Mejor Vida Corp

In 1998 the artist Minerva Cuevas launched an ingenious and complex ongoing economic fiction as a means of exploring the politics of contemporary hope: Mejor Vida Corp. (Better Life Corporation).

According to Cuevas, the project started more or less spontaneously around 1997, and derived from her interest in defying the structures of the art market by anonymously distributing small-scale art objects in public spaces. Later on, in the winter of 1997 to 1998, while traveling in the New York City subway system, Cuevas saw a poster produced by the train administration bearing the slogan “Awake is Aware,” warning the passengers against the dangers of falling sleep while traveling. To prevent passengers from having a “rude awakening” (the title of a film that was advertised at the time of the “Awake is Aware” campaign), Cuevas started leaving small bags with caffeine doses attached to the posters located in the cars, as if the subway administration were distributing them in the guise of “safety pills.” The more or less classical intention of defying the status of art as a commodity was replaced with the more radical intention of playing with the goal of achieving public good by means of art practice. The project was refined by the invention of a corporative identity. The company would experiment with an unheard-of modality of aesthetic and political intervention involving systematic acts of generosity purportedly fulfilling urgent demands from the public. According to the corporation’s motto, MVC works “for a human interface.”

Further mocking the structure of a private corporation, Cuevas rented an office on the 14th floor of the tallest skyscraper in Mexico City. From this local 1950s modernist icon, Cuevas designed a website that is part of the “irational.org” group, which also has contributors in England and Spain, (33) and set out to establish a whole range of products and services to be given away for free on request and with no obligation to reciprocate. MVC’s catalogue is a small compilation of contemporary dreams and antidotes to frustration. Cuevas leaves random “magic” seeds (very much in the tradition of Ben Vautier’s unlabelled cans of “mystery food”) next to ATMs, suggesting to the customer an agrarian turn to make money. She has tested people’s reaction to unexplained gifts by giving away subway tickets at rush hour in the Mexico City underground, saving travelers the long morning queues. On occasion she has discreetly volunteered to clean public buildings (including subway stations), to write letters for the illiterate, or to support small campaigns through disinterested voluntary work. Some of MVC’s products reflect the fears of the population, for instance providing tear gas for personal protection, or promising to provide security services to the population by applying (so far unsuccessfully) to join the police corporations in Mexico. Other products are more related to wishful thinking in general: MVC does not distribute money as such, but it can provide the customer with lottery tickets. Cuevas has made galleries such as Chantal Croussel in Paris extend letters of recommendation to people who might need them to apply for a job. Finally, there are those services which, despite seeming rather simple and cheap parasites of public or private services, entail quasi-criminal activity: MVC distributes prestamped envelopes, accepting full responsibility for their contents. Cuevas produces customized, trompe l’oeil bar code stickers (or “trompe l’scanner” as the artist says) to reduce prices of articles in the supermarket. So far the most successful and iconic of the MVC projects has involved the issuance of student ID cards that allow one to get the international student identity card and apply for discounts.

Reviews

“The Art of Minerva Cuevas Tackles Corporate Exploitation in the Food Industry” •

There are people who seem to have a special insight into their deepest motivations from a very young age. Such is the case of conceptual artist Minerva Cuevas. “It is precisely why I am an artist and why I am interested in art. This capability of art to generate culture, and of culture to have an impact in society,” she observes ….

There are people who seem to have a special insight into their deepest motivations from a very young age. Such is the case of conceptual artist Minerva Cuevas.

“It is precisely why I am an artist and why I am interested in art. This capability of art to generate culture, and of culture to have an impact in society,” she observes.

Minerva Cuevas was born in 1975 in Mexico City and studied Visual Arts at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas. Her career now spans more than two decades and many different mediums, such as painting, sculpture, photography, video, installations and performances. In addition, her work has been exhibited all over the world, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museo Jumex in Mexico City.

Although initially interested in pursuing a degree in literature or philosophy, she decided to study Plastic Arts, wanting to explore these disciplines through something a little more practical. Her aim was to embed art within our daily lives.

