Tom Holert

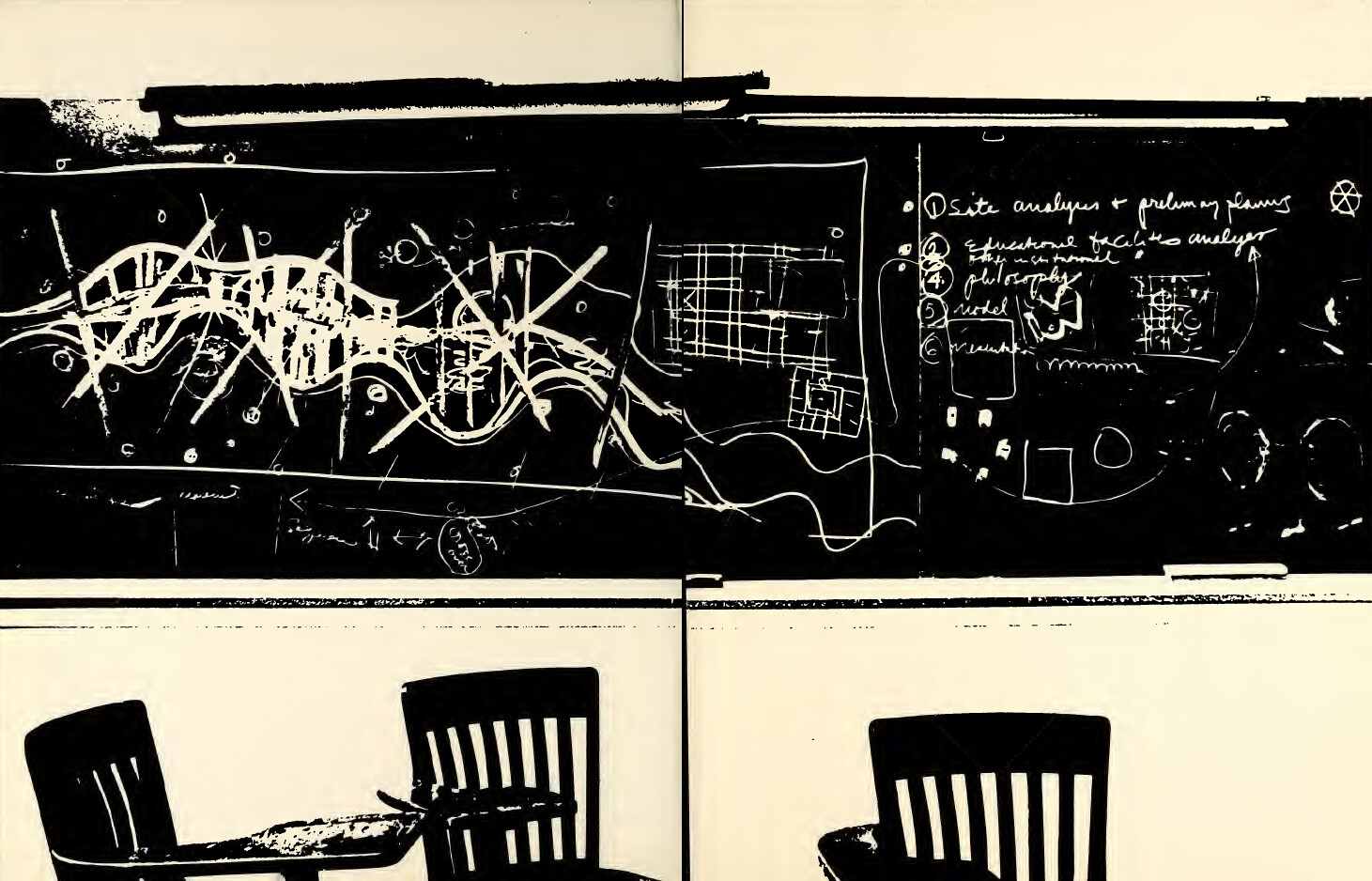

Navigation begins where the map becomes indecipherable. Navigation operates on a plane of immanence in constant motion. Instead of framing or representing the world, the art of navigation continuously updates and adjusts multiple frames from viewpoints within and beyond the world. Navigation is thus an operational practice of synthesizing various orders of magnitude.

