e-flux video rental

Conceived by Anton Vidokle and Julieta Aranda in 2004 as a video rental shop that operates for free, e-flux video rental was a project proposing an alternative means of distributing and circulating video art. In spite of the fact that many artists of the 1960s and 70s were drawn to working with video because it was relatively inexpensive and easy to reproduce and distribute, the subsequent assimilation of video art into the precious-object economy of the art market has significantly limited access to video works.

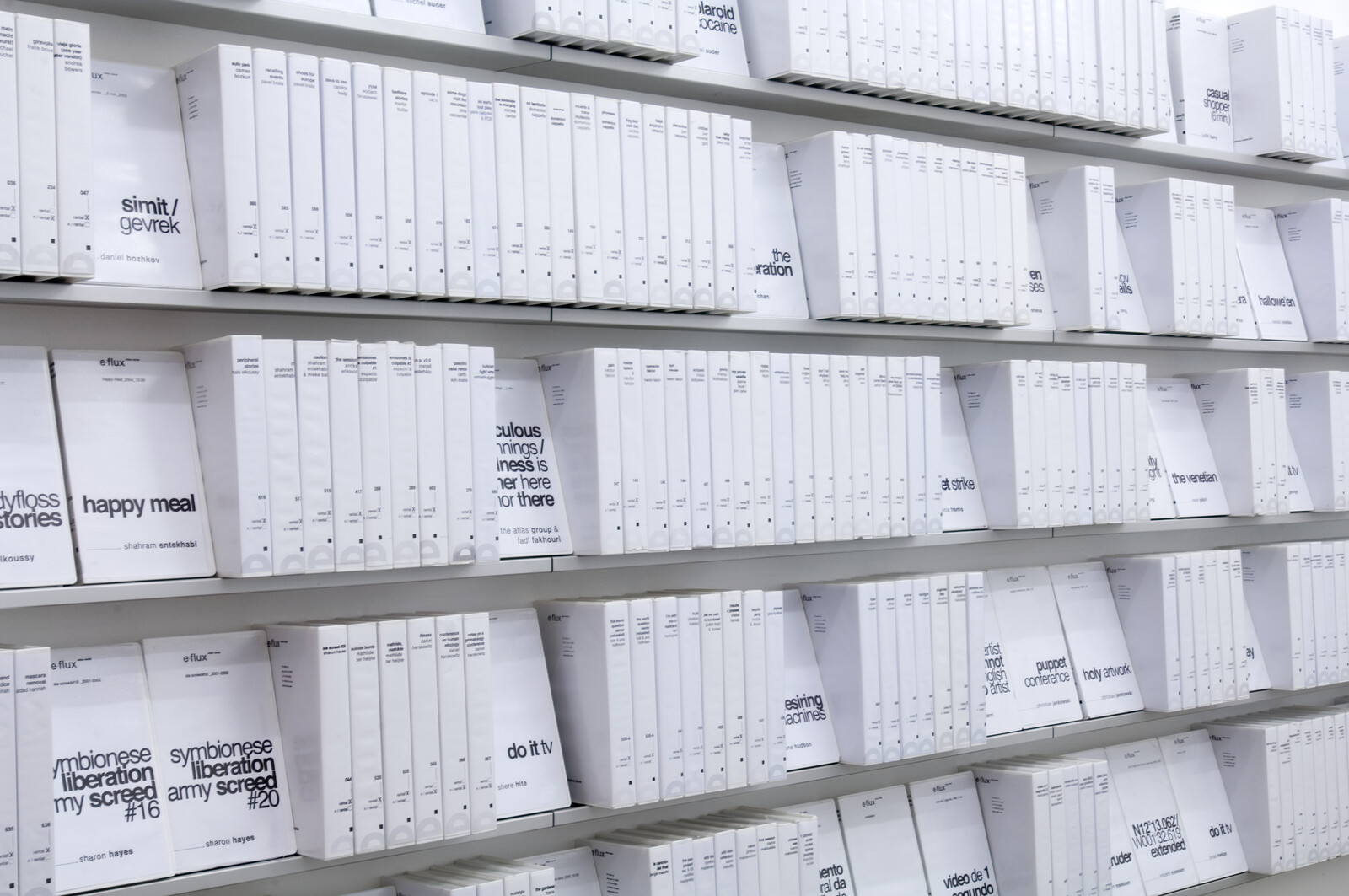

EVR began as a functional reflection and inversion of this process. Comprising a public screening room, a film and video archive that grew with each installation of EVR, and a free video rental shop, VHS tapes could be watched in the space or checked out and taken home once a viewer has completed a membership form.

