February 19, 2010

the cook liked to believe that his story pivoted on a parable about the relative merits of fact and fiction in everyday class struggle.

—from Allan Sekula’s This Ain’t China: A Photonovel (1974)

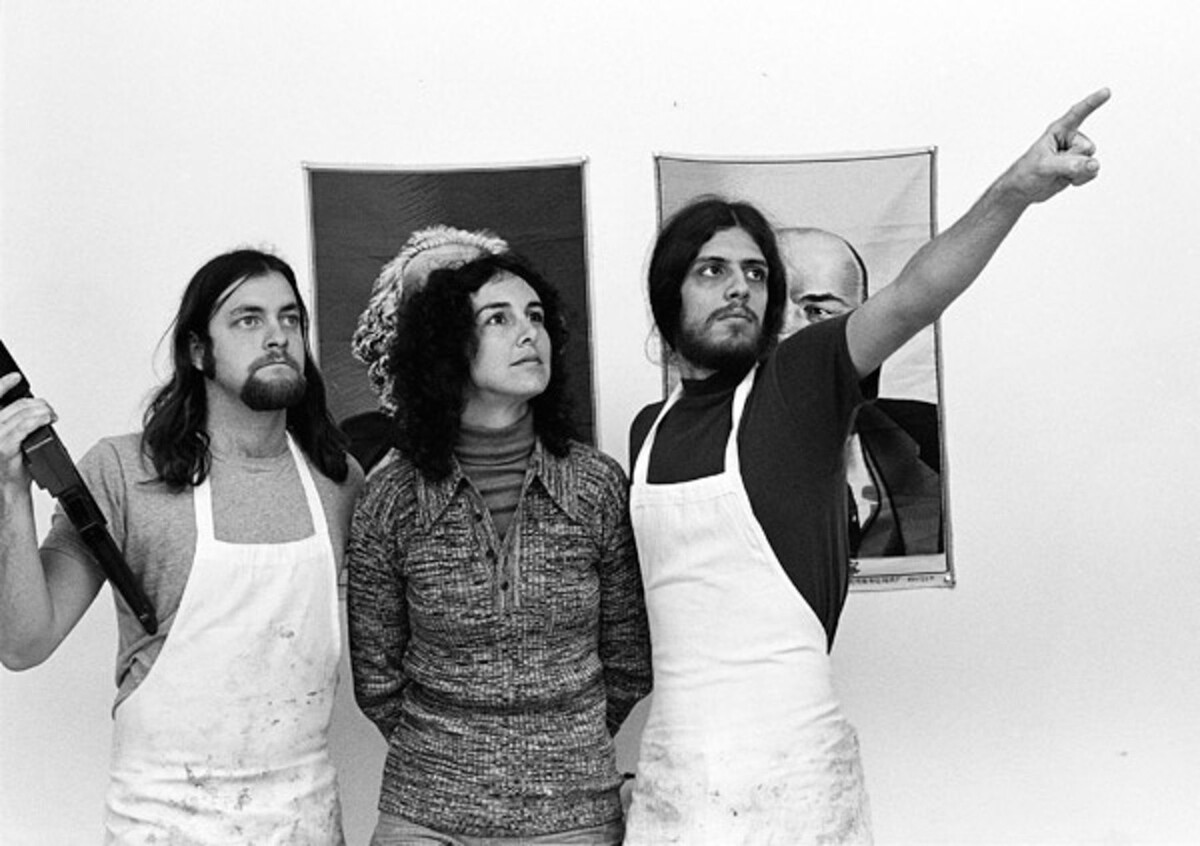

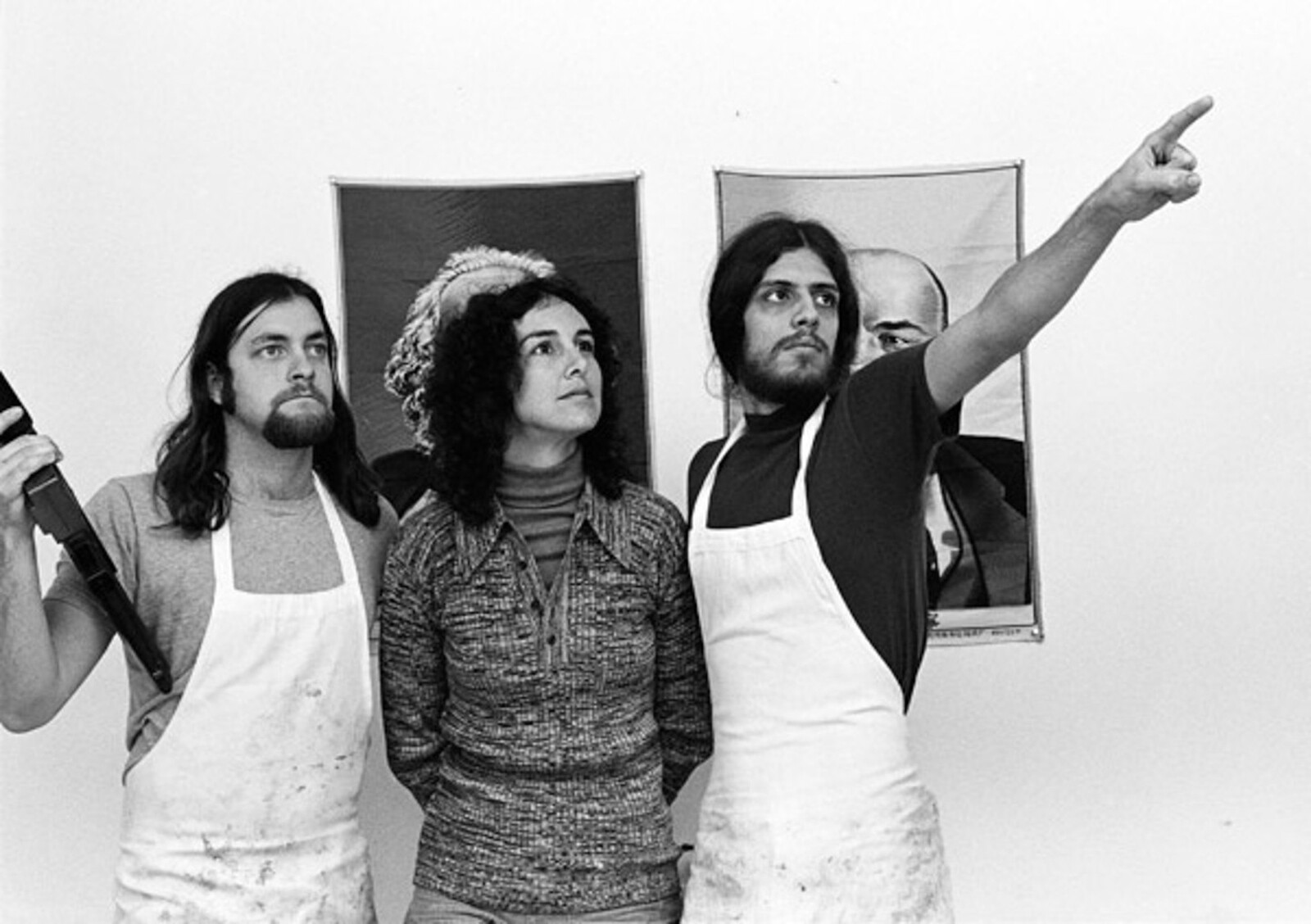

Allan Sekula’s 1974 photo-text work, This Ain’t China: A Photonovel, announces the artist’s early attention to China as a foil for Western paradigms of production—cultural and economic. The work combines a (meta)narrative with staged photographs, shot in the spirit of Jean-Luc Godard (in a Maoist phase and channeling Bertolt Brecht). Sekula’s plot concerns the employees of a greasy spoon restaurant in San Diego (artist included), all musing about working and living conditions, and plotting a strike—a microcosm implicated in a global imaginary, transformed by the presence of a different culture. This Ain’t China was made at a time of great interest—especially amongst left-leaning Western artists and intellectuals—in the possibilities of Maoism. Yet the counter-example of China, and its negation, remain elusive. In the ambiguous way it is evoked, China could be both the country at the height of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and fine dinnerware (porcelain or “fine china”).

Presenting the work in 2010 raises the question of how both these Chinas—as well as today’s People’s Republic, with its (ever enigmatic) embrace of capitalist manufacturing and consumption with a communist face—continue to configure imaginaries of alternative forms of production. Sekula’s 1974 photonovel is paired with a new work: a backlit transparency made for the storefront window of the e-flux space on Essex Street in New York’s Chinatown. The image was captured while the artist was doing research in one of China’s “special economic zones” near the port city of Guangzhou for a forthcoming documentary on working conditions in and around the world’s most active ports. It shows a young Chinese factory worker holding part of a kitchen appliance she is helping to manufacture, her eyes closed. The image may be seen as evidence of Sekula’s shift from staged photography to a documentary approach, and opens a question concerning the artist’s paths to realism. And yet the new image shares an element of refusal with the earlier photonovel.

A solo-show of two works, This Ain’t China: A Photonovel (1974) and Eyes Closed Assembly Line (2010), thus enables the visitor to trace key trajectories for Allan Sekula’s entire practice. The investigation of his special interest in China leads to other questions concerning the politics and aesthetics of working class refusal, what we might call an “attitude of ain’t.”

