April 12, 2011

e-flux is delighted to present an exhibition of works by Gustav Metzger conceived by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Anton Vidokle following the exhibition “Gustav Metzger: Decades 1959-2009,” curated by Julia Peyton-Jones, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Sophie O’Brien at the Serpentine Gallery in 2009.

Born in Nuremberg, Germany in 1926 to Polish-Jewish parents, Metzger was evacuated to England as part of the Kindertransport in 1939. For 60 years, Metzger has practiced as a vehemently political artist and activist, with work spanning from the conception of auto-destructive art and the production of political manifestos to the initiation of strikes against consumerist markets, including the art world and the airline industry. Taking up art, politics, ecology, science and technology, Metzger critiques capitalist, industrialized society and systems of control, reflecting his discerningly adept perception on the rapidly changing world, contextualized by his experience of some of the twentieth century’s most devastating events.

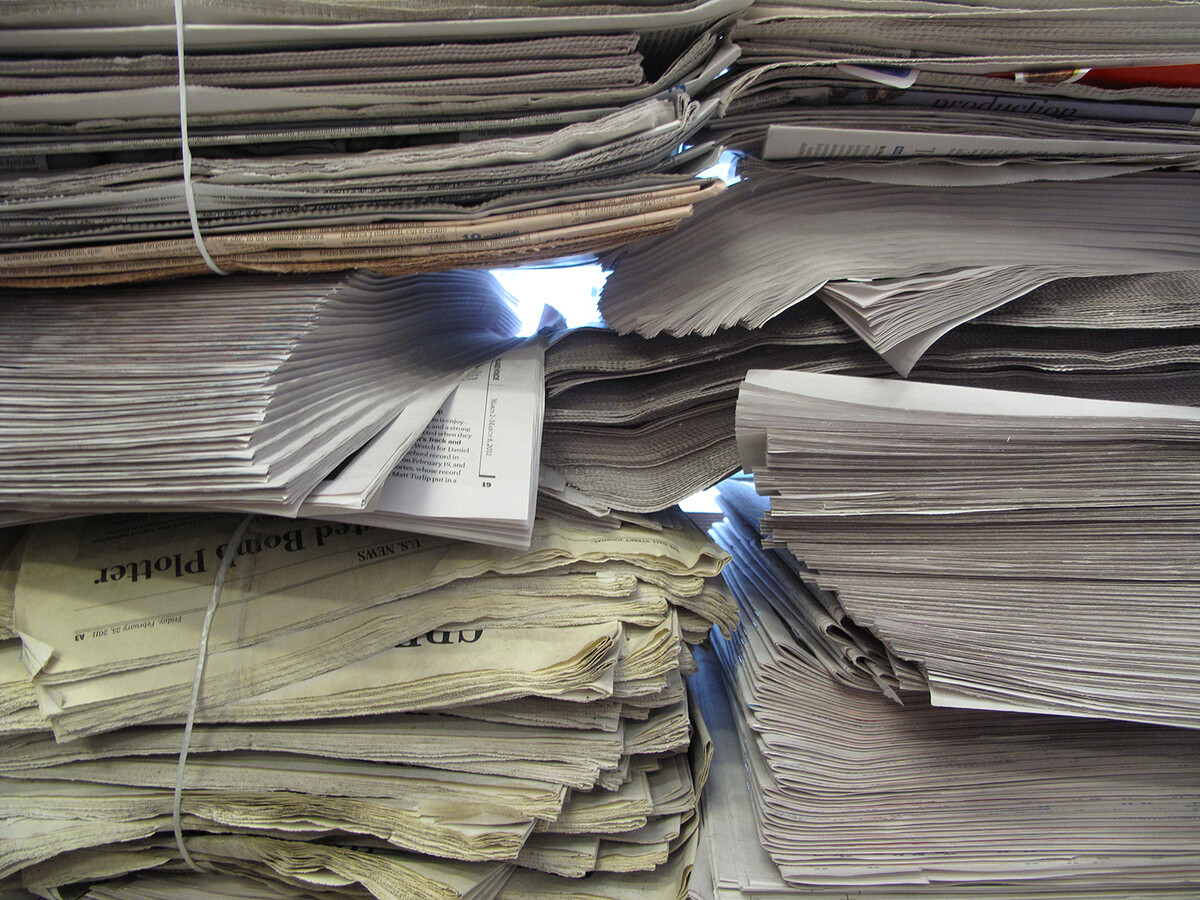

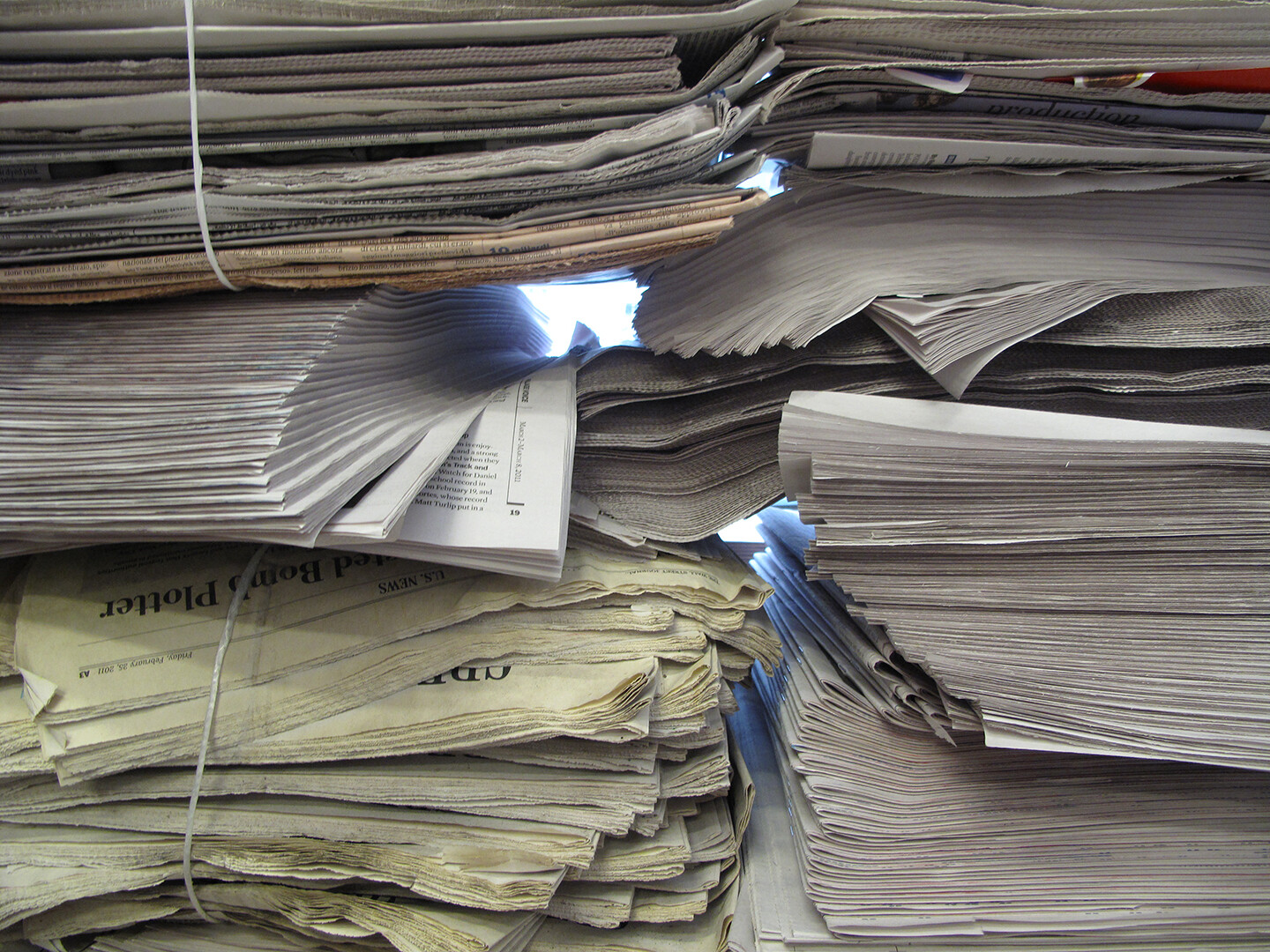

Two key works will be on view: MASS MEDIA: Today and Yesterday (2011), and Historic Photographs: To Walk Into – Massacre on the Mount, Jerusalem, 8 November 1990 (1996/2011), both part of the Historic Photographs series in which the artist responds to the media’s persuasive yet inadequate documentation of traumatic events throughout history. In MASS MEDIA: Today and Yesterday, (2011), thousands of newspapers are stacked in a rectangular mass in the middle of the e-flux project space. The viewer is invited to cut out articles related to the topics “credit crunch,” “extinction,” and “the way we live now” from local daily newspapers and display these on a wall. Addressing the capitalist consumption of goods and information that in turn threatens the planet’s ecological survival, the work suggests an endless collective expression of political disenchantment.