One of Cuevas’ first projects was the foundation of Better Life Corp (Mejor Vida Corp.). “I think with this project, the main focus was to respond to the urban context of Mexico City. So more than an ideology, it was this series of interventions and reactions to the urban context,” she explains. “Basically, I was interested in the products that relate to food and to somehow survive in an urban environment.”

In Mexico City, Cuevas gave out free subway tickets or barcode stickers to be used for fruit and vegetables at supermarkets, which would show a lower price when scanned. When the project was brought to Toronto, she distributed student ID cards so people could make use of discounts and other student benefits.

Her most celebrated pieces focus on criticizing corporate exploitation of natural resources and human labour. Ironically, she does so by using the companies’ own logos and advertisements as a starting point, reappropriating capitalist language to condemn exploitive practices.

By making just a few changes to these globally recognizable images, Cuevas grabs our attention and redirects it to the negative and less-publicized issues they represent. In this way, she promotes several of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals such as Responsible Consumption and Production, Decent Work and Economic Growth, No Poverty, and above all, Reduced Inequalities. Some of the companies she has featured are Fresh Del Monte, Hershey’s, Toblerone, Evian, McDonald’s, and more recently, Coca-Cola.

“I think that the connecting thread of all my work is related to social and political research,” she remarks.

With a playful yet sharp vision, Minerva Cuevas embodies art as protest and a source of change. She invites us to look closer at the products we consume and think about their real cost — the human lives behind them.

You can learn more about Minerva Cuevas’ work in her website and follow her on twitter.

“Minerva Cuevas Wants to Make Your Life Easier” •

Mejor Vida Corp, an exhibition at Hedreen Gallery, offers products and services for free. Above the receptionist the words “Mejor Vida Corp” are arched over a handshake graphic, emblazoned in silver vinyl on the wall. The receptionist asks if I would like a student ID card. She takes my photo with a Polaroid Instax, then meticulously crops it with…

Mejor Vida Corp, an exhibition at Hedreen Gallery, offers products and services for free.

Above the receptionist the words “Mejor Vida Corp” are arched over a handshake graphic, emblazoned in silver vinyl on the wall. The receptionist asks if I would like a student ID card. She takes my photo with a Polaroid Instax, then meticulously crops it with scissors, affixes it to a card with craft glue, stamps it in numerous places, and pushes it through a laminator. The card, she explains, is useful anywhere student discounts are offered. There’s my photo, next to the words Extensión Universitaria and estudiante t. completo—“full-time student.” I’m not a full-time student anywhere.

Mejor Vida Corp (“Better Life Corporation”), a project by artist Minerva Cuevas, distributes products for cheap or free, such as cleaning services, self-stamped envelopes, and subway tickets. At the current exhibition at Seattle University’s Hedreen Gallery, you can get a student ID card, QFC barcode labels for cheaper prices, or a personalized letter of recommendation. The receptionist, Hedreen gallery assistant Kelsey Siegert, writes me a letter on SU letterhead. Generic and pre-signed by Hedreen’s curator Amanda Donnan, whom I have never met, it reads that she has “been witness to [my] intelligence and competence.”

Minerva Cuevas is a conceptual social-practice artist who lives in Mexico City. Several of her works appropriate the language of branding and advertising for anti-consumerism purposes as a form of culture jamming. Donnan, who initiated MVC’s Seattle headquarters, tells me she was drawn to the project because “it offers everyone small ways to exercise agency and subvert the system through acts of micro-sabotage.” Since its start in 1998, MVC has issued thousands of student ID cards, subway tickets, and other services. Participants, of course, assume full responsibility for the use of these services. I ask Donnan about the potential risk to participants, and she says “there has not been any blowback in the 20 years MVC has been operating.”

To reach out to those who could benefit most from these services, Donnan advertised the show on Craigslist and for the opening hired a sign-spinner, who swirled a cardboard arrow outside the gallery: “Yes It’s FREE.” Donnan even worked with Moises Himmelfarb, cultural attaché at the Mexican Consulate in Seattle, who sent an announcement through its networks. “Himmelfarb said that the undocumented immigrants who come to the Consulate seeking assistance could benefit from MVC’s student IDs. Apparently many people want any form of photo ID they can get, and the Consulate can’t process them all.”