Since its original presentation at a storefront at 53 Ludlow Street in New York in 2004, EVR traveled to venues in Amsterdam, Berlin, Frankfurt, Seoul, Paris, Istanbul, Canary Islands, Austin, Cali, Budapest, Boston, Antwerp, Miami, Lisbon, Lyon, and Rome. Each time EVR was presented in a new city, local artists, curators, writers, and art historians were invited to select works to be added to the collection. Over the years, this resulted in a collection of nearly 1000 works of film and video art by more than 600 artists and artists’ collectives from all parts of the world, until it finally found a permanent home in the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Ljubljana in 2011.

e-flux video rental at e-flux, New York, 2004

Screening event part of e-flux video rental at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany, 2005

Screening event part of e-flux video rental at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany, 2005

Opening night of e-flux video rental at Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2005

Lecture part of e-flux video rental at Arthouse, The Jones Center, Austin, Texas, 2006

Anton Vidokle at e-flux video rental at Centre Culturel Suisse de Paris, Paris, France, 2007

e-flux video rental at I Bienal de Canarias, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain, 2006

e-flux video rental at Centre Culturel Suisse de Paris, Paris, France, 2007

e-flux video rental at unitednationsplaza, Berlin, Germany, 2006

e-flux video rental at Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2005

e-flux video rental at e-flux, New York, 2004

e-flux video rental was shown in the following venues:

e-fux, New York, NY, 2004

Artprojx Cinema Series, Prince Charles Cinema, London, UK, 2004

Insa Art Space, Arts Council Korea, Seoul, South Korea, 2005

Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2005

KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany, 2005

Manifesta Foundation, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005

The Moore Space, Miami, Florida, 2005

I Bienal de Canarias, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain, 2006

Arthouse at The Jones Center, Austin, Texas, 2006

PiST///, Istanbul, Turkey, 2006

unitednationsplaza, Berlin, Germany, 2006

Mucsarnok, Budapest, Hungary, 2006

Location Project, Antwerp, Berlgium, 2006

Extra City Center for Contemporary Art, Antwerp, Belgium, 2006

9th Lyon Biennial, Lyon, France, 2007

Centre Culturel Suisse de Paris, Paris, France, 2007

Carpenter Center, Boston, Massachusetts, 2007

the building, Berlin, Germany, 2008

Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal, 2008

41 Salòn Nacional de Artistas de Colombia, Cali, Colombia, 2008

Fondazione Giuliani per l’arte contemporanea, Rome, Italy, 2010

MG+MSUM, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2011

Reviews

“EVR: e-flux video rental” •

Arthouse at the Jones Center, through Jan. 7 At a time when we all might have thought that video rental was becoming passé, taken over by online video streaming and Netflix, the self-described “New York-based information bureau” e-flux presents a joint opening of three such rental locations in Austin, Istanbul, and the Canary Islands. An…

Arthouse at the Jones Center, through Jan. 7

At a time when we all might have thought that video rental was becoming passé, taken over by online video streaming and Netflix, the self-described “New York-based information bureau” e-flux presents a joint opening of three such rental locations in Austin, Istanbul, and the Canary Islands. An interesting assortment of apparently unrelated choices, to be sure … which is something that might initially be said of the e-flux video rental (EVR) project itself, since its video holdings snowball from city to city as area curators add their favorite and often obscure pieces of video art to the EVR mix. But while it may seem random to have Austin curators such as Risa Puleo and Annette Carlozzi contribute any films they choose to the project as part of its two-month stay at Arthouse, it does in fact serve a real purpose: EVR was conceived by e-flux as a collaborative enterprise, and contributions from every site where it’s stationed broaden the number of participants in the project, just as the movement of sites and librarylike policy of “renting” the videos – in short, it’s free – ensures an ever-expanding audience of viewers. This ongoing expansion creates a dynamic map of contributors and participants that mirrors our own culture of increasingly inter-netted lives. With a simple sign-up process and a notecard membership, all of us sign our names into e-flux’s own reconfiguration of the networks we embody on a daily basis.

