For much of its century-long history, the BBC has been an object of nostalgia in Britain. It began as a private company, and in 1927 a royal charter decreed its mission to “inform, educate, and entertain” the nation; the corporation is funded today by a television license levied on all households that watch its output. The public-service remit always appears to have been better fulfilled in the past, during a vague and movable golden age. Public service, of course, has rarely meant public access or participation. An exception was the work of the Community Programme Unit, which in 1972 began soliciting program ideas from interest groups and campaigning organizations. Around three in ten proposals were accepted; successful applicants were then provided with a small budget, a production team, and a final say in the show’s edit—subject to legal niceties and the BBC’s sometimes vexing commitment to “balance.” Copies of the finished programs were given to the groups who devised them, but most were never broadcast again. “People Make Television,” an absorbing exhibition at the newly reopened Raven Row, includes over 100 of the CPU’s programs (alongside other public-access projects of the time), and seems to conjure a genuine lost era of politically engaged and engaging television.

Some of the material—forty-minute programs, originally shown late on Monday evenings—felt immediately apt or relevant to contemporary Britain, now thirteen years deep into the effects of Conservative policy and whim. In Black Teachers (1973), the writer Mike Phillips described the work of a group of Black educators from Liverpool, and likened (with diagrams) the structures of school governance to forms of colonial bureaucracy. In March 1981, the Joint Working Group for Refugees from Latin America contributed a program called They Came for Us in the Morning…—this in the period of Margaret Thatcher’s enthusiastic political and military dealings with the murderous regime of Augusto Pinochet in Chile. Speak For Yourself—produced by the commercial channel London Weekend Television, under the CPU’s influence—addressed a housing crisis facing single people in London: decaying accommodation, impossible rents, homelessness even among those with jobs. On 4 June 1973, 500,000 people watched a studio discussion and case-study films by the Transex Liberation Group: a program notable today for the absence of “balancing” anti-trans voices.