Social-practice art often blurs the lines between performance, activism, and community organizing, where artists often assume the role of social-service providers. MVC is reminiscent of Rirkrit Tiravanija’s seminal 1992 exhibition Untitled (Free) at 303 Gallery in New York, where he served visitors rice and Thai curry. The genre is hotly debated: While some praise its de-emphasis of art objects in favor of direct responses to social and political issues, others criticize it for putting an aestheticized spin on nonprofit work and reducing political organizing to a symbolic gesture.

Whether you agree that MVC meaningfully disrupts the transactional exchange, the exhibition is here if you want to save a bit on food or need a letter of recommendation for a job. And maybe that’s enough. The project, for Cuevas, is about the “latent possibility of revolt implicit in the everyday.” Her revolt involves devising ways to make our lives easier, in a society where people rarely give without expecting something in return.

“Igniting the Archive” •

The Mexico City–based conceptual artist Minerva Cuevas explores the ways in which seemingly banal items like fruit, chocolate, and water reflect the practices and ideology of global capitalism. She employs a wide range of forms, such as rebranding campaigns that subvert a corporation’s logo to reveal power…

The Mexico City–based conceptual artist Minerva Cuevas explores the ways in which seemingly banal items like fruit, chocolate, and water reflect the practices and ideology of global capitalism. She employs a wide range of forms, such as rebranding campaigns that subvert a corporation’s logo to reveal power dynamics and histories of colonialism, and artist-run organizations that emulate various real-world entities.

Cuevas has regularly exhibited in Europe and Mexico for some twenty years, but, aside from appearances in a handful of group shows over the last decade, her work has not been seen extensively in the United States. However, this fall, US audiences have an opportunity to look more closely at her practice. The artist is participating in the two-year, research-based initiative “Public Knowledge,” launched by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the San Francisco Public Library this past April. Cuevas was also invited to create a mural at the Dallas Museum of Art, where it will be on view from September 2, 2017, to February 11, 2018, and she is included in Prospect.4 in New Orleans. In addition, she has a two-week residency this September at the Kadist Art Foundation in San Francisco, which will lead to a show there in 2018.

Cuevas’s multipart “Del Montte Campaign” (2003–) responds to the corporate exploitation of natural resources in Central and South America. In exhibitions, the project has consisted of sculptural elements (grocery-store-style stacks of canned tomatoes with labels that read pure murder) and billboardlike murals. She alters the name of Del Monte Foods to “Del Montte,” a reference to José Efraín Ríos Montt, the president of Guatemala from 1982 to ’83, who used military strikes against the Ixil people, an indigenous Maya ethnic group. Montt was staunchly anti-Communist and, as a result, received support from the US, which shipped millions of dollars of military equipment to fuel a conflict that the UN has called genocide. One distinct strategy that he used to control the Guatemalan rural population was the social program Frijoles y Fusiles (Beans and Rifles). Those villages that the military deemed to be allied with the government received food while resisters were massacred. When we consider Guatemala’s history as a banana republic and US interventions into Guatemalan politics on behalf of the United Fruit Company in the 1950s, Cuevas’s “Del Montte Campaign” highlights the geopolitical intersections of food, state actors, and corporations, as well as the racist violence perpetrated against indigenous communities for both profit and political power.

Cuevas established the Mejor Vida Corp. (Better Life Corporation) in 1998 in Mexico City as a kind of umbrella organization for projects like the “Del Montte campaign.” Initially renting an office on the fourteenth floor of the Latin American Tower, a modernist architectural icon that is one of the tallest buildings in the city, Cuevas offered free services, such as sweeping up debris in public spaces, and products, like subway tickets and barcode stickers to reduce the prices on goods from grocery stores.[1] She drew her first clients from the people who came in and out of the building to conduct business. Art world iterations of the Mejor Vida Corp. have appeared at the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City, Z33 in Belgium, and the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. In those contexts, the participants were museum visitors. In the case of the Museo Tamayo, Cuevas requested that the museum allow free admission. Institutional officials refused, but one of the Mejor Vida Corp.’s services is to print student ID cards, enabling visitors to get free entry to the museum.[2] Another campaign listed on the organization’s website critiques Mexico’s national lottery for serving private interests. In posters and murals, Cuevas disrupts the red heart of the lottery logo with bloodlike drips and the text en méxico 46,000,000 de personas viven en pobreza (In Mexico 46,000,000 people live in poverty).