But EVR is much more than that as well: For interested viewers who aren’t ready to commit to the two-day return policy, EVR offers on-site TV/VCR combos that bring back all the best trappings of video rental culture. In fact, just after choosing between the cushy couch or the beanbags, I was quickly reminded why those “please rewind” stickers were used by so many video stores. The films are arranged in alphabetical order by artist, and a numbered guide to the collection lets you pick out films based upon who recommended them. After grabbing Carlozzi’s pick of “Saberverv&etilde;encias,” I sat down to screen “Hello, Ms. Schnitt.” With Austin’s EVR located just inside the glass front of Arthouse, watching this terrific five-minute flick by Corinna Schnitt was a double experience of both viewing and being viewed. Friendly and curious smiles of passersby reminded me that Arthouse’s window serves as a screen itself. As more and more lunch-goers passed the building and glanced inside, one stopped to ask, “What is this place?” While the gallery attendant had a helpful answer, I wondered how she could honestly begin to explain that this art gallery, currently Austin’s EVR, was a chance not only to see some very interesting, hard-to-find pieces of film and video art in what was once an emerging technology but also to participate in a study of our own patterns of communication – of information flow and networking by immersion. It is a chance to check out of the world around you, and into it, all in the very act of renting or viewing a film.

“Emulsion to Emulsion” •

The term “emulsion to emulsion” has somehow stuck in my head from my undergraduate days, taking courses in photography. It is the phrase meant to remind you of the placement needed in order to expose a negative correctly: place the side that received the light down against the top face of the paper, also the light sensitive side. This…

The term “emulsion to emulsion” has somehow stuck in my head from my undergraduate days, taking courses in photography. It is the phrase meant to remind you of the placement needed in order to expose a negative correctly: place the side that received the light down against the top face of the paper, also the light sensitive side. This is one of those phrases that may stick around – for the sake of scanning images, let’s say – but it will no longer bare any logical relationship to the original technical process, like using the “CC” field of an email, or hitting “shift” on a computer keyboard.

I started thinking about this because I have been working for the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles to archive and organize her past projects. Mierle Ukeles has been an artist since the sixties, becoming well-known with her performances involving the city of New York City’s sanitation workers. She participated in the recent exhibition WACK! and has been canonized as a feminist artist of a certain generation. As I scan the only slides of these performances and other ephemeral works long-gone, I say to myself, “emulsion to emulsion.” This not only reminds me to place the piece of film the correct way in the scanner, but it also orients the slide in the same way it was held in the camera while capturing these past moments.

The slides I’m scanning for Mierle Ukeles are older than I am. There is an implied history in this process, but clearly “photography” is changing. I see more than a simple quantitative shift in our experience of photographic images. It is not just that there are more images and that they are easier to produce, but that images exist with the status of some vestigial agnomen, photography in name only, which relies on the premise that “photography” once existed.

Image reproduction on the Internet has become a runaway phenomenon. It is widely understood as the largest threat to copyright law, but it sounds hyperbolic to say that the Internet alone has changed photography. (For the record, most reproductions on the Internet are protected by Fair Use precedents thanks to 2 Live Crew.) In the case of documented performance and ephemera, the concern about the sanctity of images is very real, but it is complicated by the very impulse that photography can also aim to dismantle the art object.

By now I’ve come to accept that the art of something sometimes lies beyond the thing itself. I’ve found this in my experience documenting and archiving for other artists as well as in my recent role as an intern for the e-flux video rental on Essex Street in the Lower East Side. Working with the extensive and growing catalog of videos, I have been responsible for insuring the continued life of the material, in all different formats, for the sake of this organic archive and exhibition. This has amounted so far to little more than copying “disk images” – another linguistic vestige derived from the “image” – onto a hard drive. This little image of a disk essentially emulates the commands of the DVD as well as the information stored on it. The immaterial image here has come to represent a set of functions to be carried out.

Much like that other use of the latin-derived “flux,” the projects at e-flux utilize the potential for enactment, the change possible through many iterations of representation. Both in their journal—which opts for a print-on-demand model—and in the e-flux video rental, the definitive physical form is not so much rejected as it is perpetually deferred. Through many reproductions one actually ensures the life of what is essentially there, which we know is not what is really there so much as it is the functions to be carried out. I’m reminded here, and with archiving generally, that truly the best way to ensure something carries on into the future is not to worry about protecting it, but rather to let it live, to copy it, reproduce, ensure its procreation. In the end, that sounds pretty human.

