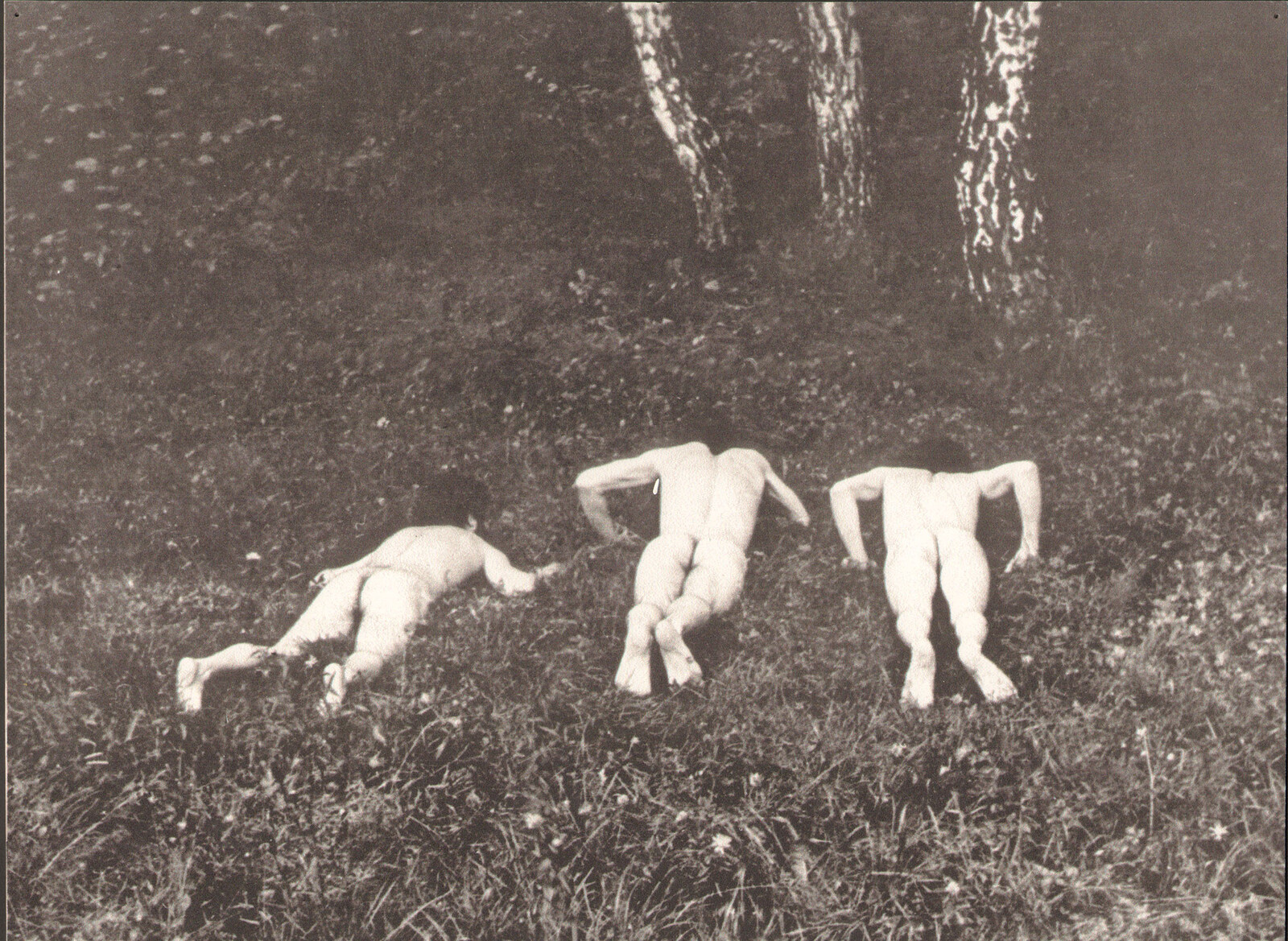

Christina Kiaer, Collective Body: Aleksandr Deineka at the Limit of Socialist Realism

The most interesting autotextual writing does one of two things, or even better, both: shows how selves are made, and makes room for a kind of self that otherwise barely gets to exist.

Dominique Routhier, With and Against: The Situationist International in the Age of Automation