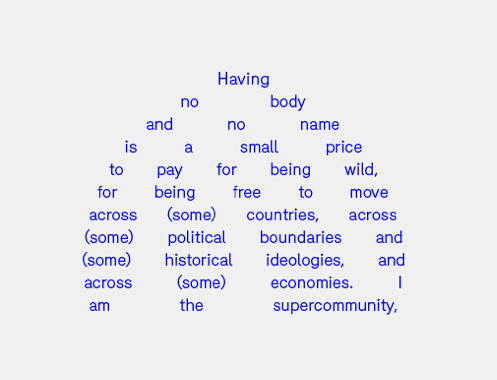

Does the Mejor Vida Corp. intervene in everyday life or is it a conceptual gesture that has no practical application?[3] Cuevas has insisted that it is not ideologically motivated activism. For one reason, she intends the website to emulate for-profit businesses. It also has a very limited capacity, and it does not advocate for an explicit set of ideals. Artist Tania Bruguera, however, includes the project in her online archive Arte Útil (Useful Art) because of its practical effects for the user.[4] At the same time the Mejor Vida Corp. functions like Walid Raad’s Atlas Group, in that it exists through the labor of one person but implies a collective effort, turning the organization into a representation of collectivity.

Particular qualities of collectivism and collaboration differ from one artist-run organization to another, but these entities are in many ways predicated on resisting the traditional dynamic of the artist as an active creator and the viewer as a passive consumer.[5] For the collectivist work to exist, there must be some sort of social interaction between at least two people. In Cuevas’s case the collaboration starts with the participant asking for a student ID card and continues through its every use.

Unlike the Mejor Vida Corp., Cuevas’s International Understanding Foundation (IUF), structured like an institution mandated to serve the public good, features a mission statement and a board of trustees. It began in 2016 as her contribution to a group exhibition at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, where it consisted of an architectural space resembling a three-dimensional Mondrian grid painting arrayed with various items. There were archival photographs of a 1980s punk-band performance in which the backdrop was a 1920s social-protest graphic depicting workers in blocky black-and-white shapes with the text tag der freiheit (day of freedom).[6] She paired Warhol’s disaster painting 129 Die in Jet! (1962) with its source, the front page of the June 4, 1962, New York Mirror, thus underscoring how an artwork can traverse the border between the real and the symbolic. Cuevas also included a rock she was given by Jimmie Durham as a gift and a Mickey Mouse figurine holding a piece of white paper bearing a quote from Bertolt Brecht: what happens to the hole when the cheese is gone? She collaborated with a composer in Cologne to write an iuf hymn, which was performed by a choir made up of administrators at the Museum Ludwig. Together, the installation wove a tapestry of social and political narratives that moved in and out of popular and more rarefied forms of culture.

The IUF can fit into different contexts, and Cuevas plans a presentation of it for her exhibition with the Kadist Foundation in 2018. This show will also draw on her research for “Public Knowledge.” Organized by SFMOMA’s Deena Chalabi, Dominic Willsdon, and Stella Lochman, “Public Knowledge” addresses recent shifts in the Bay Area resulting from the technology industry boom and how those changes affect cultural memory.[7] The boom has led to rising socioeconomic inequality, pushing families from their traditional communities and pricing out cultural spaces.

For “Public Knowledge,” Cuevas has undertaken a residency at the San Francisco Public Library. Her work there is both an investigation into an archive and an engagement with the civic structure that maintains the archive. The primary theme of her research is fire, which is a paradoxical element, given its threats and benefits.[8] She considers it a metaphor for revolution, flames being one visible manifestation of social protest. But fire poses a threat to libraries, notoriously destroying the ancient Library of Alexandria in Egypt in several blazes between the first century bce and the seventh century ce. On the other hand, the technology to start and control fire contributed to the natural and cultural evolution of the earliest human communities. Cuevas is also interested in the idea that fire, like information, spreads, and the spread of information is what underlies San Francisco’s technology boom. In this sense, there is an inverse relationship between the destructive characteristics of fires in the Bay Area—the 1851 fire that destroyed almost a quarter of the city or, more recently, the 2016 Ghost Ship fire in Oakland—and the ways that technology has metaphorically ignited economic development.