“Swap Shop” •

One of the unfortunate ironies of video art is that a medium which originally developed out of democratic desires has become the most tightly controlled of all contemporary art forms. Pictures of paintings are circulated in photographs, but in an era of rapid digital reproduction, gallerists and collectors are wary of allowing videos out of their sight….

One of the unfortunate ironies of video art is that a medium which originally developed out of democratic desires has become the most tightly controlled of all contemporary art forms. Pictures of paintings are circulated in photographs, but in an era of rapid digital reproduction, gallerists and collectors are wary of allowing videos out of their sight. Simple good business demands maintaining scarcities; master copies are accordingly watched like Fort Knox. As a result, video artists often lack access to the work of their colleagues – a fact which perhaps goes some way to explain the extreme variation in artistic quality which still plagues the medium. E-Flux Video Rental (EVR) aims to address this condition. Organized by Anton Vidokle and Julieta Aranda’s international art organization e-flux, the scheme extends the pair’s interest in alternative models of art circulation by providing a free art video rental service along with a public screening room and a small art book library. Originally started as three travelling caravans the enterprise now incorporates two permanent branches – one in e-flux’s headquarters in Manhattan’s Chinatown, and a second in the back of an East Berlin supermarket. The third, which remains in transit, is currently to be found in Cali, Colombia.

EVR enlists local curators to source video art pieces from gallerists, most of whom, appreciating that more immaterial forms of economy are also at work in the art world, are happy to oblige. A DVD is dispatched, transferred onto video tape, and sent back. In this way, the scheme avoids directly challenging commercial power structures, to instead negotiate an alternative space within them.

The use of obsolete technology is important here. On the one hand, the choice is tactical: an analogue video is less easily copied than something in digital format, and so allows dealers to retain some security. On the other hand, there is also a tacit expression here of the under-notated topic of media ecology. Given forms of technologies nurture particular social patterns; with the advance of new technologies, these may be overrun. The return to the devices and formats of yesterday is thus something like the establishment of reserve parks for endangered species: an action worth undertaking to preserve threatened milieux.

EVR’s Berlin branch organizes regular weekly screenings as a means towards both expanding their archive and introducing a social element into proceedings. The programme on the evening of Thursday 11 December played-off against the general idea of the project in an interesting way. Curated by Florian Wüst and assembled around the theme of electricity, with particular stress on Doug Aitken’s name-making video installation Electric Earth(2000), the five pieces shown each explored the connections between space and the media, belief and technology, information and bodies.

Aitken’s evocative work centred on the breakdancer Ali ‘Giggi’ Johnson, moving eccentrically through a desolate urban landscape. Beginning with shots of Johnson slumped in front of a television with a remote-control in his hand, the work implants a strong suggestion that the subsequent scenes of the film, which feature no other actors besides Johnson himself, might amount to a media-generated hallucination. ‘A lot of times I dance so fast that I become what’s around me,’ says Johnson early on, ‘I absorb that energy […] it’s like I eat it. That’s the only now I get.’

In orbit around Electric Earth were four lesser known efforts. The first of these, Franciszka and Stefan Themerson’s Polish short The Adventure of Good Citizen (1937) initially recalled – to my uncharitable mind – an episode of The Simpsons in which Krusty the Clown loses the rights to The Itchy & Scratchy Show and is forced to screen a baffling Eastern European equivalent in its place. Packed with clusters of extreme close-ups, the Themersons’ plot turns on a collective effort to stave off the apocalypse through the absurdist tactic of rigorously walking backwards. This, from a Polish film made in 1937, was undeniably historically pithy.

In the wake of this madcap extravaganza, Lotte Schreiber’s film quadro (2002), composed of still shots of Modernist architecture conjoined with guitar noise courtesy of architecture-film-soundtrack-specialist Stefan Németh, came off as sterile. By contrast, the location material which comprised Neil Beloufa’s documentary Kempinski (2007) – centred on the technological animism of a group of farmers in Mali – seemed to sprawl quickly beyond the director’s control.

The final video of the night, Maja Borg’s Ottica Zero (2007), was also the most directly relevant to EVR’s own concerns. Fusing together the theories and models of the futurist guru Jacque Fresco (founder of ‘The Venus Project’, c.1975-ongoing) with the possibly fictionalized story of the Italian movie actress Nadya Cazan, who elected one day to become a wandering mystic, the film presented two different approaches – one utopian, the other ascetic – to constructing alternative social models in the contemporary moment. More modest and limited than either of these, EVR’s own line seemed to me more strategic. The next screening, organized around the themes of ‘Home’ and ‘Alone’, is scheduled for Thursday 18 December.