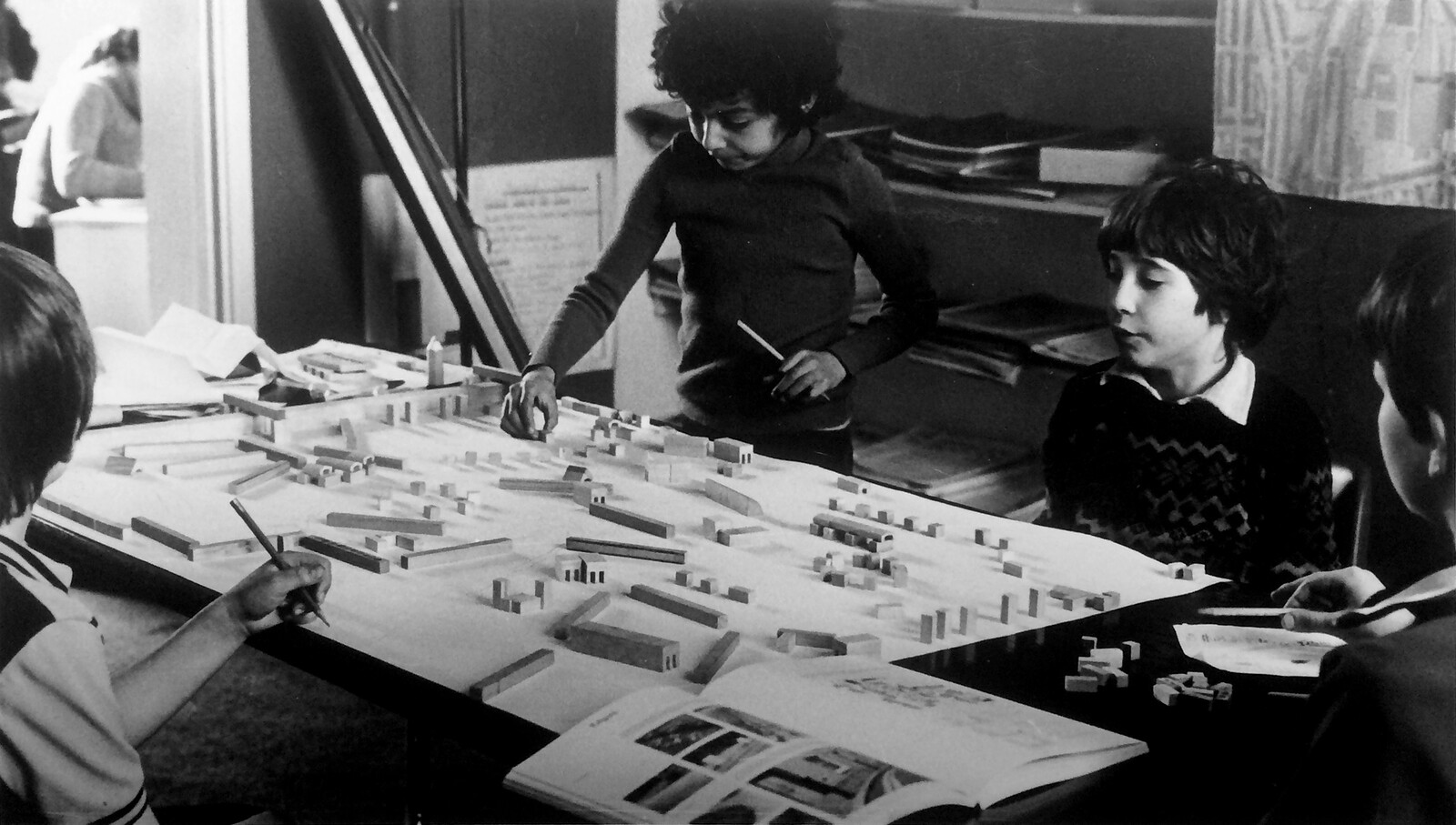

Parmigianino’s painting suggests that finding orientation should be conceived as a fundamentally tactile, sensuous, nonvisual matter (and, considering the pedophilic gaze impelled by the picture, a rather disconcerting one too). The boy’s hand, more than his vision, is the navigational device par excellence. It also serves as a precedent for another infamous hand of a boy with “a passion for maps” some four centuries later. Charlie Marlow, the narrator of Joseph Conrad’s 1899 Heart of Darkness, recalls his childhood dreams of “blank spaces on the earth.” “And when I saw one that was particularly inviting on a map,” Marlow muses, “I would put my finger on it and say, ‘When I grow up I will go there.’” Both hands, first in the sixteenth-century painting and then in the turn-of-the-twentieth-century novel, point to an evolving set of protocolonial, colonial, and neocolonial gestures that continue to inform geopolitical visual cultures. The hand is used as a scaling device, allowing one to literally touch the cartographic representations of often vast geographical areas, thereby making available an individual bodily experience of exploration, travel, and possession. In the mind deformed by colonialism, the touching of the map anticipates the grabbing of the land.