Cuevas examines how various social forces use images, leveraging and activating them to achieve their goals. For instance, the “Del Montte” project riffs on the way that advertising communicates visually with a consumer. But activism, the dissemination of countercultural resistance, also depends on images, which are put forth in rallies, marches, mass mailings, and the media. Cuevas knows this well since she has been documenting these forms of activism with her long-term project Disidencia (2008–), a video archive of protests in Mexico City. Protests often rely on performativity and visuality and thus are forms of representation. In this sense, Cuevas both reveals and implements the political power of images.

Endnotes

[1] To my mind, these documents are acts of civil disobedience, pushing up against the limits of legality. I have never heard of Cuevas or any of her clients being arrested for using her items.

[2] Interview with Minerva Cuevas by Hans Ulrich Obrist, July 24, 2001, nettime.org/archives.php.

[3] The notion of political efficacy is hotly contested regarding socially engaged art practices. One example of this debate was sparked by Ben Davis’s essay “A Critique of Social Practice Art: What Does It Mean to Be a Political Artist” in the International Socialist Review, July 2013. The response, which started on social media and then was facilitated by the nonprofit Blade of Grass through a series of blog posts (to which I was a contributor), was published in Public Servants: Art and the Crisis of the Common Good, ed. Johanna Burton, New York and Cambridge, New Museum and MIT Press, 2016.

[4] For more on Arte Útil, see www.arte-util.org. According to the website: “The notion of what constitutes Arte Útil has been arrived at via a set of criteria that was formulated by Tania Bruguera and curators at the Queens Museum, New York, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, and Grizedale Arts, Coniston, UK. Arte Útil projects should: propose new uses for art within society, use artistic thinking to challenge the field within which it operates, respond to current urgencies, operate on a 1:1 scale, replace authors with initiators and spectators with users, have practical, beneficial outcomes for its users, pursue sustainability, and re-establish aesthetics as a system of transformation.”

[5] Among noteworthy artist-run institutions that engage the politics of everyday life are e-flux’s Time/Bank (2009–), which proposes an alternative economic model based on the exchange of time and skills; Women on Waves (1999–), an organization founded by activist physician Rebecca Gomperts that provides abortions in international waters, outside the jurisdiction of countries in which the practice is outlawed; Tania Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International (2010–), an advocacy organization for immigrant rights; Rick Lowe’s Project Row Houses (1993–), which offers art, education, and social services to Houston’s Third Ward; and Theaster Gates’s Rebuild Foundation (2010–), a platform for neighborhood transformation on Chicago’s South Side.

[6] Interview with the artist, Dallas, May 2017.

[7] In addition to Cuevas, artists Burak Arikan, Bik Van der Pol, Josh Kun, and Stephanie Syjuco are participating, as are scholars Julia Bryan-Wilson, Jon Christensen, Teddy Cruz, Fonna Forman, Jennifer A. González, Shannon Jackson, and Fred Turner.

[8] Interview with the artist, Dallas, May 2017.

“Minerva Cuevas: The Construction of Reality” •

Minerva Cuevas thoroughly exemplifies what it means to be a “citizen of the world” in the contemporary moment. Constantly on the move from city to city, her work processes arise out of temporary residencies in specific locations, during which she delves into collective histories, marginalized or hidden by official…