“Blockbuster Art” •

The storefront at 53 Ludlow Street on the Lower East Side looks like a standard, if exceptionally clean, video store. But don’t expect to find a “Lord of the Rings” special edition; the shelves hold tapes by video artists. E-flux Video Rental is the first real-world project of Electronic Flux Corporation, an online venture operated by the artist-curators…

The storefront at 53 Ludlow Street on the Lower East Side looks like a standard, if exceptionally clean, video store. But don’t expect to find a “Lord of the Rings” special edition; the shelves hold tapes by video artists. E-flux Video Rental is the first real-world project of Electronic Flux Corporation, an online venture operated by the artist-curators Anton Vidokle and Julieta Aranda (www.e-flux.com). The artworks in their growing inventory are available for free two-day loans (in low-resolution VHS format, to discourage misuse). The store, scheduled to close in March, currently features nearly 500 works, lent by more than 340 artists. Here are the 5 most frequently borrowed titles so far.

1. “An Artist That Speaks No English Is No Artist,” Jakup Ferri, Kosovo(2003, five minutes). Mr. Ferri tries to tell a story in English that is broken beyond repair. As his frustration increases, familiar-sounding words give way to gibberish.

2. “The Nuclear Football,” Korpys/Löffler, Germany (2004, 30 minutes). Using press credentials, the artists filmed a 2002 state visit to Germany by President Bush and tried to capture images of the black briefcase holding nuclear-missile launch codes that always travels with the president. Instead they exposed elaborate stagecraft and security preparations otherwise invisible to the public.

3. “A Bit of Matter and a Little Bit More,” Lawrence Weiner, United States(1976, 20 minutes). An experimental pornographic film, shot at P.S. 1 in Long Island City, featuring Mr. Weiner’s trademark enigmatic texts superimposed on close-up footage of three pairs of unidentified but recognizable curators having sex.

4. “Do you know anything about Polish Art?,” Hubert Czerepok, Poland(2002, 15 minutes). People on the streets of various European cities are asked that question, with predictably negative results.

5. “From My Window,” Jozef Robakowski, Poland. (1978/1999, 20 minutes). A record of more than 20 years of changes to the public square in front of Mr. Robakowsi’s apartment in Lodz.

“February 2009, Anton Vidokle” •

The name of the previous project in that space was untiednationsplaza - a subversively glamorous translation of a street (square) name, Platz der Vereinten Nationen. That was the name for Anton Vidokle’s “exhibition as school”, which he had conceived after Manifesta 6, where he was appointed a curator, was cancelled. Restless as a…

The name of the previous project in that space was untiednationsplaza - a subversively glamorous translation of a street (square) name, Platz der Vereinten Nationen. That was the name for Anton Vidokle’s “exhibition as school”, which he had conceived after Manifesta 6, where he was appointed a curator, was cancelled. Restless as a revolutionist should be, instead of curating he created. In collaboration with over a hundred of artists, writers and theorists unitednationsplaza existed as an informal, open, and free arena for thought exchange, available to all.

Linguistically, the building is a more humble, if not direct approach to the architectural structure of the present project, located in that same indescript cube attached to the back of a supermarket. Keep in mind too, that Platz der Vereinten Nationen is just a square of land in the midst of East Berlin’s typical residential architecture. When I first arrived at the door, I stayed at the door. For about an hour nobody was answering the buzzer or the telephone. Do not be discouraged: it could only mean that the place is free of institutional rigor.

Once inside I was welcomed warmly and told that I could basically do whatever I wanted, that is rent the videos, or watch them on site, as well as grab some publications to read. The current function of the building is e-flux video rental, an extensive archive of freely available video art selected by curators and artists, and a reading room filled with art publications and art magazines from all over the world. In other words, a continuation of unitednationsplaza in the form of a database.

What we are witnessing is a unique initiative for self-fueled discourse, backed by visual and written material available on site. Importance of such gesture is more than critical. The sole purpose of making art is to communicate. With ever changing trends and market driven strategies of commercial art venues it becomes hard to follow artistic practices from all over the world. Another case lies in the roots of video art itself – many artists turn to it for low cost and easy access, but copyrights and distribution procedures prevent a broader audience from accessing the source material. Even with some material available online the building remains an unprecedented act.