This Ain’t China is open to the public from Tuesday through Saturday, 12–6 pm at 41 Essex Street, lower level.

Allan Sekula is an artist whose innovation of photographic practice and theory centers on the engagement of documentary and performative forms in a sustained critique of economic, social and cultural globalization. He has exhibited extensively in the context of large-scale international exhibitions, including documenta 11 and 12. In 2003, Performance Under Working Conditions, a major retrospective exhibition with a publication on his work was organized by the Generali Foundation in Vienna. Currently a selection of works spanning the artist’s career, including early works and a new series, have been brought together in Polonia and Other Fables, which tours to The Renaissance Society in Chicago; Zacheta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw; Museum Ludwig in Budapest and Belfast Exposed.

Monika Szewczyk is a writer, editor and some-time curator based in Berlin and Rotterdam, where she is head of publications at Witte de With, Center for Contemporary Art. Her collaboration with Allan Sekula, focusing on This Ain’t China: A Photonovel, continues in the Summer of 2010 when the photonovel and a selection of new photographs will be featured in the group exhibition Nether Land (Act VIII of Witte de With’s year-long multi-part program with the leitmotif of ‘morality’), which will be presented in the context of the 2010 World Expo at the Dutch Culture Center in Shanghai.

A conversation between curator Monika Szewczyk and the artist will be held at The Cooper Union on February 22, 2010 at 6:30pm with free admission.

For further information please contact taraneh [at] e-flux.com.

Reviews

“Allan Sekula”, Magenta Magazine • Charlene K. Lau

Fittingly placed in e-flux’s Chinatown space, Allan Sekula’s most recent exhibition pairs his 1974 photo-text work, This Ain’t China: A Photonovel , with the new light box, Eyes Closed Assembly Line (2010). I already contemplate these two Chinas without delving into the artwork: the Cultural Revolution and the manufacturing powerhouse. The distance…

Fittingly placed in e-flux’s Chinatown space, Allan Sekula’s most recent exhibition pairs his 1974 photo-text work, This Ain’t China: A Photonovel, with the new light box, Eyes Closed Assembly Line (2010). I already contemplate these two Chinas without delving into the artwork: the Cultural Revolution and the manufacturing powerhouse. The distance between these Chinas is inhabited by Sekula’s career and an ongoing interest in work as art, and late capitalism.

In a time when much of contemporary art is humdrum and made by the overeducated middle-class, Sekula remains poignant with This Ain’t China: A Photonovel. Drawn to labour activism and working-class struggles, he worked in a generic fast food restaurant, documenting exploitation and discontent. Text, and a diagram of customer satisfaction and labour division, share the space with photographs taken in four styles. Glossy and plastic-y colour shots of delicious-but-sickly crinkle fries, pizza, salads and desserts have become antiquated, retro-looking to our 21st Century gaze. These products are accompanied by black and white images of their production: graceful, cinéma vérité candids of the workers at task. In other photographs, the same workers — a waitress, the cook and Sekula — assume revolutionary poses, signaling change and revolt, and contrasting the back-lit, crime-inducing and seedy suburban shots of the restaurant boss’s office and home. Are the workers going to strike? They reasonably could because, after all, it ain’t China.

Through five chapters, the accompanying text reads as what curator Monika Szewczyk calls a “Brechtian enterprise”: a theatre stage for making strange. The employees of the restaurant play characters, each of whom become confused ideologically. To compound the confusion, the text is written in all lower case. The uncapitalized “china” becomes ambiguous in its usage: is Sekula purposefully confounding the porcelain and the country? One’s meaning concerning the capitalist impulses of the newly wedded bourgeois and the other an intensely doctrinal country whose anthem was at the time “March of the Volunteers.” The two C/chinas could not be more disparate, and the possible contrasts in the work are largely left unresolved. What is this China?

The new China is reflected in the work Eyes Closed Assembly Line displayed in the window. An assembly line worker looks to be caught in a reverie while in the daily grind of her monotonous task. It is so monotonous, she can do it with eyes closed. While the light box glows effervescently in the evening sky of New York, the worker looks world weary, and with little interest in what lies ahead for the new China. Perhaps it’s because she doesn’t really have a choice, and even the brightest of lights cannot keep her awake in anticipation of change.

Sekula’s last line in his photonovel reads: “beware: a worker’s defeat has been converted into an artwork.” In a rare case in our contemporary circumstances, this art is indeed authentic protest. Aware of its own guile, Sekula’s protest is for the ongoing legitimacy of the worker’s plight.

—February 9, 2010