Marvin Gaye Chetwynd’s practice, with its hubbub of miscellaneous and licentious references, evokes a mood of historic and anthropological ambiguity. Her works enmesh periods of cultural rebellion over the centuries, from medieval history, folk plays, and pagan festivals, to the genesis of Dada, and from the DIY culture of drag balls and punk to alternative living, squatting, and co-ops. Chetwynd’s spontaneous intertwining of performance, installation, video, sculpture, and painting can also be figured within the space of play: an arena dedicated to experimentation and risk without a predetermined outcome. This gesture toward facilitating an impermanent escape from reality is best read through Mikhail Bakhtin’s theories of the carnivalesque: free interaction between people; eccentric or non-traditional behavior; sacrilegious events; and the nonsensical (mis)alliance of opposites.1 Absurdity, humor, and hyperbole are de rigueur. The world is upside down. The body is inside out.

Chetwynd’s topsy-turvy approach to performance is expressed in a quieter register in her solo show at Sadie Coles HQ. Ten colorful, collage-like pieces are hung on the gallery’s walls, while three illustrative paintings—one (Samurai Bat) depicts a bat’s head; another (Dulac’s Perman, both works 2018) shows a carp eating from a mermaid’s palm—lean against walls and columns in thick gold frames. Medusa (2016), in which a patchwork bust of a woman sits atop a wind-up box, evidences Chetwynd’s interest in automatons and toys, while the titular nod to an archetype of female grotesquery situates the artist in a lineage of feminist responses to Bakhtin’s carnivalesque. As Mary Russo suggests in The Female Grotesque (1995), masquerade, parody, and excess offer new forms of social subjectivity for women.2

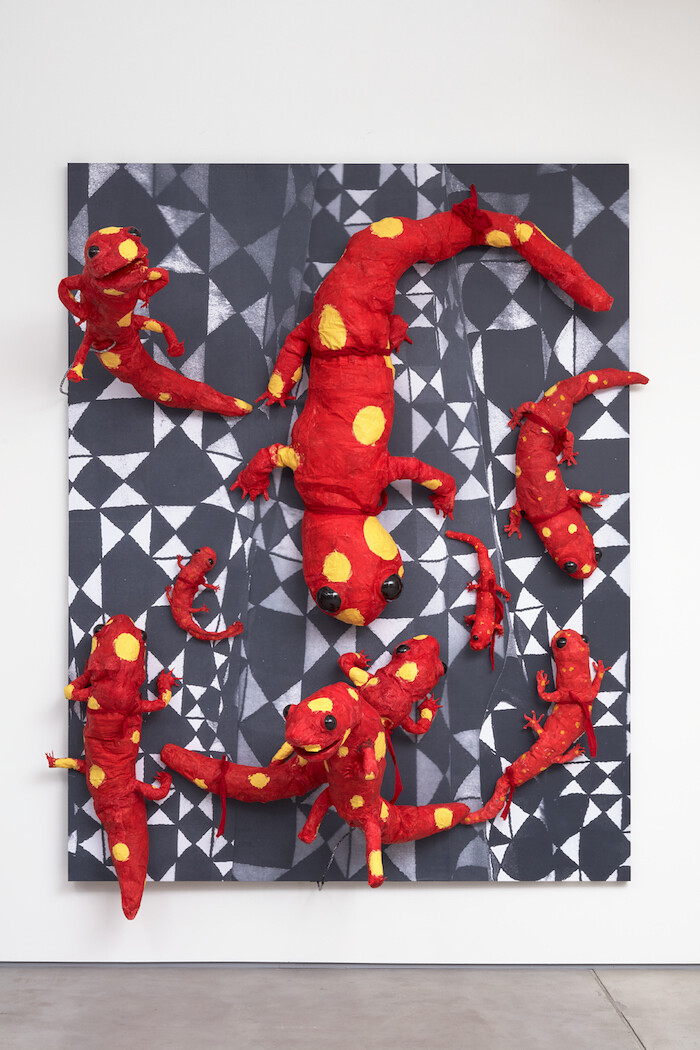

Chetwynd refers to the wall-mounted works as “paintings,” although the more immediate comparison might be assemblage. In each piece (all dated 2018), a digital print of an existing artwork—notably Richard Dadd’s hallucinatory painting The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke (1855–1864)—is pasted onto a wooden board, forming a backdrop for various objects, costumes, and props made from papier-mâché, torn fabric, and other basic materials. Animals abound. There’s a monstrous caterpillar, a wide-eyed group of red-and-yellow polka-dot salamanders, and a giant bat with a toothy grin protruding into the space like a gargoyle. It is all emphatically handmade.

Chetwynd’s use of “low” materials—kitchen roll, newspaper, photocopies, latex, paint, fake fur: the semiotics of the glue gun—reflects her embrace of folk plays, 1960s happenings, and DIY drag culture. These materials, which would not be out of place in a kitchen or child’s bedroom, also suggest that she is working within a particular tradition of performance that elides the distinction between public and private spaces, galleries and homes. (Chetwynd has cited as an influence Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who in her 1969 text Manifesto for Maintenance Art asserted: “Everything I say is Art is Art. Everything I do is Art is Art.”) The furry creatures in Cat People spill out of the picture and into the gallery space. Like the grotesque body, they are in a state of flux, of exceeding boundaries.

The qualities of recombination and transgression, both rooted in Chetwynd’s lifelong engagement with alternative communities, align her work with the anarchist thinker Hakim Bey’s concept of the Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ). As the artist and activist John Jordan writes in Beautiful Trouble (2012), a TAZ should “feel like an exceptional party where for a brief moment our desires are made manifest and we all become the creators of the art of everyday life.”3 At Sadie Coles, the desire to subvert and democratize—to throw an exceptional party—takes the form of irreverent digs at art history and the commercial market.

An appropriated reproduction of an ancient Roman fresco, Pompeian Wall (2018), has been papered over the entire back wall of the gallery in a deliberately tacky homage to trompe l’oeil: a made-to-measure photocopy. Like the gold frames, which are made from Dutch metal (a cheap imitation gold leaf), the spectacle—of history, of art, of art history—is an illusion. As with her live work, which Chetwynd has argued is too often interpreted as “willful amateurism,” this craft-based, ad-hoc aesthetic belies a deeper engagement with socio-politics.4 The amateur is a lover of labor, and often this labor exists outside of exploitative working conditions, or is pleasure-based. Amateur groups often self-organize, determining their own structures defies social norms. With this context, the title of the exhibition, “Ze & Per”—after the gender-neutral pronouns—can be read as an ode to the power of self-definition.

Mikhail Bakhtin, “Carnival and the Carnivalesque,” Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: A Reader (London: Longman, 1998), 250–9.

Mary Russo, “Carnival and Theory,” The Female Grotesque (Oxford: Taylor & Francis, 1995), 53–75.

John Jordan, “Temporary Autonomous Zone,” Beautiful Trouble (New York: OR Books, 2012).

Ben Eastham, “Interview with Marvin Gaye Chetwynd,” The White Review online (August 2013), http://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/interview-with-spartacus-chetwynd.