Exhibition without discussion is all but worthless, but it seems to be the status quo of most events in the art world. Anton Vidokle goes further, turning an exhibition into a school one more time and giving up the role of a mentor. What matters most – especially in digitized reality – is the space itself. With a friendly, unpretentious and deinstitutionalized atmosphere the building provides a venue for unexpected meetings, spontaneous discussion and most importantly free education.

Appreciated or not, manufacturing of new artworks will remain futile until they are self-sustainable and able to provide fruitful and unrestricted conversation. The artist as producer must yield to those able to utilize available and still unexploited resources, rich in potential and ready to use. Now is the time.

“Web Review: E-flux” •

THE field of contemporary art has, in the past century, seen the extensive development of various enabling and entrepreneurial organizations. I’m speaking here of the spectrum of exhibition venues, critical journals, various supporting service industries, public relations firms, and so on that now constitute an expanded landscape of a cultural production…

THE field of contemporary art has, in the past century, seen the extensive development of various enabling and entrepreneurial organizations. I’m speaking here of the spectrum of exhibition venues, critical journals, various supporting service industries, public relations firms, and so on that now constitute an expanded landscape of a cultural production system more tolerant of new forms than new social relations among its constituents. Such structures are the natural consequence of a field whose reach and operational tempo, like that of many others, has increased significantly with the proliferation of global telecommunication systems and the concurrent fertility of entrepreneurial interests. Many of these facilitating structures then come regularly under scrutiny in the field’s more reflective moods—the programming tendencies of a museum, for instance, or the editorial inclinations of a well-circulated journal become rich topics for critical assessment and discussion. And yet there remain other organizations that seem somehow deliberately missed, like so much unexamined sinew of a field that is at every opportunity proclaiming its own self awareness and critical muscularity. How then to begin an assessment of such an organization? And furthermore, why?

The e-flux project has, for over a decade now, functioned as one such primary agent that is often, save for its perennial presence in the electronic inboxes of cultural workers around the world, largely invisible. The popular art press likewise reflects this by not reflecting. E-flux’s daily activities are the electronic distribution of texts—oftentimes press releases and institutional communiqués—from a large but exclusive group of clients and friends. And yet, somehow, it has evaded both attention and scrutiny—due in no small part to its virtuality. But, likewise, it remains a project that is greeted continually with what seems like a persistent misreading: that as an enterprise whose use value trumps the agency it so regularly exhibits and deploys.

Let’s begin then with something like a sketch of a few practical, generally understood things. E-flux as an entity originates in 1999, at a time when Anton Vidokle joined with artist colleagues and organized a one-night exhibition in a hotel room in New York’s Chinatown. The announcement for the exhibition was sent via email to a network of friends and associates, and subsequently forwarded and redistributed by its recipients. It circulated as information tends to circulate on the Internet: that is, with a mushrooming quality. The exhibition was thus well attended, and remains at the center of e-flux’s originating story. What continued from this modest beginning was a growing mailing list and a steady stream of announcements—exhibitions and events, primarily—distributed electronically. Subscription to this list was and remains free and publicly accessible. The distribution of texts to the list, however, was and is not. By all appearances, what seems to have been emerging at the time was a new media apparatus, arriving at a historically opportune moment on an Internet still lacking many of those edifices that now point back to the social and material relations of the world in which the network remains inextricably embedded.

What e-flux went on to became however was not this. More broadly speaking, the project is today an ongoing and evolving collaboration between its central protagonists, artists Anton Vidokle and Julieta Aranda, and an international cadre of cultural producers that have for many years now collectively authored an ambitious and expansive set of projects, provocations, texts and manifestations operating with and against the currents of commercially or institutionally specific art production, exhibition, and its partnering critical outlets. The organization from its beginnings signaled the arrival of a new type of networked knowledge production or distribution. I use these two terms—production and distribution—because it is precisely here, in the new immaterial sphere of activity, that they might interestingly begin to be contested or confused. That e-flux’s originating principle was as a distributor or aggregator of content is certain, but the organization has since gone on to produce various collaborative projects. An early example would be Rob Pruitt’s 1999 project “101 Art Ideas You Can Do Yourself” and the similarly spirited “Do It” book edited by Hans Ulrich Obrist and published in collaboration with Revolver five years later. Most recently, the 2008 launch of the e-flux Journal, a monthly online publication of cultural theory and artist’s projects, has again affirmed the double-pronged organization’s role as producer.