In Metzger’s ongoing Historic Photographs series, enormous reproductions of newspaper photographs—of the Holocaust particularly and more recent events such as the Vietnam War—are often obscured by a physical barrier of curtains, bricks or rubble. The uncomfortable intimacy and distorted perception of the original photograph makes it impossible to see in its entirety. To Walk Into – Massacre on the Mount, Jerusalem, 8 November 1990, (1996/2011) is a black and white image from the Italian newspaper l’Unità, taken at Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem during the Temple Mount massacre in Jerusalem on November 8 1990. The newspaper remains a central motif of Metzger’s work, asking us to challenge the obtrusive media presence in society. It embodies the tension at the core of Metzger’s practice: the use value of science, technology and politics as tools for societal progression, versus their criminal disintegration of the natural world and ethical tendencies.

Gustav Metzger’s work has most recently been exhibited in “Modern British Sculpture” at the Royal Academy, London, the 2011 Sao Paulo Biennale, and the XIV International Sculpture Biennale of Carrara. He has held solo exhibitions at the Serpetine Gallery, London; Zacheta National Gallery, Warsaw; Westfalischer Kunstverein, Munster; Lunds Konsthall, Sweden; and the Generali Foundation, Vienna. Metzger’s work was also included in the 2009 Tate Triennial, the 2008 Yokohama Triennial; and the 2007 Skulptur Projekte Münster. Metzger lives and works in London.

Special thanks to Laura Barlow (Exhibitions Curator, e-flux), Leanne Dmyterko (Assistant to Gustav Metzger), Mike Gaughan (Gallery Manager, Serpentine Gallery), Barbara Meneghel, Gustav Metzger, Sophie O’Brien (Exhibitions Curator, Serpentine Gallery), Julia Peyton-Jones, (Director, Serpentine Gallery) and Lorraine Two (Executive Assistant to Hans Ulrich Obrist, Serpentine Gallery).

For further information please contact mila [at] e-flux.com.

Reviews

“Gustav Metzger: Bad News Bearer at e-flux, a Veteran Political Artist Finally Gets His First New York Solo Show”, The Village Voice • Martha Schwendener

Gustav Metzger’s first solo show in New York is a modest affair. You climb down an iron staircase at e-flux to a basement room where a couple dozen stacks of newspapers resemble a scruffy take on the Minimalist cube. Against one wall is a small table holding disheveled newspapers and pairs of scissors. Above that is a printout that reads, “Please browse…

Gustav Metzger’s first solo show in New York is a modest affair. You climb down an iron staircase at e-flux to a basement room where a couple dozen stacks of newspapers resemble a scruffy take on the Minimalist cube. Against one wall is a small table holding disheveled newspapers and pairs of scissors. Above that is a printout that reads, “Please browse through the newspapers on the table, cut out articles that fall under the categories ‘Credit Crunch,’ ‘Extinction,’ and ‘The Way We Live Now,’ and place them on the wall.” A long, black magnetic board on another wall is filled with newspaper clippings.

The other work in the show is a black-and-white photograph—a blurry reproduction, actually, printed on white vinyl—that dominates a wall in the upstairs office. Taken at the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem during the Temple Mount massacre in November 1990, the image was originally published in an Italian newspaper and shows two armed soldiers standing over people—corpses, wounded, or captured, it’s hard to tell—lined up on the ground. In the foreground, a man who’s raised himself up slightly gazes toward the camera.

The work in the office is from Metzger’s Historic Photographs series, which will be shown at the New Museum next month, the artist’s first solo show in a U.S. museum. I only point this out—two first-New-York-solo shows in the space of a month—because Metzger is 86 years old and just had a retrospective at the Serpentine Gallery in London that covered the last 50 years of his career. But the e-flux show, despite its diminutive size, is a good introduction to the artist’s ethos, in which objects—and, to some extent, exhibitions—are secondary to activism, engagement, and participation.

Art has not been Metzger’s only or primary concern. He was born in 1926 in Nuremberg to Polish-Jewish parents, and shipped out of Nazi Germany in 1939 on one of the Kindertransport trains that sent about 10,000 children to Great Britain; his parents were killed in the Nazi camps. In 1944, when he was living on a commune, he decided to become an artist rather than a revolutionary. But his revolutionary leanings were never eradicated; instead, they became integral to his art making.

Metzger trained as a painter in the ’40s and ’50s. Then, in 1959, he published the “Auto-Destructive Art Manifesto,” which called for artworks to be produced with industrial materials and have a limited life span. Cardboard boxes were fixed to the walls of a gallery. Canvases and nylon sheets were burned with hydrochloric acid, reducing them to shreds. Metzger described auto-destructive art as “a desperate last-minute subversive political weapon” used by artists in response to the technological buildup of the world’s military powers.

