Some twenty years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China a proposal was made to change the traffic rules so that cars would stop at green lights and go at red, because red was the designated color of action. In the same spirit, citizens named their children after the roles they were to fulfill in the new China. Jianguo is one such name, meaning literally to “construct the country.” Liu Ding’s fictional persona for this solo show at Antenna Space was born just three years after the nation was established in 1949.

Liu Ding is both an artist and a curator. This double identity is clear from the first impressions of this exhibition, which appears as a tightly curated group show in which each work is part of a puzzle comprising the art world, state ideology, and “the West.” The walls of the gallery are divided into horizontal blue and white bands and the colorful tiles of the original floor left visible. The space is filled with more than 30 stylistically diverse selection of works; there are collaged photographs separated from their sources (Figures taken out of Context, 2015); realist, figurative paintings executed in a colorful palette (such as Li Jianguo, 2016); and two installations that look more like collections of evidence than the products of a process. All of this is orchestrated in an unorthodox and controlled architecture with plinths that are too tall for the viewer to comfortably see the sculpture it supports, and a low platform running along the wall to keep a distance between the viewer and the works, as in old-fashioned museums.

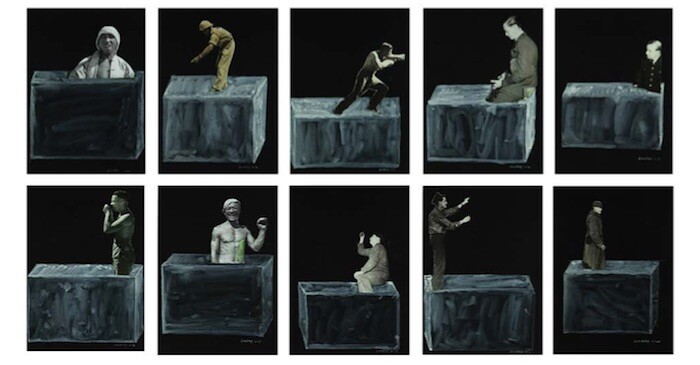

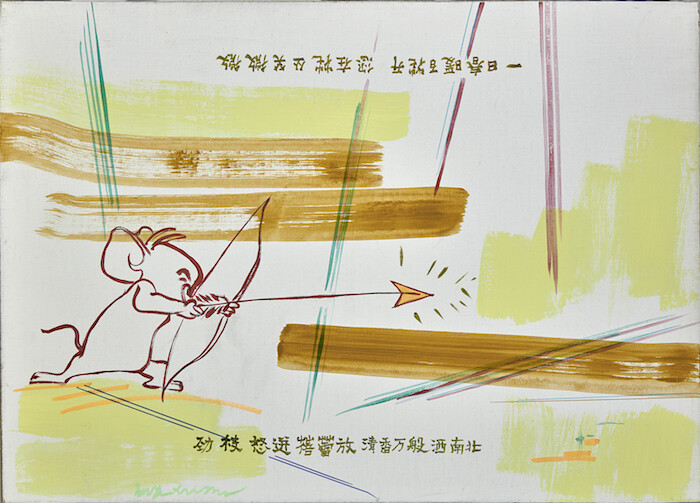

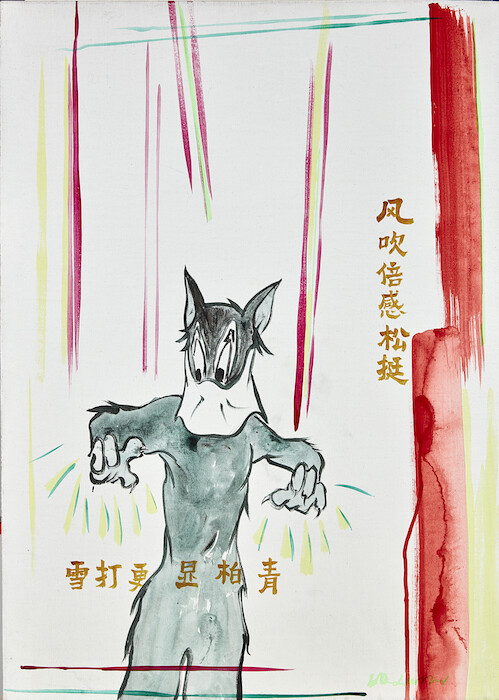

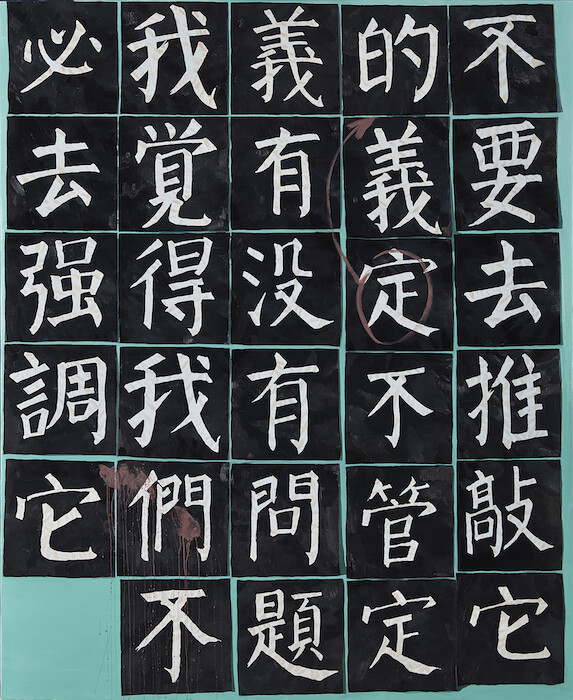

Liu Ding’s curatorial research with his collaborator and wife Carol Yinghua Lu took a new turn in 2010. Recognizing that China’s art history is often legitimated by comparison with Western art history, they decided to take a more self-reflexive approach and look at the roots of contemporary Chinese art by studying the legacy of Socialist Realism. Each of the works touches upon a sentiment that is present in Chinese society. Take the large oil painting Li Jianguo, which shows the backs of a naked, middle-aged man and woman. Either of them might be Li Jianguo, since the name is not gender-specific. They are walking towards a banner with an unreadable slogan and a golden fence of the type installed on Tiananmen Square after a man from a Uighur minority in Xinjiang province crashed his car into the Forbidden City near the portrait of Mao Zedong in October 2013. Other works link societal dynamics with what was happening in artistic circles. 