Sylvia Lavin, “Generator’s Vital Infrastructure”

The collapse of reality is not an unintended consequence of advancements in, for instance, artificial intelligence: it was the long-term objective of many technologists, who sought to create machines capable of transforming human consciousness (like drugs do). Communication has become a site for the extraction of surplus value, and images operate as both commodities and dispositives for this extraction. Moreover, data mediates our cognition, that is to say, the way in which we exist and perceive the world and others. The image—and the unlimited communication promised by constant imagery—have ceased to have emancipatory potential. Images place a veil over a world in which the isolated living dead, thirsty for stimulation and dopamine, give and collect likes on social media. Platform users exist according to the Silicon Valley utopian ideal of life’s complete virtualization.

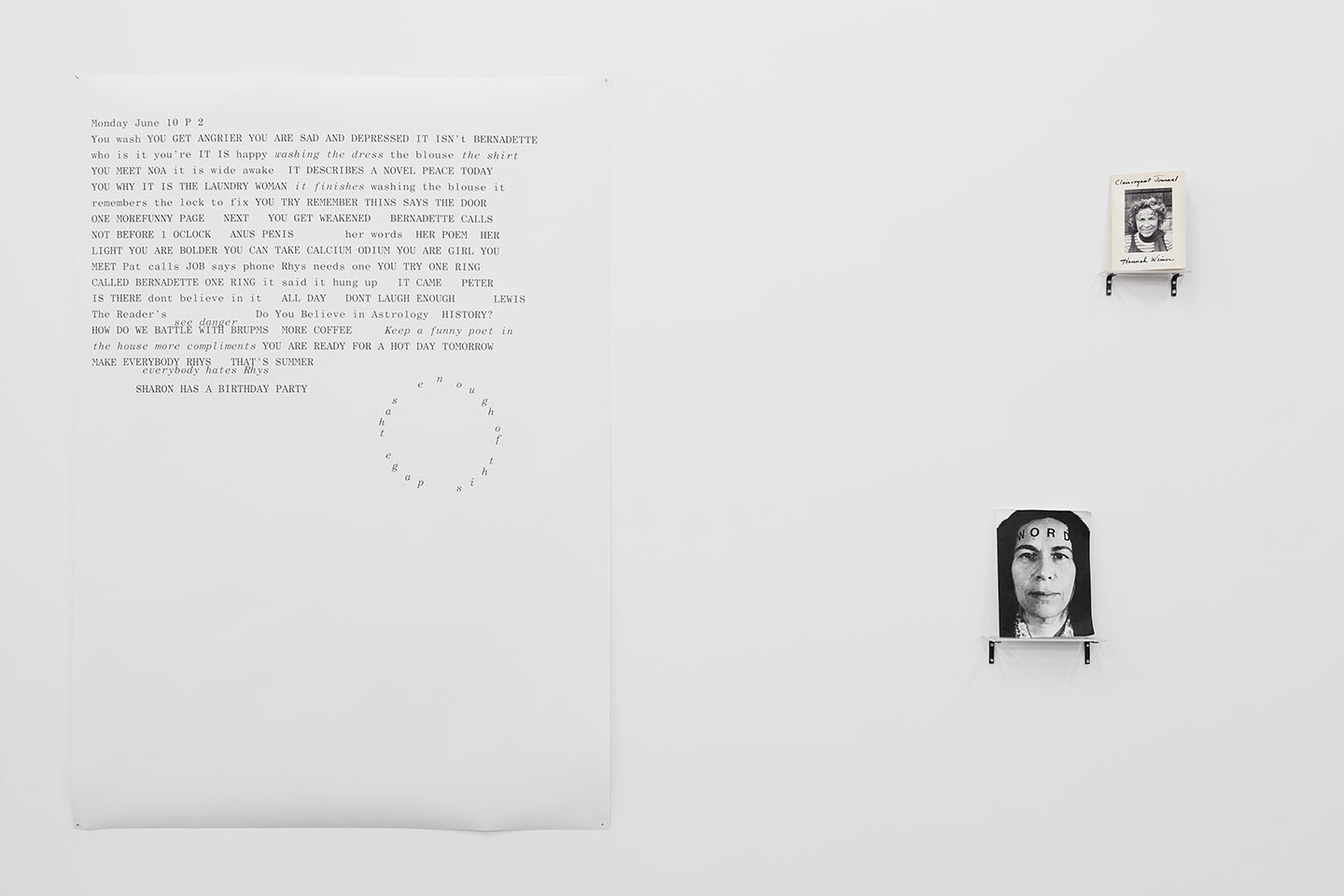

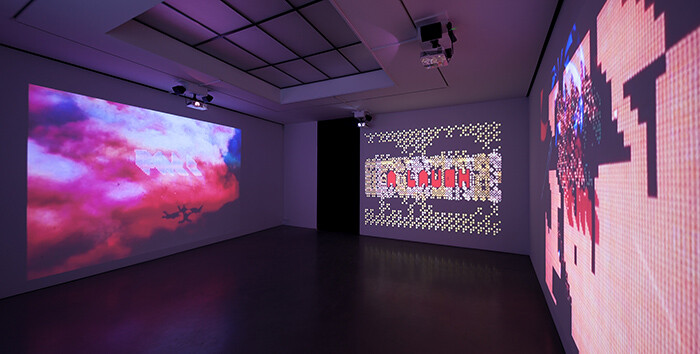

How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File

What is life in a world where I am also the architecture of that world? Until recently, the history of Western scientific development has been a history of a brutal spiritualism, where discoveries of cosmic mechanics only further displace the human observer. I might gain access to God’s computer in a quest to commune with higher forces, only to progressively discover that material forces are programmed as an inhospitable abyss in which my life means nothing. Science might come to the rescue to draw these material forces back under human command, weaponizing and industrializing their power to limit their threat. From Descartes conceding that we possess an exceptional soul in spite of being animate machines and Darwin’s allowing us an aristocratic status in spite of being animals, a brutal self-extinction has haunted (perhaps even guided) the European spiritual imaginary since the Enlightenment. We might eventually consider that mechanical forces and animal survival might have better things to do than conspire to exterminate our human kingdom the moment we observe them. In the meantime, we still need to contend with a world or worlds that serve our every need in the absolute, even amplifying them into architecture, sealing us in and serving us at the same time.

In light of current discourses on AI and robotics, what do the various experiences of art contribute to the rethinking of technology today?

