I walked straight past the entrance to Pilar Corrias’s gallery. The lights are off and inside it’s dark and quiet. The only work on the ground floor is Sam Lewitt’s A Weak Local Lexicon (MHTL) (2016), an unlit installation which converts the charge from the light source, powered from a distribution board in the wall, into heat emitted through four custom-made copper-plated panels lying on insulation blankets on the floor. Wires lead out from the mains in the wall to connect each panel, regulating the room’s moderately high temperature, altered slightly by my entrance. Little digital meters sit atop the panels, giving numeric readings of the oscillating flow. Their red blinking is the only visual noise of this otherwise ascetic piece.

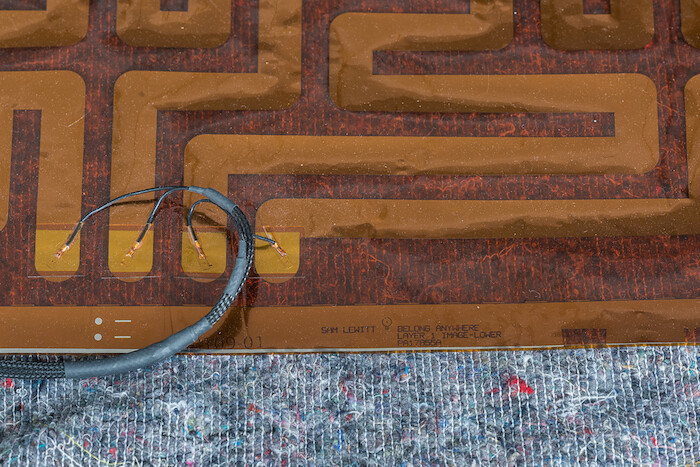

The work began life among others in Lewitt’s solo exhibition “More Heat Than Light” at San Francisco’s CCA Wattis (2015) and Kunsthalle Basel (2016). Its copper patterning is custom designed to reflect the fretwork on the exterior of a Basel bank vault. This Ancient Greek motif, of a continuous line meandering towards infinity, symbolizes Lewitt’s long-term interest in technology’s deployment by capital, the process of circulation similar to that David Harvey describes in which “money is perpetually sent out in search of more money.”1 The pattern also maps the infinite flow of the affective worker. Lewitt has subtly inscribed within the copper fret corporate tag lines targeting us to “belong anywhere” (AirBnB) or “get connected” (Microsoft), new technology-led services enabling, or rather nagging workers to travel globally, communicate constantly, and move hyper-flexibly. But that restless bodies find stillness here in the dim light and Lewitt’s work—possibly also attributable to its gentle heat—is oddly calming.

Perhaps because of this warmth there seems little of the acerbic institutional critique that previous conceptual artists (such as Michael Asher’s Vertical Column of Accelerated Air, 1966-7 or Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube, 1963-5) began by altering a gallery’s environmental conditions. Neither does it resemble the solemn critique of technology as financial institution in recent exposed cable installations by Ben Schumacher (Long Lines 33, 2013), Yuri Pattison (user space, 2016), or Eva and Franco Mattes (Dark Content, 2016). There is certainly a significant sense of inquiry here but to the question of what techno-capital needs in order to survive it implies an answer rooted in the human body, like an earth wire regulating the electrical power circuit, socially responsible for other bodies (or wires) but ultimately susceptible to breakdown when subject to unforeseen surges.

Lewitt’s work creates a decompression chamber for the exhibition’s second big piece, Lucy Raven’s Casters (2016). Raven is as interested in the evolution of moving image—from the (relatively) flat early animations to the (relative) fullness of digitally rendered 3D—as she is in the industrial and post-industrial forms of production that create their respective effects. Her work has simultaneously charted flat images being brought into relief with the cheap labor forces that produce these illusions in global post-production units: cheap Chinese and Indian assembly lines rendering digital effects frame-by-frame for wealthy Hollywood studios (Curtains, 2014, and Low Relief, 2013).

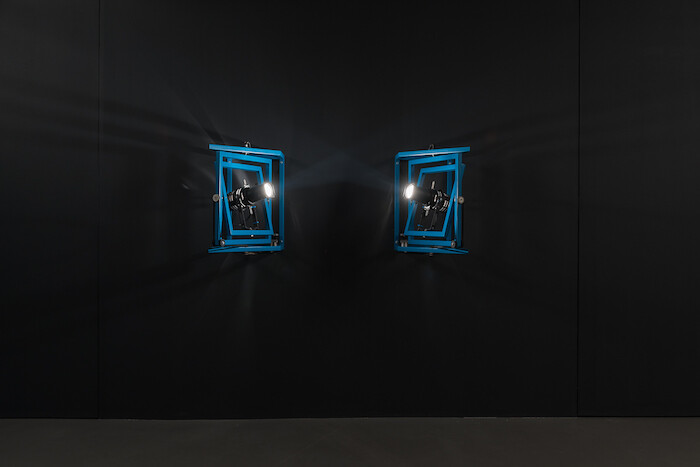

In the gallery’s darker, smaller downstairs space, two 575 Watt lamps are mounted abreast of one another into aluminium rotocasters fixed to the wall. Rotocasters are machines that enable the casting of forms, where the mold is rotated in two directions simultaneously to dry the cast evenly. The resulting hollow forms can be cut open into shells, or back-filled to create solid objects. So what comes out of the rotocaster is a transitional or enabling object rather than, necessarily, a thing-in-itself. What spills out of Raven’s two mounted lamps are also typically transitional, enabling: spotlights that rotate slowly around the space. But here they are set free, independent of other objects’ thingness, to become things-in-themselves. Their mechanized movements are mirrored and in sync, their dual projections bisecting the space in diagonals, crossing one another in a steady, silent infinity curve. It is difficult to escape their pathway, so these spotlights pass over my body at intervals, just as Lewitt’s heat sensors responded to my temperature. Casters occupies the transition from flat image to round thing, while its industrial machinery explores how power will always materialize, tangibly, on the ground.

The exhibition presents an inspired pairing of two artists adept at exploring the complex dynamics of power, and how capital is felt at different points of its production. And while initially the ebb and flow of infinity loops provides a serene encounter, a devastating contradiction rests at its core. Raven’s light rises and falls over me repeatedly as I stand in the quiet basement of a noisy city at the center of a country divided, where a calamitous imbalance of wealth and poverty long felt and recently voiced has wrecked the illusory loop of prosperity, among other greater systems.

David Harvey, The Enigma of Capital: And the Crises of Capitalism (London: Profile Books, 2010), 40.