1988 (Language As The Issue) (2016)—an installation in which colored booklets, a canvas, and bronze sticks seem to have fallen together—points to the aftermath of the 1985 New Art Movement, when a progressive momentum was halted by a debate between two factions within the group over language, and returned to a conservative stance. This was shortly before a crackdown on the arts, a phenomenon usually narrated through the closing of the legendary “China/Avant-Garde” exhibition held at Beijing’s China Art Gallery in February 1989. The series “Apolitical Figures” (2016), on the other hand, refers to a change in state ideology, when the Gang of Four was denounced after Mao’s death in 1976. The paintings feature cartoon characters Tom and Jerry and excerpts from the “Tiananmen Poems”—anonymous poems written at the time by demonstrators and posted in the public square—from which all terms related to commemoration and condemnation have been omitted. This act echoes the gesture of editing politicians out of state photographs after they fell out of favour, a common practice during the tumultuous Mao years.

Li Jianguo is not a fictional artist created for the show, as I first thought; s/he is a commoner, an average joe. “Li Jianguo Born in 1952” is also the title of a 1997 song by the Chinese band 43 Baojia Street, which describes Li Jianguo as a man who has a good life but can’t help feeling a bit lost. In 2016 he would be a 64-year-old who had lived through several revolutions, in a nation where slogan culture is still part of street life but feels dissonant with today’s capitalist reality. It is this twist of subjectivity that is most striking in the exhibition. Liu Ding extracts the individuality of the artist from the solo show but inserts the persona of Li Jianguo, who can stand for anyone in society. Featuring street banners and textbook slogans, the works function as witnesses to stories, a trait also present in Liu Ding’s earlier work (2012’s A Story Told to me by Wang Luyan, for instance, was an installation based on a tale about a work that Liu Ding never saw himself). In this case the stories seem to reveal how the leftovers of doctrine are navigated by different members of society, making universal values the subject of individual opportunism. Li Jianguo might represent the artist, the engineer, or the waitress: each of their choices are driven by mundane desires, but are dressed up in ideology.