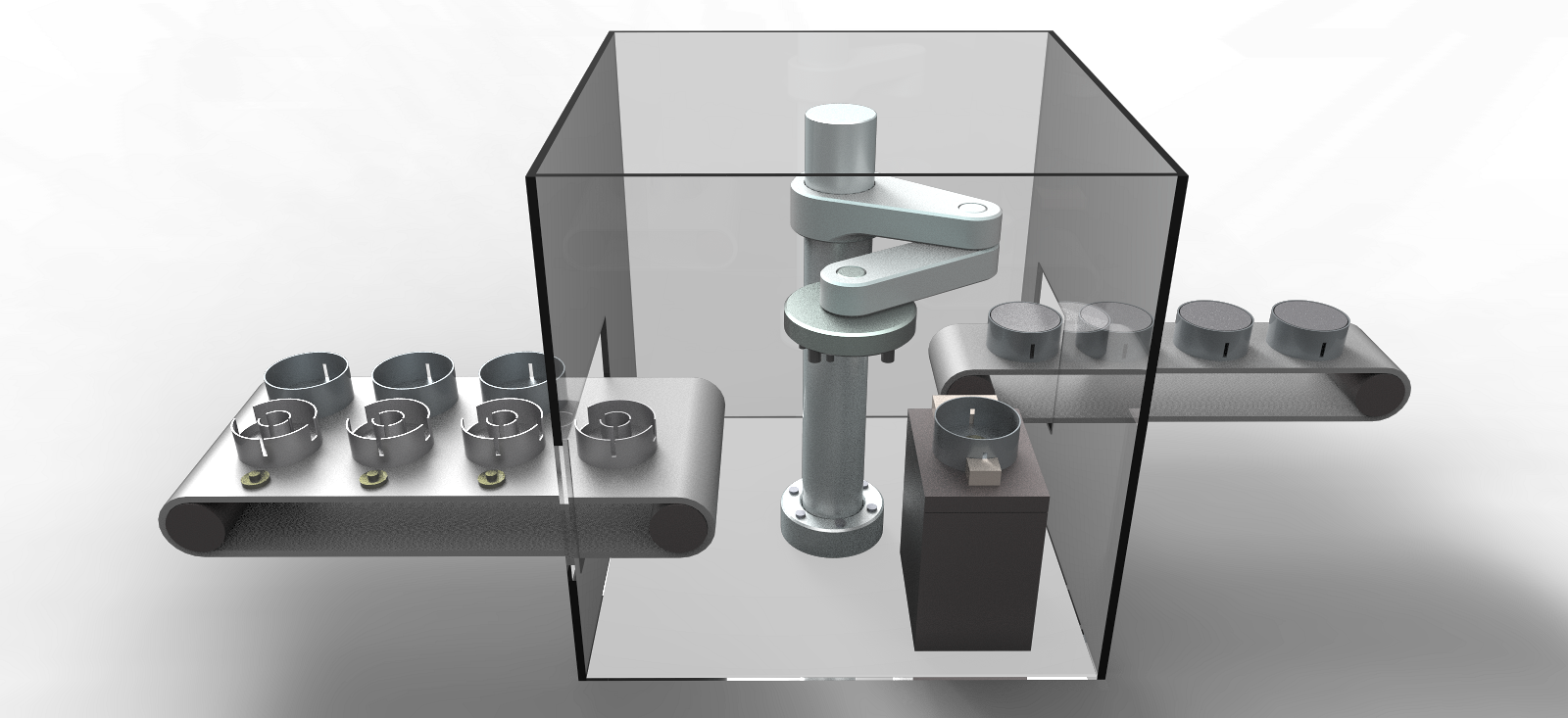

YH: We live in an age of neo-mechanism, in which technical objects are becoming organic. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, Kant wanted to give a new life to philosophy in the wake of mechanism, so he set up a new condition of philosophizing, namely the organic. Being mechanistic doesn’t necessarily mean being related to machines; rather, it refers to machines that are built on linear causality, for example clocks, or thermodynamic machines like the steam engine. Our computers, smartphones, and domestic robots are no longer mechanical but are rather becoming organic. I propose this as a new condition of philosophizing. Philosophy has to painfully break away from the self-contentment of organicity, and open up new realms of thinking.