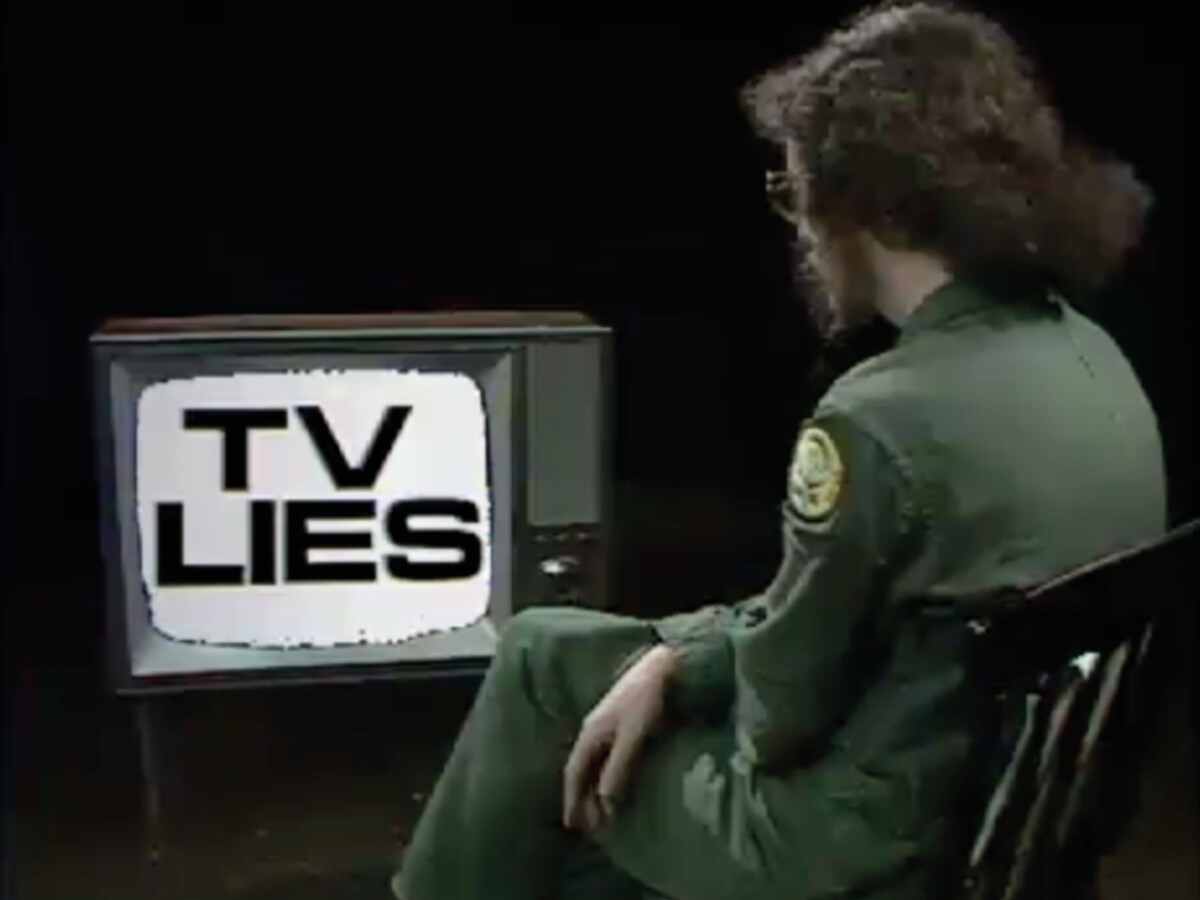

At Raven Row, you watch these programs (sometimes from a sofa, with remote in hand) on large CRT monitors in wooden cabinets; actual domestic sets of the time would have been smaller, frequently rented rather than owned, prone to maddening breakdowns. In the exhibition catalog, William Fowler and Matthew Harle (co-curators with Lori E. Allen and Alex Sainsbury) write: “Open Door episodes possess a texture and form unlike any broadcast media of its age.” This is partly true: in the on-screen presence of televisually untutored factory workers, travellers, and “housewives”; in the handmade signs and backdrops arrayed behind them. But it’s striking too how frequently programs mimic the structures of conventional television, especially the magazine format, with its in-studio panel discussion and location interludes on 16mm film. At times, Open Door studio anchors try out the tics and mannerisms of their famous counterparts. It is almost possible to believe that a presenter in November 1973 (helmet of blond hair, gold jewelry) is a mainstream BBC personality—except she’s speaking very plainly about cystitis, its symptoms and remedies.

