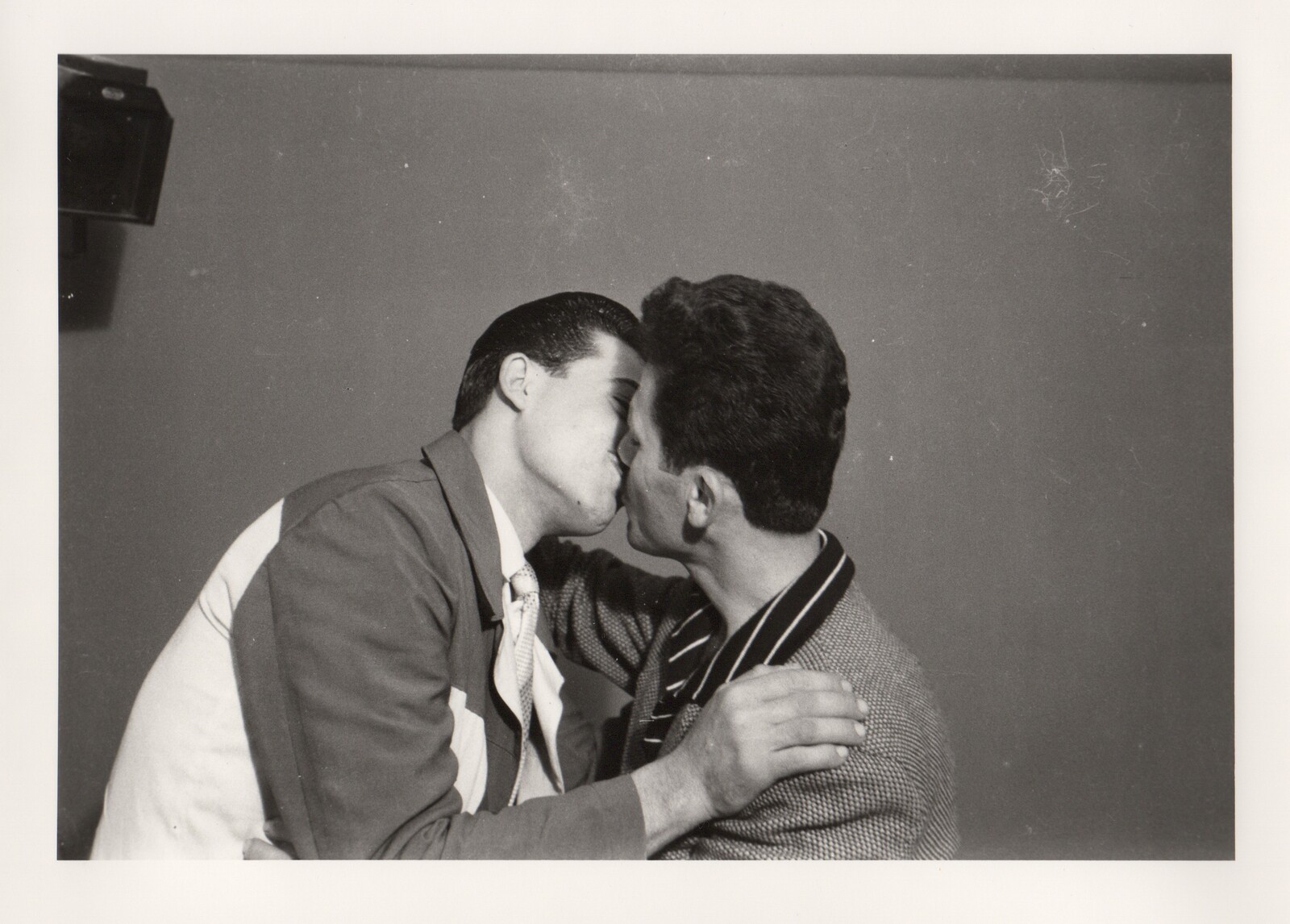

Blind Ambition

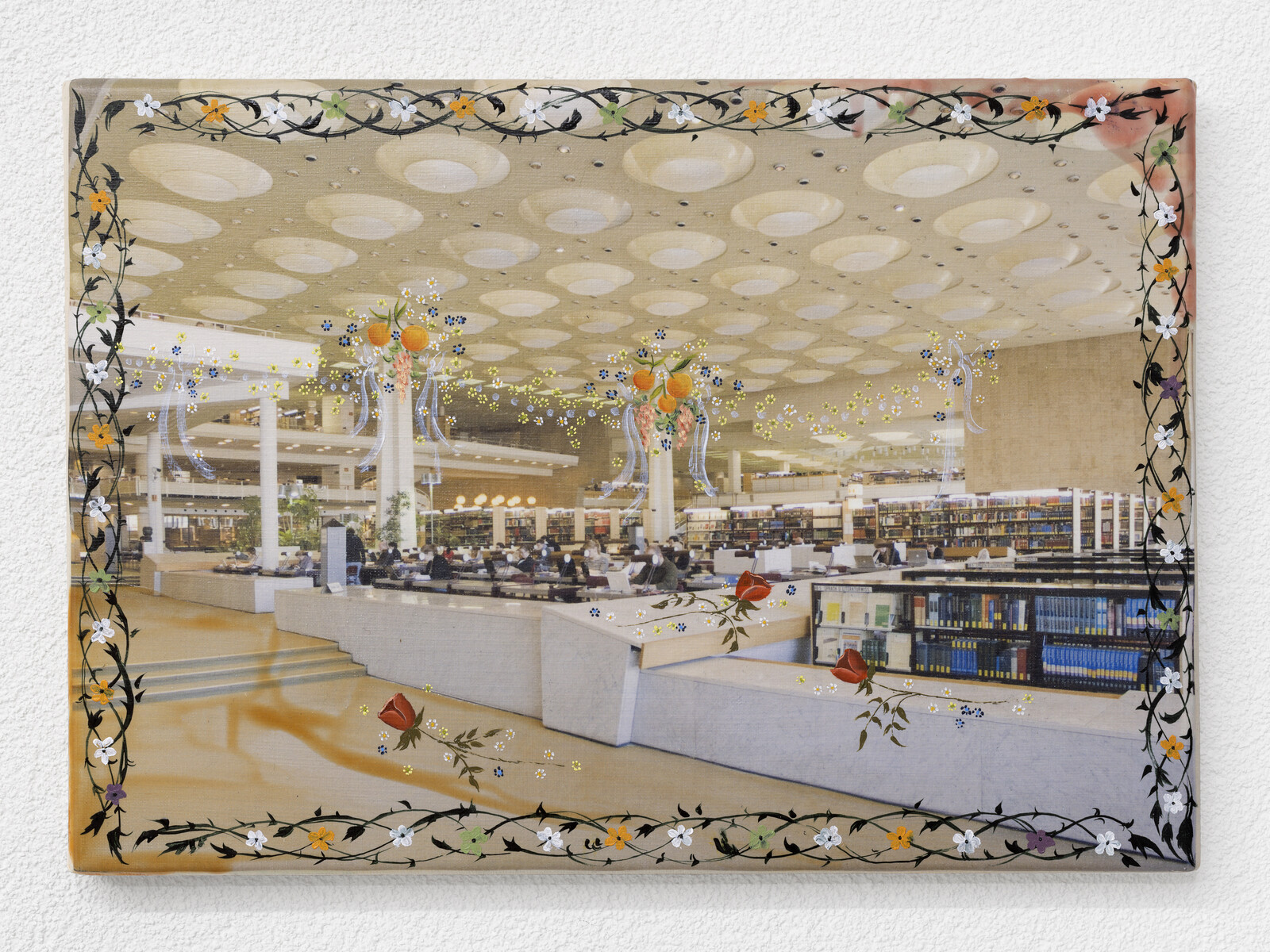

A Blank Slate

Reading the story today, it’s hard not to think of those luxury “burrows” being built in decommissioned missile silos for the protection of the ultrarich, or other gated palaces in which elites plan to sequester themselves from coming calamities. More generally, what The Trial and The Castle are for bureaucracy and legal procedure, “The Burrow” is for security architecture and surveillance: it dramatizes the will-to-safety, and its obverse, the anxiety of precarity and risk, that so dominate modern life and politics. Kafka analyzes, with clinical precision, what might be called the neurosis of security (a Freudian will recognize here a model of obsessional neurosis), with its fear of the enemy, its insatiable need for defenses and its imperative of constant vigilance—as well as its agonizing uncertainty, its postponed grand plans, and its vacillation.

Without time or space, a when or a where, without references to moment or place, the various versions of the question of how that inspire this conversation alleviate the task; they gather us under the assertion that we—and, I mean, black women—do, or rather create. Without asking for a program or a method, it is a statement.