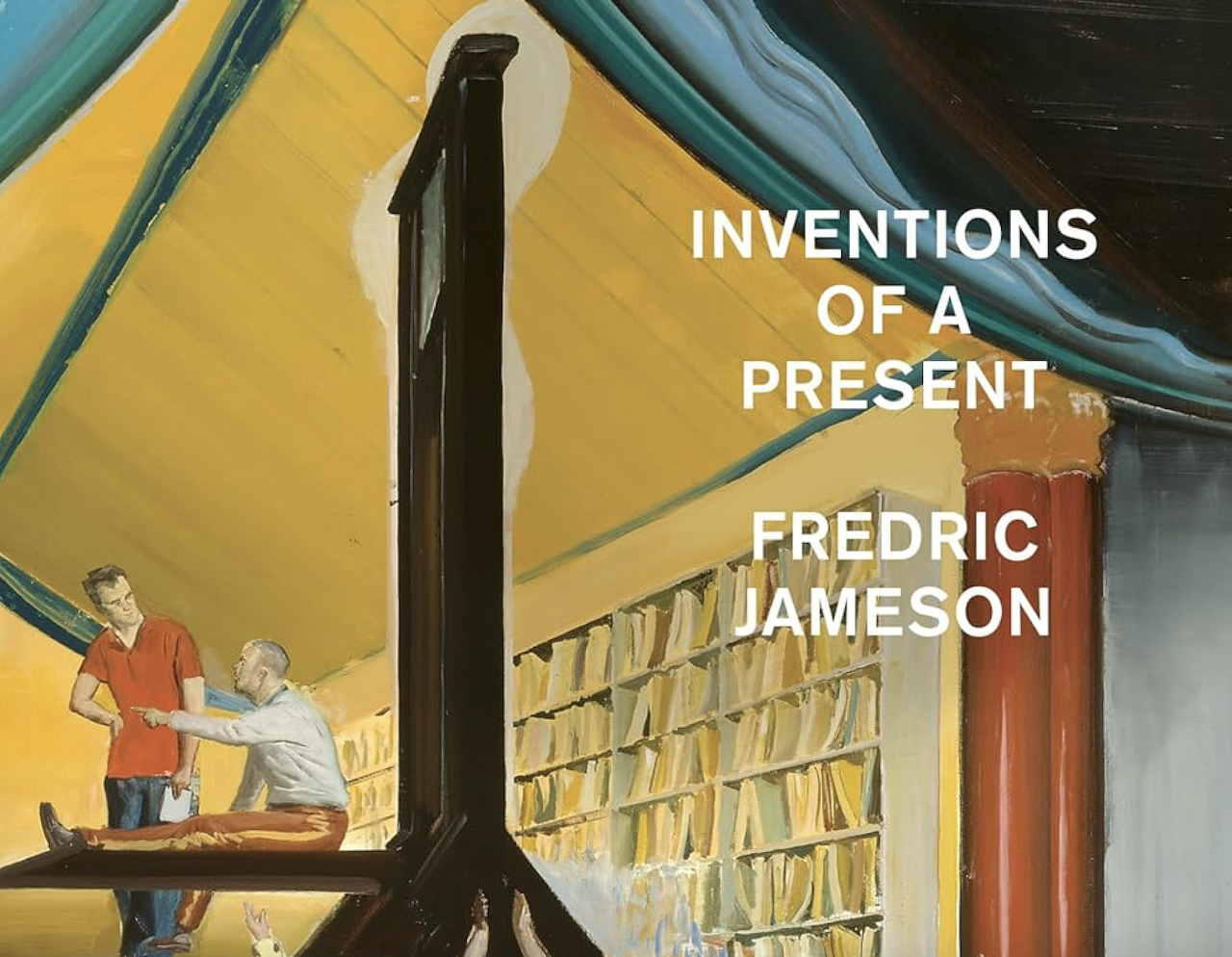

The object to be investigated here is no longer Latin American identity or cultural dependence, but the socioeconomic and ideological determinations of the plastic object. The premises have changed.