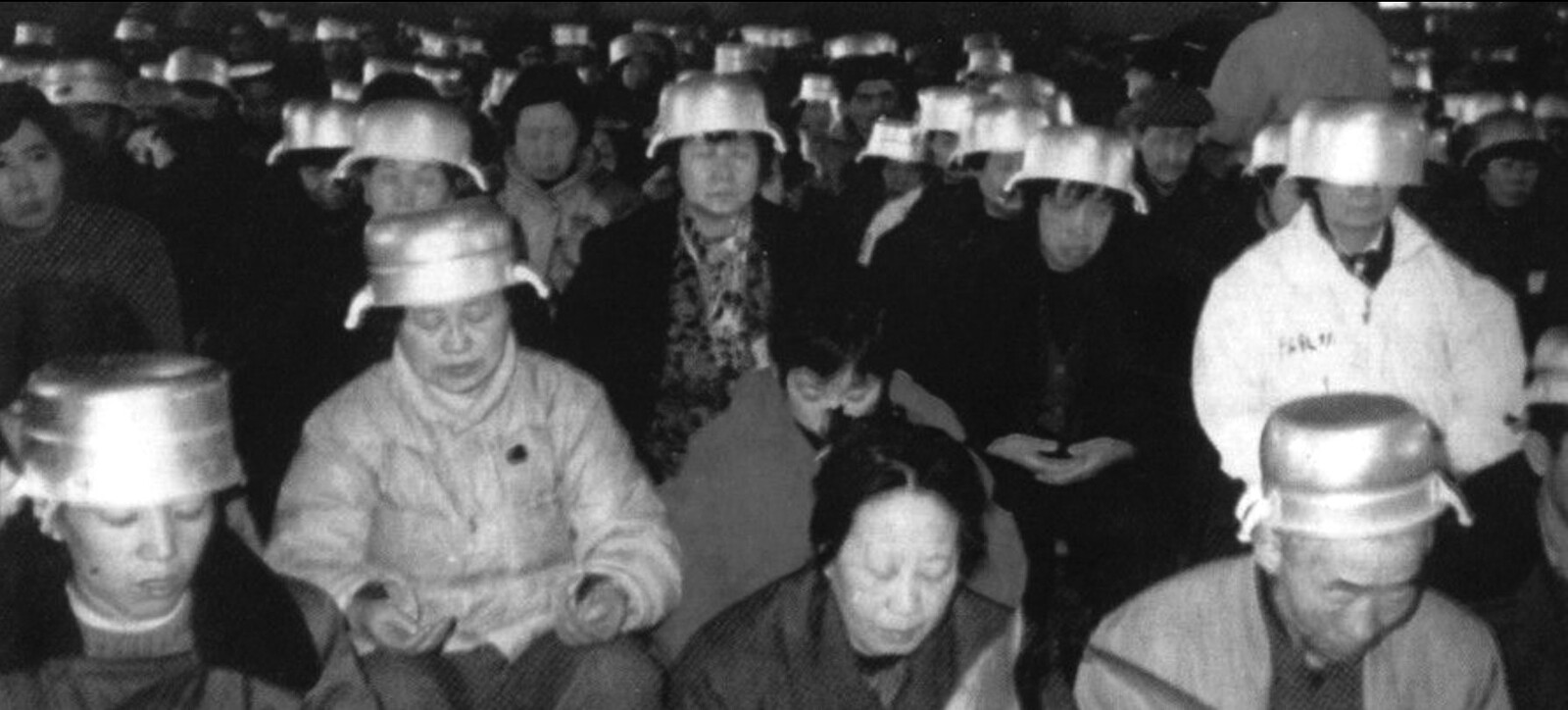

The human body as a medium is not a new phenomenon. Traditional Chinese philosophy and religious practices, as well as spiritualism in the nineteenth century, had featured different versions of the body-as-a-medium within different epistemological modes. The increasingly pervasive computational environments bring the human body to the center of current media studies, especially in the new media scholarship on digitization and networks. But the emergence of an “information body”—the body as a medium for information processing—in China in the 1980s, on the one hand, registered the ways in which contemporary media technologies transform the perceptions and interactions of the human body with the world, and, on the other hand, was a discursive construction deeply entrenched in the politics of the postsocialist world, accompanying the production and unleashing of consumer desire in the process of marketization, and concurrent with the privilege of “information workers” over factory workers and peasants, who were once valorized as socialist subjects. This “information body,” however, is not merely a passive receiver or transmitter of information.

Computational indifference to binary problem-solving coincides with a new imperative: technological decisionism, which values making a clear decision quickly more than it does making the correct one. For decisionism, what is most decisive is what is most correct. When Mussolini gives a speech in parliament, in 1925, taking full responsibility for the murderous chaos his regime has created, and challenging his opponents to remove him anyway, he is practicing decisionism at the expense of binary logic, which would dictate that if Mussolini is responsible, then he should resign. Instead, the dictator declares that he is responsible and that he will stay. Today it is our machines who make these speeches for us.

Soviet society was hypnotized by the notion of technological acceleration at the same time as it was overwhelmed by frustration and boredom. The economy was weighed down by a constant state of crisis, yet no credible scenarios of reform were deemed acceptable in public discourse. The political system showed signs of imminent collapse, yet no viable alternative was anywhere in sight, apart from the idea of more of the same—more growth, more productivity, more speed. In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev came to power, proposing a program to radically overhaul the economy and society. His plan was based on three notions: perestroika, glasnost, and uskorenie. Perestroika and glasnost have entered the English language as “restructuring” and “openness,” respectively. But the third part of this triad, uskorenie, is not at all well known: it means “acceleration.”