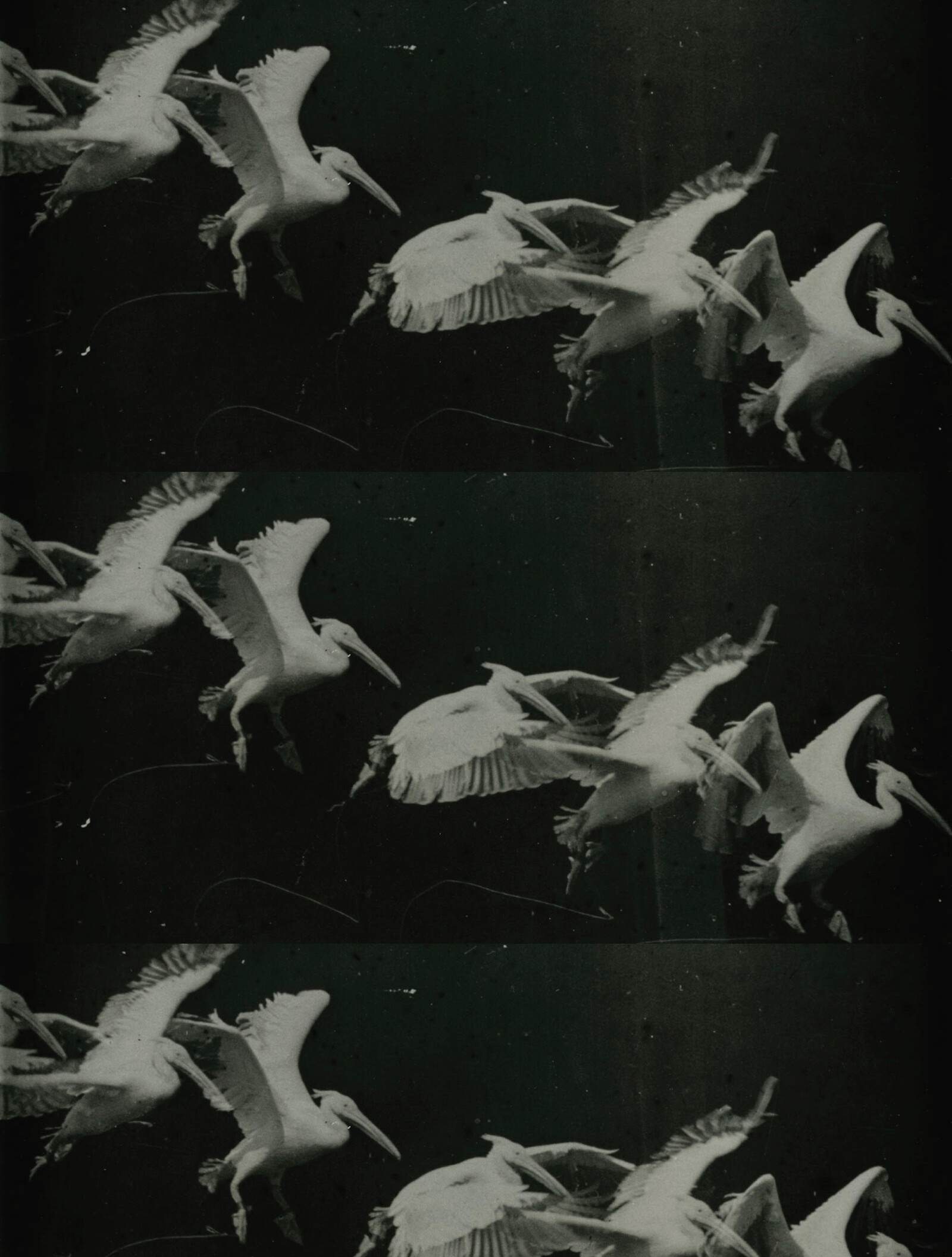

Minerva Cuevas thoroughly exemplifies what it means to be a “citizen of the world” in the contemporary moment. Constantly on the move from city to city, her work processes arise out of temporary residencies in specific locations, during which she delves into collective histories, marginalized or hidden by official narratives. Her practice is born out of two fundamental lines of questioning: the first has to do with the mechanisms for the distribution of images and their epistemological function; the second with the configurations—both collective and organic—of community in the broadest sense. This goes beyond mere geographic coincidence and even transcends it; in addition, the forms of representation she selects play a fundamental role. Communities of animals constantly appear in the work of this artist as allegories for models of connection in human societies.