Of all the possible ways to think through or around the organization, this is perhaps the least interesting. E-flux has, by way of its endurance and taxonomical ambiguity developed something of a vogue institutional brand founded on the most non-institutional of platforms. To read even an excerpt of the company’s clients is to recognize some of the world’s most visible and powerful contemporary art institutions. Following this, e-flux commands material resources beyond its own communications capacity, and deploys them appropriately: the production, sometimes alone and sometimes partnering with other organizations or backers, of artist projects, some already mentioned in the previous paragraph. In this freedom to produce, to associate, and to do so without being beholden to any single institution is where collective autonomy finds its realization: not in some ideal future or imagined scenario, but right now, in New York, in Berlin, and elsewhere, too. The projects produced which somehow model or enact this form—an architecture of facilitation to communications or delivery—become especially interesting. Vidokle and Aranda’s E-flux Video Rental (EVR) project, for example, is at once a free and functional video rental, screening room, and a growing film and video archive. When installed, it functions as an aesthetic system based as an easily accessibly bank of popular culture moving towards obsolescence (the video rental store) on the one hand, and a useful (but controlled) distribution point for artist’s video on the other.

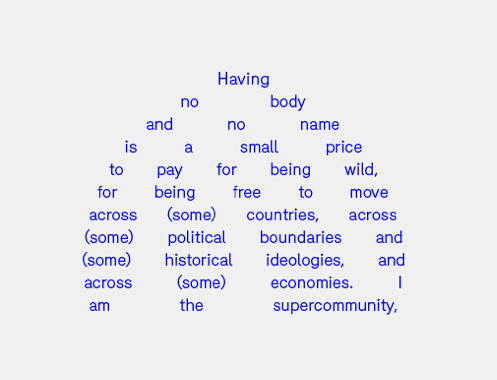

To evoke again, perhaps precariously, the language of architecture—a mode of analogy not uncommon in the field of information technology and networked computing—what we are discussing here is less an abstracted edifice designed and overseen by two artists, so much as a structural facilitator of the production, distribution and consumption of knowledge and information. It wouldn’t take more than a glance to the digital horizon to recognize this model operating outside of the field of contemporary art. It is everywhere finding new audiences and uses in the world of networked media and the content-driven Internet. We see it in the social networking sites whose developers create unobtrusive database interfaces and allow users to author the content that adds value to the site and attracts additional users. We see it also in media sharing sites like Flickr and YouTube, themselves a kind of conceptual approach to developing mass media: If you build it, they will come.

Much ink, to utilize a humorously outdated turn of phrase in the present discussion, has certainly been spilt on theorizing these late approaches to networked computing. They invite this sort of theorizing because they move so strongly in the direction of transparency, intuitive human interfacing, and a ubiquity that withstands the temperamental fashions of Internet usage. Most of all, they purport to a kind of denied agency: so long as no copyright or legal content issues be raised, they only serve the user her own data. To develop such a structure with an agency—a politics!—requires an affirmation of distributive or editorial control. It is the type of control we witness in the realization of the E-flux Video Rental previously mentioned, under the direct stewardship of its eponymous founding organization. The clearly oppositional orientation of that project to the popular mode of art video distribution as the editioned work is both a driving concept and an opportunity for the production of something between an aesthetic experience and a useful if temporary exhibition venue.

It is the same control we see in e-flux’s daily operations: subtle, perhaps, but certainly present in the select relationship with clients and the distribution of materials. Think, for instance, of the occasional atypical communication that makes its way to subscribers: Albert Hetta’s June 2005 announcement of a Kosovar Pavilion at that year’s Venice Biennale or a February 2008 news item on the financial capsizing of a very particular Lower East Side pawnshop. The organization’s politics emerge in these details, as they do in each production that bears the mark of their collective authorship. Just short of allowing one’s eyes to slip out of focus, e-flux begins quickly to resemble something like an art project. Or, rather, a cosmopolitan platform for enacting such projects. In this sense it is not unlike the abstract discursive platforms we find in the work of artists like Liam Gillick (by way of sculpture) or Rirkrit Tiravanija (by way of the kitchen)—both of whom have also extensively collaborated with Vidokle and Aranda. The difference between art as discursive platform and a project like e-flux is, of course, that the former is oftentimes embedded within a functional art exhibition context, while the latter many times exhibits no need for such things.