Metzger co-organized the “Destruction in Art Symposium” in London in 1966 and declared an Art Strike from 1977 to 1980. He’s worked with the U.K.-based Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament—but also created perception-bending works like the Liquid Crystal Environment, in which psychedelic images were projected, in some instances, onto rock bands like Cream, the Who, and the Move. More recently, he initiated Reduce Art Flights (RAF), a campaign to get art-world jet-setters to diminish their use of airplanes.

What’s also interesting about his career, however, is that it spans a half-century in which becoming an artist instead of a revolutionary wasn’t so straightforward. Where politically engaged American artists from the ’30s, like Ad Reinhardt, could claim art and politics as separate activities, ’60s artists like Donald Judd started getting called out, often by other artists, for being in collusion with wealthy and powerful individuals and institutions.

In this light, Metzger’s debut at e-flux feels like another chapter in the discussion of art, commerce, and politics, since e-flux itself represents the most recent wave of “progressive,” politically engaged artist entrepreneurship. Anton Vidokle, who founded e-flux, describes it as an “independent, self-financed artist-run project.” But e-flux is also synonymous in the art world with an endless stream of e-mails—sometimes four or five a day, targeted to an estimated 50,000 to 70,000 people—advertising exhibitions, art fairs, biennials, and other events.

In another context, Vidokle would be called a promoter or an agent; here, paid publicity is described as “creating new conditions for production and circulation” in forms that are “less alienating than existing models.” (A hilarious exchange between Vidokle and a Swedish journalist is online at Dossier, where the writer asks, “How big is e-flux in economical terms? What is the approximate yearly turnover?” Vidokle: “Are you kidding me?” Q: “No. I’m from Sweden, a country where all information like that is public.”

But I digress—or, actually, I don’t digress, since Metzger was involved with Fluxus—although, interestingly, he was often excluded from Fluxus events because he wanted to include political content. E-flux obviously cribs from Fluxus: linguistically, for starters. But also because George Maciunas, a founding member of Fluxus, was an early New York–based artist-entrepreneur. Maciunas took over buildings in Soho in the ’60s, registering them with the city as agricultural co-ops and turning them into artist-occupied Fluxhouses, a move that would eventually transform Downtown Manhattan. Members of Orchard, an early Lower East Side artist-run initiative, have cited Maciunas as a progenitor of the LES art-gentrification phenomenon, of which e-flux is a part.

Meanwhile, back in the e-flux basement, you can mine local newspapers and contribute to the current conversation on credit, extinction, and the way we live now. Within the first week, people had put up articles about Ai Weiwei, the Chinese activist-dissident artist being held by the Chinese government—interestingly, within this context, for “economic crimes”; an obituary of Hedda Sterne, the only woman included in The Irascibles, a famous photograph of Abstract Expressionist painters published in 1950 in Life; and an article about U by Kotex Tween, a new sanitary pad marketed for girls eight to 12 years old.

The project will shift and change over time, obviously. Events will become news, and on the magnetic board in the basement, a collective creative response will be generated. Then, perhaps you’ll get an e-flux e-mail like one I received recently for an upcoming symposium in Madrid where “immaterial producers” (that is, artists and critics) will consider new modes of “performing citizenship”—and you might be inclined to read that through a consciousness newly calibrated by Metzger’s work, as well.

—April 27, 2011

“Agitator, In Absentia: This Time, Gustav Metzger Lets His Art Do the Talking”, Observer • Jeannie Rosenfeld

Given Gustav Metzger’s age and international stature, it’s hard to believe that the 85-year-old artist and activist is only now having his first major U.S. exhibition, at the New Museum through July 3, and that it comes on the heels of his first solo presentation this side of the Atlantic, also on the Lower East Side, in the basement gallery of e-flux…

Given Gustav Metzger’s age and international stature, it’s hard to believe that the 85-year-old artist and activist is only now having his first major U.S. exhibition, at the New Museum through July 3, and that it comes on the heels of his first solo presentation this side of the Atlantic, also on the Lower East Side, in the basement gallery of e-flux until July 30.

Whether you’re moved by the elder statesman’s sociopolitical meditations or find them “blunt, heavy-handed and trite,” as Ken Johnson did in the New York Times’s scathing review, Mr. Metzger was a pivotal art-world figure in the 1960’s and has had a burst of activity in the late autumn of his life. But when you consider the intensely political and ephemeral nature of his installations, that Mr. Metzger operates completely outside the confines of the art market, and that he doesn’t travel by plane or even use a computer or telephone, it isn’t really all that surprising that we haven’t seen him here yet.