Her first experimental interventions began with the project Mejor Vida Corp. (Better Life Corp.), starting in 1999 in Mexico City; an ironic simulacrum of a corporation which offered services—anti-profit and quite generously—that consisted of an array of products to endure the dynamics of life imposed by capitalism, especially for those without any capital: student photo ID’s to get discounts in movie theaters and museums, letters of recommendation for jobs with the name of the corporation to whomever requests one, bar codes to replace the labels at grocery stores to get discounts on food, metro tickets handed out at rush hours. With all services, it is always very clear, of course, that the corporation is the one offering the services and thus ensures their “market presence.”

Minerva Cuevas’ work questions the role images play in the construction of reality…

Cuevas grounds her work in this logic, uncovered through her research on different North American agricultural corporations operating in Latin America—whose history of imposing exploitation and consumption in several of these countries has been kept more or less hidden. Cuevas begins to co-opt the logos, labels and publicity posters from important multinational companies’ products, using their potential for expedited communication and conserving their recognizable elements, although she does minimally modify their contents. In this way, she is able to synthesize and use disguises in order to make clear a series of historical events that have favored the expansion of these corporations, but which would never be mentioned in a media campaign. An example of this work can be found in the mural Del Montte, 2003, which refers to the United States involvement in the coup against Guatemalan president Jacobo Árbenz. It also references the relationship between several North American politicians and the United Fruit Company which was able to establish a monopoly on bananas—just to mention one such monopoly—in several Central American countries, thanks to CIA participation. Terra Primitiva, a mural presented at the Sao Paulo biennial in 2006, describes an episode in the fierce struggle of companies like Cargill and Monsanto to acquire the patents to vernacular species developed in the Amazon.

In addition, Cuevas attempts to highlight the affinities between different collectivities that go unnoticed and invest them with a sense of community by means of exercises calling for these linkages to be recognized. Concierto para Lavapiés (Concert for Lavapiés), 2003, is the result of a newspaper ad directed at street musicians interested in participating in a spontaneous jam/concert in the Lavapiés neighborhood in Madrid; its population is presumably fifty percent immigrant. Although at first it was scheduled to last thirty minutes, the influx of musicians and the enthusiasm unleashed caused it to go on for more than an hour. The event was documented in a series of photographs and a video. Her most recent intervention consisted of putting a coin into circulation— S·COOP, 2009—among the merchants of Petticoat Lane in East London. This currency is only accepted at Monochrome, an ice cream shop and temporary documentation center exhibiting the history of the neighborhood, which was a center of textile production and where an immigrant population—first Jews, then Bengalis—has lived and worked.

The exhibition Phenomena, presented in 2007, took its name from the Kantian distinction between the realm of appearances, reality filtered by human perception and affected by point of observation (phenomena), and the realm of things in and of themselves, the real-real, what is knowable only through reason (noumena). The artist projects a series of film fragments onto the walls of the exhibition halls; this footage is from scientific experiments from the beginning of the Twentieth Century, as well as several slides of animals in captivity and in the process of being domesticated. A series of microscopes in the same area also function as projectors, showing lenses whose amplified images seem to have emerged from a kaleidoscope. The antiquated slides of these images seem to be an attempt to return to us to that other “point of view,” and from that different vantage point (phenomena) sketch out a notion of time.

The fundamentals of contemporary science have their origin in observations of daily transformations. Several of Minerva Cuevas’ works enact a kind of homage to those perservering observers who tried to anticipate natural phenomena in order to document them. People like the Swiss biologist Moisés Bertoni who went to the Paraná and decided to stay there to study its species for the rest of his life, or Stanislav Lem, a doctor and an academic who left a record of his concerns about the possibility of communication with another kind of civilization in several futurist and philosophical novels and stories, Solaris being the most well known.

Minerva Cuevas’ work questions the role images play in the construction of reality and her objective is to return us to a moment before the image when experience and observation could still be differentiated. And in the midst of the accelerated development of technologies designed to dominate and invent certain sections of the world at the cost of the others, and in which knowledge is a mere instrument for these ends, this artist transports us to those destinations where the act of doing science— and I would say also the act of doing art—is an attempt to understand the world in order find a better way to inhabit it.