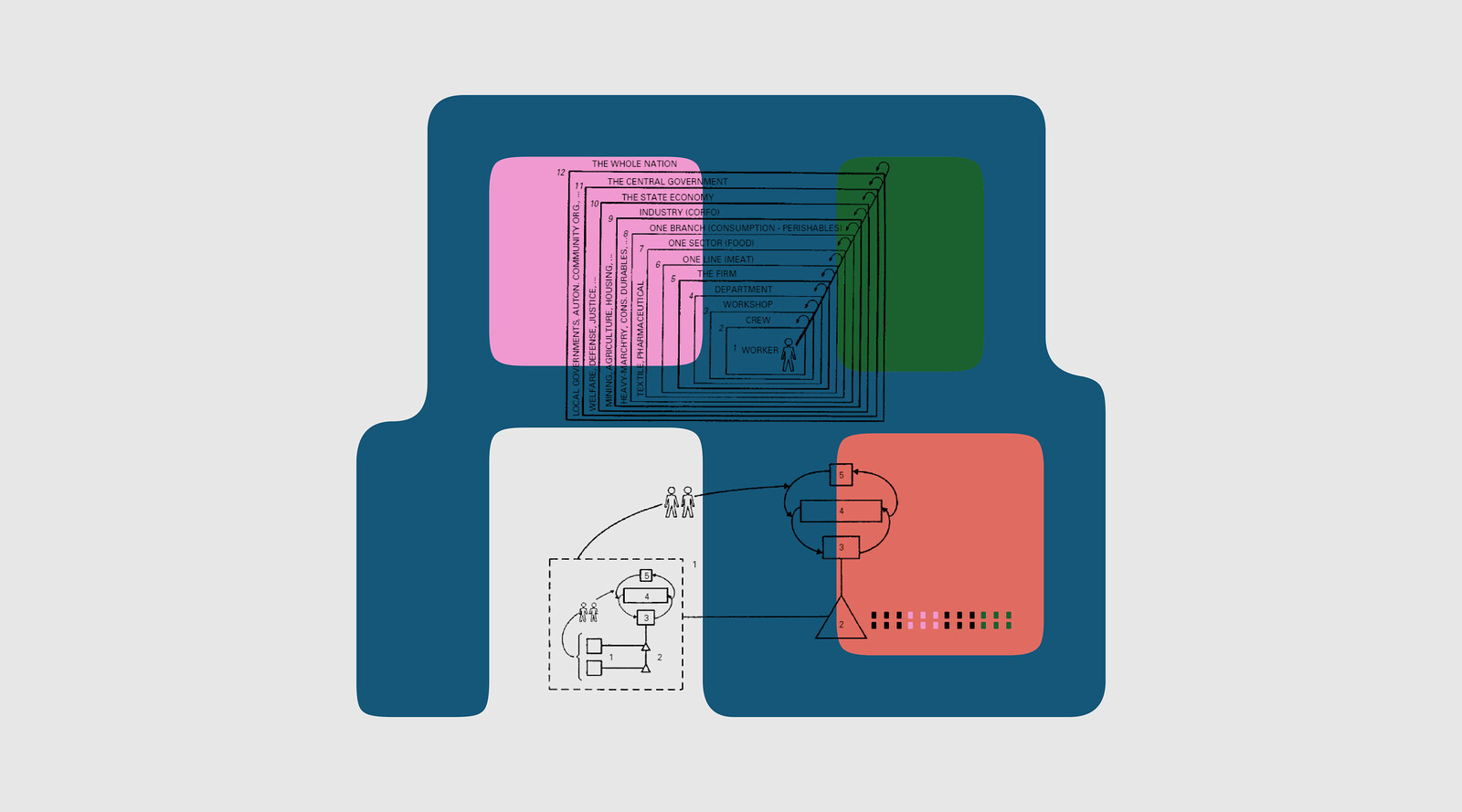

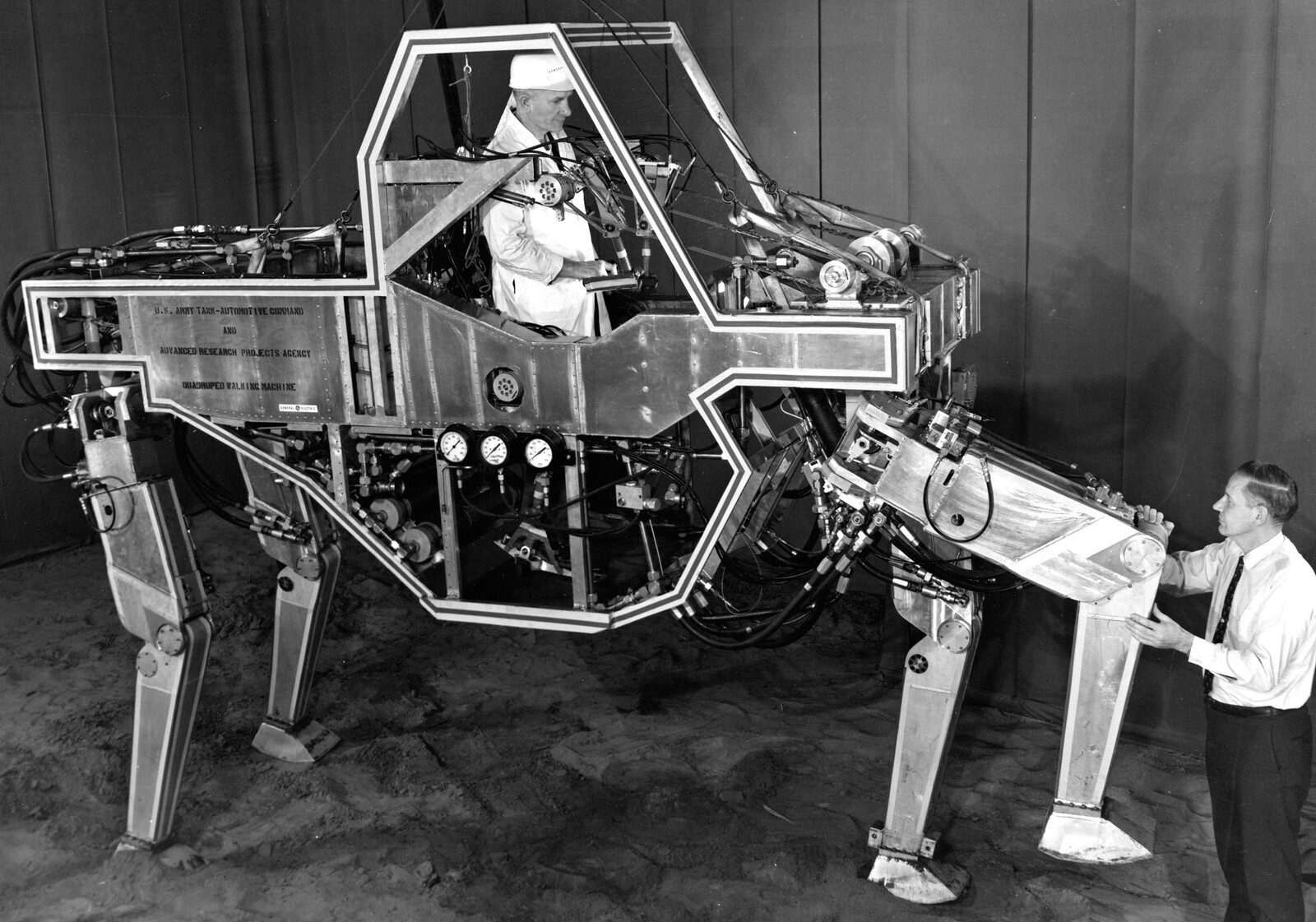

Cybernetics, in its ambition to unify the natural and social sciences, and even the humanities and the arts, is a relic of the massive cross-scientific endeavors of the Second World War. For many, this science of control and communication promised a response to social and economic issues that seemed especially pressing. “Control” and “communication” were, of course, central preoccupations for societies whose economic policies were based on Keynesian “social planning,” whose hierarchical, multilayered corporations raised new problems of management, and whose deskilled manufacturing system put control over the content and pace of production in the hands of a professional-managerial class. Cybernetics, unsurprisingly, appealed to corporate management, military engineers, or government technocrats, as it promised a more efficient and less violent means of managing complex processes.