e-flux journal and Harun Farocki Institut present: “Art After Culture: Navigation Beyond Vision” at Haus der Kulturen der Welt

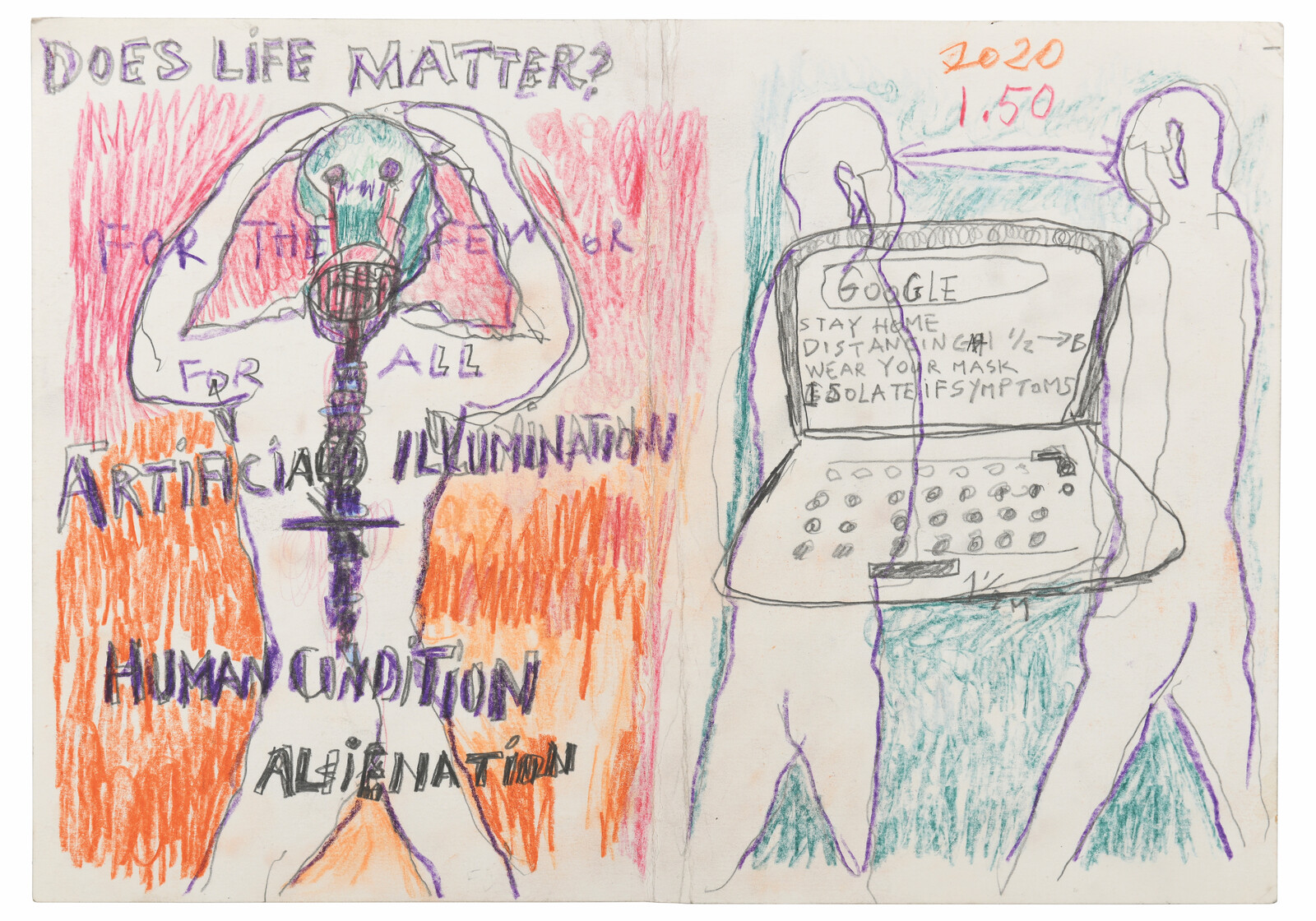

Photographic images could be considered particular forms of violence spurred by a given power/knowledge that is responsible for “general violence.” Conceived in this way, images could be performative as they enact ideology, as they exemplify, codify, and translate written and unwritten laws and social hierarchies, as they bestow or remove citizenship, and as they exert epistemic violence. Images do all these things in a particular mode and manner depending on the specificities of their respective medium and form. Visual activism, or the realm where images are put to militant use, like in the cases of Akhter and Ferdous, is one of the customarily invoked strands of practice that supposedly enables the production of visualities that oppose and contradict the “general violence” in which photography arguably takes part. So what exactly is the place of violence in activist image journalism and in modes of visual protest? And what may be the limit of such violence with regard to the violences of the (neo)colonial order?