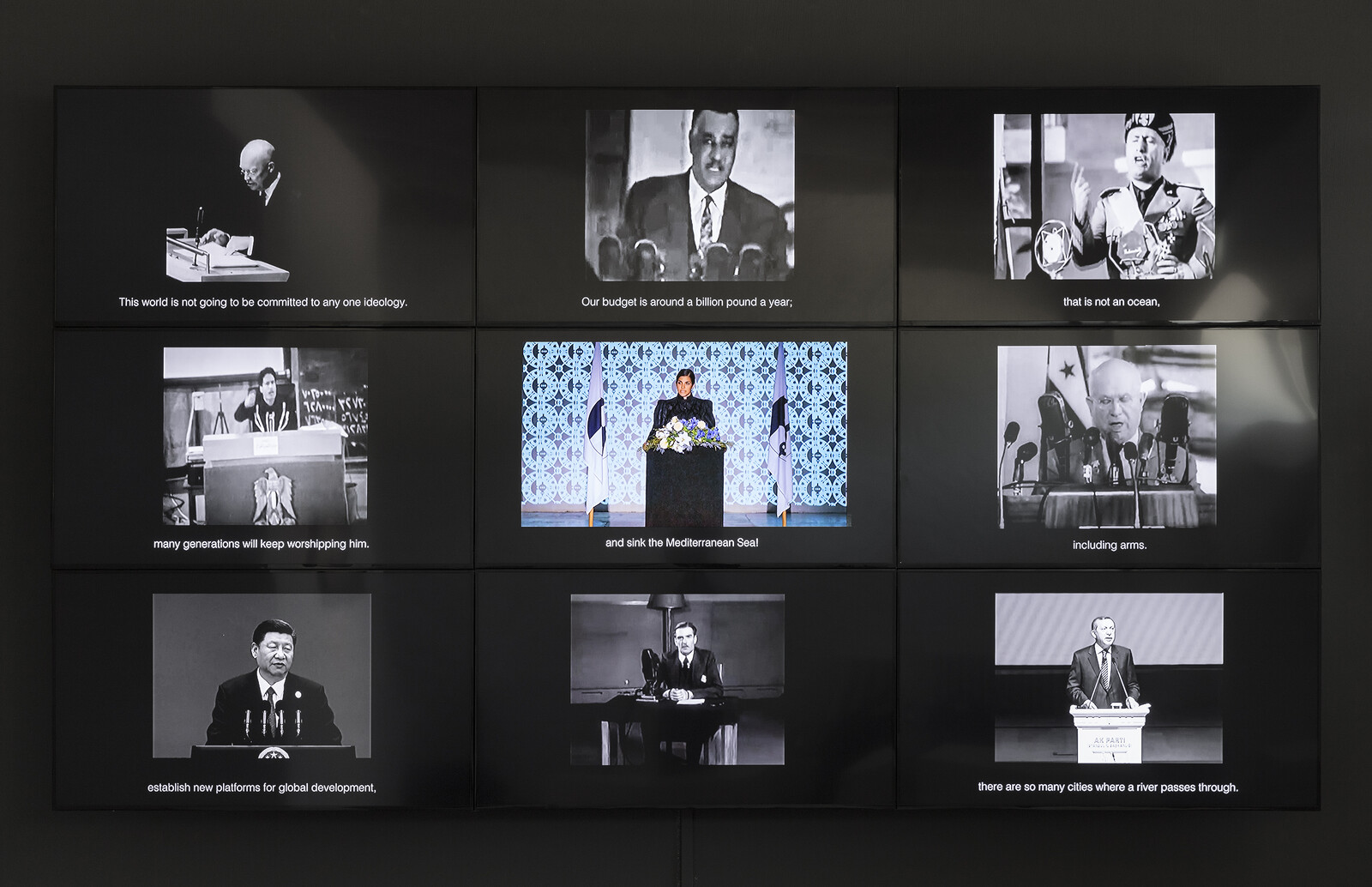

In culture, and particularly the contemporary visual arts, we should not underestimate the extent to which cultural workers themselves mimic the tropes of narcissistic authoritarian statism. We need look no further than Ai Weiwei’s 2016 recreation of a photograph depicting the death of Aylan Kurdi, a child refugee whose body washed up on the shores of Turkey. Weiwei cast himself in the role of the drowned child, as if the only way to raise awareness was to reenact the drowned refugee child, publicizing his image as equally strong as the actual event. Or consider Swiss artist Christoph Büchel’s work Barca Nostra (2019), presented at the 2019 Venice Biennale: he docked a vessel in which more than seven hundred people died on the night of April 18, 2015 on a pier in Venice’s Arsenale, next to a snack bar. In both cases, the narcissism of the artist employs neoliberal logics: their cultural capital is important enough to justify breaking codes of respect toward the dead.

But what does vulnerability actually mean? Is it being able to acknowledge a state of pain or insecurity, embracing the feeling of coming undone? I feel that it’s something I’ve tried to hide from others and from myself. At the cost of headaches, a bloated stomach, the inability to articulate a sentence. A mental-physical feeling of paralysis. I now suspect that people spend a lot of time and effort hiding in this way. Could I overcome my terror of falling apart if I allowed myself to rely on others, on you? Or should I be a “cruel optimist” and create hopeful and positive attachments, in full awareness that they will not work out?

“You meet the faceless man in a very ordinary setting…”

“Cosmology of the Spirit” proclaims the necessity of communism from the point of view of the universe’s immanent logic of becoming. In Ilyenkov’s text, communism turns out to be a much more serious historical and cosmic event, not limited to the scale of the planet. If the world still exists, this is because it was shaped by a previous cycle of the ontological machine whose necessary cog is fully actualized communist reason.