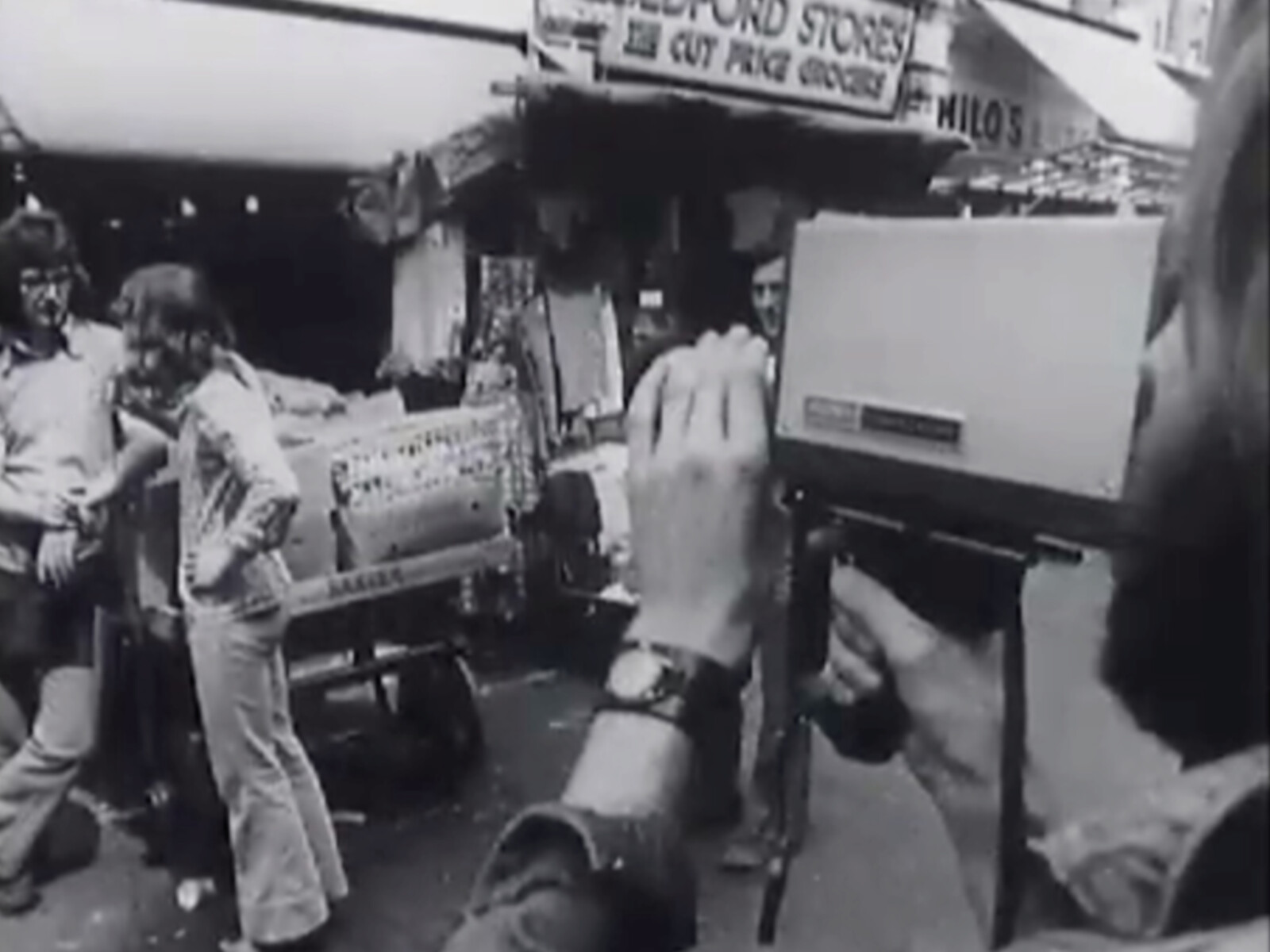

“People Make Television” excerpts programs only from the CPU’s first (more experimental and collaborative) decade. It is not quite the case that the BBC’s regular output at this time maintained, by contrast, a seamless corporate surface. Bouts of amateurism could erupt in children’s or pop-music programming; in live settings, the public sometimes overstepped the bounds of decency and balance; in the early 1980s, “yoof” (genuine period term) television often exposed its own workings in the name of postmodern self-reference rather than authenticity. Less evident in primetime: the kind of sustained access Open Door made possible to unrepresented constituencies, but also to the visual modes by which they already operated. A CPU program by the Cleaners’ Action Group shares footage and participants with the better known Nightcleaners, made between 1972 and 1975 by the Berwick Street Film Collective.

The CPU was unable actively to commission programs, so was sometimes slow to respond to contemporary events, or missed out on them entirely. Southall on Trial (1979) details police brutality towards anti-fascist protestors in West London; but the “riots” (provoked by racist police practices) of 1981 in Liverpool, Birmingham, and London are nowhere to be seen. The structures of public-access programming could also work against the CPU’s commitment to minority voices, a fact the exhibition doesn’t quite demonstrate. While the show does screen an absurdly misogynist 1978 polemic by the Campaign for the Feminine Woman, a program from two years earlier by the British Campaign to Stop Immigration, complaining of a “sinister veil of censorship” on the issue, is not there. There’s no reason it should be; but the controversy around it (and attendant BBC memos) would have accented certain ambiguities in the CPU’s mission. These caveats aside, the exhibition gives an unusually considered but expansive view of a cultural-political history that didn’t come to an end with the closing of the CPU in 2004. We live now in the largely individualist media aftermath of movements originally conceived (in fly-on-the-wall documentary as well as open-access television) as conduits to collective thought and action.