Challenging our understanding of “design” by engaging with and departing from the concept of the “self.”

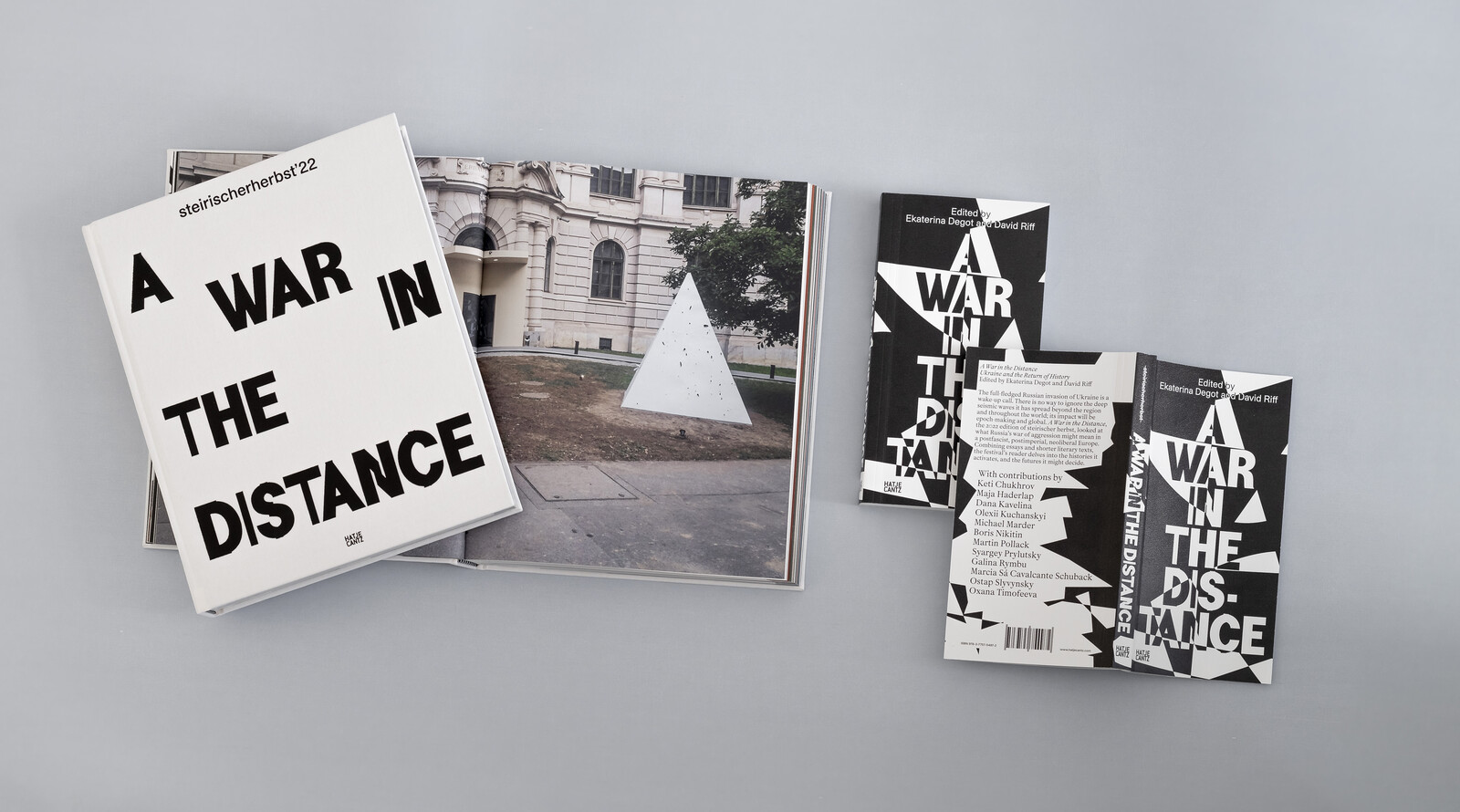

In more than 60 texts, first published on-site at 56th Venice Biennale, artists and writers trace the negative collective that is the subject of contemporary life.

Shine and shininess are characteristic of surface effects, of glamor and spectacle, of bling-bling contingency, of ephemeral novelty, value added, and disposable fascination. Shine is what seizes upon affect as its primary carrier to mobilize attention. Shine could be the paradoxically material base of an optical economy typically (mis)understood as being purely cognitive or immaterial.