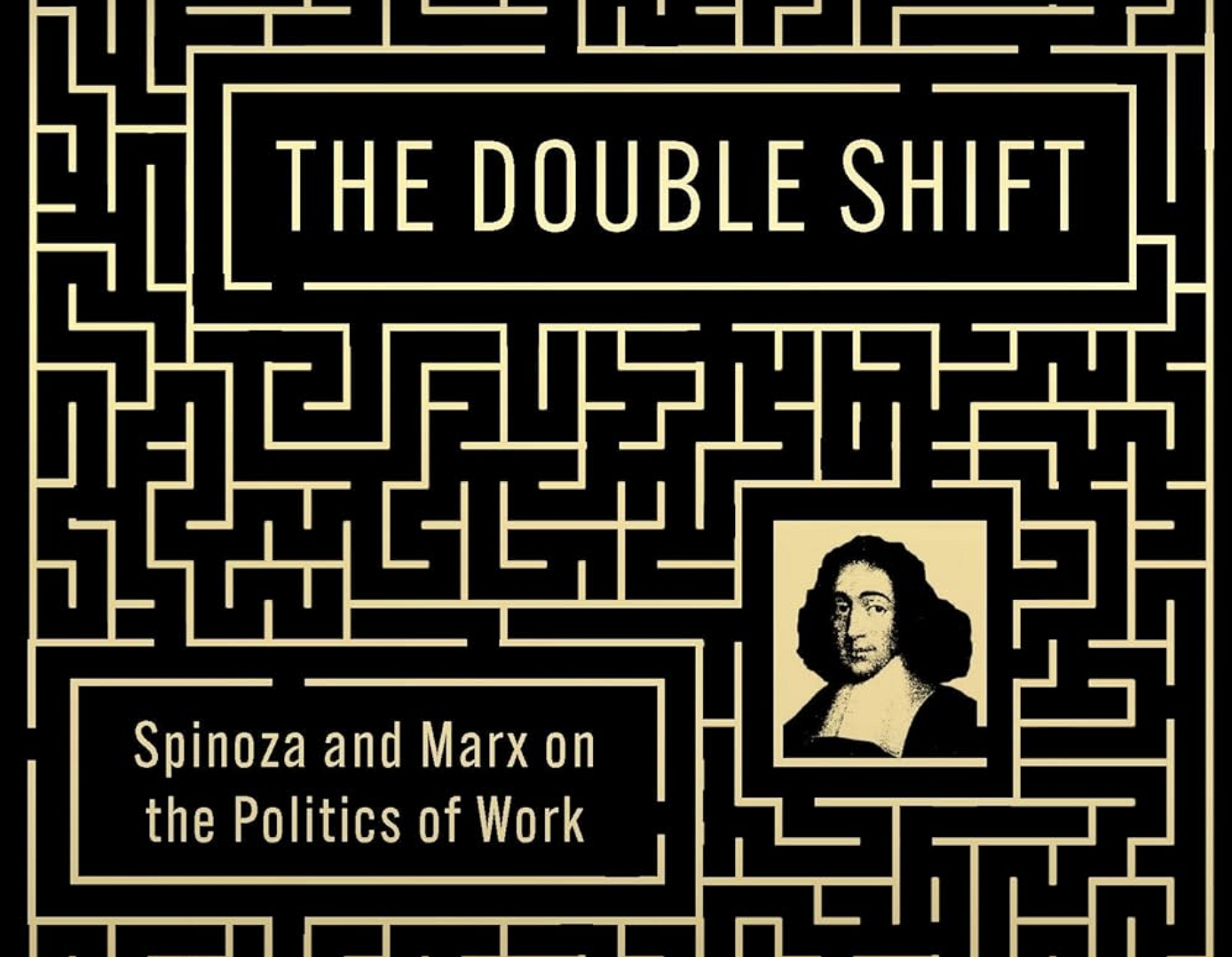

What do humans do after a successful revolution? The traditional answer is: they become the new masters and begin to impose their will on the losers. Indeed, such is the usual historical dynamic. However, Kojève believed that the working spirit—or rather the spiritualized working body—could be victorious over the animal human body. In other words: he believed that after the proletarian revolution succeeds, proletarians will continue working. But they will not work merely to live or satisfy their desires; they will work to maintain the spiritualized life-form their revolution achieved.

This is precisely what anti-natalism cannot grasp, or perhaps does not want to know. It does not see that pessimism is the fixed point around which its own enjoyment circulates. What singularizes the anti-natalist, what provides them with a specific way of going on, just is the view that the best is not to be born and that our ethical purpose now is to bring about the extinction of the species by refusing to procreate. This is a life that sets itself against life, that carries death at its very core; but it is a life, nevertheless.

Beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the term “wisdom” appeared very frequently in Soviet philosophy publications. It was used to better situate the doctrine of dialectical materialism within the history of philosophy as well as in relation to science, art, religion, and so on. Dialectical materialism was itself conceived as a form of “wisdom”: that is, as an insight into the whole of the world which was fundamentally lacking in science and art.

Gnosticism needs a prophet—the unmasker, the Revealer, who will open the people’s eyes to the hidden truth: that spiritual substance has fallen into the state of matter, but that it is to be found everywhere (as prima materia), and that universal salvation is in the hands of one and all. Consequently, Gnosis (i.e., Knowledge) and its prophet, Savior (soter), play a central role in the Gnostic/Hermetic tradition. In ancient texts, Simon the Sorcerer (Simon Magus)—the archetypal figure of the Gnostic savior—comes to show the people that Limitless Power is within them. Marx appears seventeen hundred years later for the same purpose. Unlike his orthodox Christian counterpart, the Gnostic savior comes to reunite every person (including himself) with his authentic Self.

“Seeing appearances as the shortcomings of a prior state of true being is indeed boring, I agree.” Warmed by the drinks, I’m warming to my theme. “Let’s work the surfaces, change the signs, fashion the possibility of a kind of being to come! We are not fallen imitations of cisters. We are prototypes of the bio-hacked beings to come! We add to the range of things that humans already edit about their bodies. We do it with the latest techniques, the latest information, in all fields. We are among the avant-garde of possible future humans. What if a world existed that could answer to the desires of our bodies?”

The discourse of Marxism, on the contrary, produces not trust but distrust. Marxism is basically a critique of ideology. Marxism looks not for a “reality” to which a particular discourse allegedly refers but to the interests of the speakers who produce this discourse—primarily class interests. Here the main question is not what is said but why it is said.

Popular religiosity, Sophiology with its Fedorovian, cosmist charge, and the alchemical unconscious of Marxist theory are the three distinct but in some ways related “holy families” of Russian immanentism. On the level of ideas, the various members of these families are easily coupled and hybridized, despite their heterogeneity. In consequence, we witness the emergence of a kind of ideological field of integral immanentism in the first decade of the twentieth century.