The artist’s relative obscurity and economy of means intrigued Massimiliano Gioni, associate director of the New Museum, who curated the exhibition and liked the idea of showing “incredibly simple but resonant work somehow done with nothing in a city where everything is super-produced.” Mr. Metzger’s modest, almost frail demeanor belies the breadth and ambition of his output. Born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1926 to Jewish parents from Poland, he was evacuated to England on a 1939 Kindertransport; his mother and father perished. This formative trauma has defined his life and art, inextricably linked in pursuit of radical social change.

Although the Holocaust is treated directly in much of his work, Mr. Metzger’s call to arms across five decades has encompassed avant-garde campaigns against the nuclear and space races, environmental pollution, mass consumption and the commodification of art. As he put it somewhat hyperbolically in 1961, before accepting a jail sentence for civil disobedience: “The situation is now more barbarous than Buchenwald, for there can be absolute obliteration at any moment.”

Artistically, Mr. Metzger first articulated this philosophy in 1959, with his manifesto of what he called Auto-destructive art, in which he proposed primarily public works with lifespans of only a few moments to no more than 20 years. The concept was embodied in his 1961 Acid Nylon painting, which Mr. Metzger demonstrated on London’s Southbank, donning protective clothing and a gas mask as he sprayed hydrochloric acid onto three large colored sheets of nylon stretched over a metal frame, causing the “canvases” to disintegrate. Liquid Crystal Environment, conceived in 1965-66, put forth a more redemptive theory of so-called Auto-creative art, with heated crystals in glass slide frames transforming into kaleidoscopic spectral projections.

The New Museum focuses on more recent—and tangible—art objects, bringing together for the first time in its entirety the 12 sculptural installations from Mr. Metzger’s “Historic Photographs” series, begun in 1990. Featuring iconic images of tragedy from the 20th century that are blown up but then obscured or outright concealed with various materials including fabric, fluorescent lights, bricks and metal, these constructions invite viewers to physically and emotionally engage with catastrophe.

The entry point simulates the experience of the first image encountered, The Ramp at Auschwitz, Summer, 1944, depositing visitors upon weathered wooden planks as they exit the elevators to immediately confront a selection of Hungarian Jews freshly arrived at the death camp. To Crawl Into—Anschluss, Vienna, March 1938 lures viewers underneath a sheet to assume the prostrate position of Jews forced to scrub the pavement in the covered image on the ground.

Mr. Metzger has also taken on as subjects the Oklahoma City bombing, the Vietnam War and a public protest in England, a rather limited range given the otherwise bold scale, always reworking the same dozen images with variations for each setting. Mr. Gioni suggests Mr. Metzger is purposely “cutting through so much visual pollution, trying to stop the cycle of consumption of images, and forcing us to experience those that are most necessary,” but those familiar with the series may crave more.

The initial inspiration for this project was an Italian newspaper photo of Israeli police guarding Arab men heaped on the floor of the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Reappropriated as To Walk Into—Massacre on the Mount, Jerusalem, 8 November 1990, the life-size image draped with linen exemplifies Mr. Metzger’s goal, stated in an interview with associate curator Gary Carrion-Murayari for an accompanying publication, of bringing viewers into “the closest tactile relationship to the photographic environment.” Encouraging visitors without ever coercing them, Mr. Metzger addresses his “fundamental concern”—“to reveal by hiding” with a “search for meaning at the center.”

This experiential element of his project is more significant than the objects themselves, which will be recycled when the exhibition ends. Logistics partly explain why these installations were fabricated on site with local materials and only remote guidance from the artist, given that he has rallied against air flight and never been represented by a gallery, but it also reflects his ethos. The particulars, frugally appointed, vary to suit the audience for maximum effect and are rendered obsolete once they’ve served their purpose, rather than editioned, per art-world custom, to secure their resale value. Even if, like the Times’s Mr. Johnson, you are “mystified … that the international art world intelligentsia has rallied around such punishingly obvious, politically banal, morally bullying and aesthetically enervating work,” you’ve got to marvel at Mr. Metzger’s success despite his staunch independence from protocol, and wonder how he makes a living.

It’s the distinctly ephemeral quality of the sculptures, along with shared source material, that links the New Museum’s larger show, spread across the museum’s fourth floor, to the room-size installation in e-flux’s intimate Essex Street space. A slightly modified recreation of Mass Media: Today and Yesterday from a 2009 retrospective at the Serpentine Gallery in London, the centerpiece is a stack of over 10,000 newspapers representing just about every constituency in the city; at a small desk, visitors are invited to clip articles from local subscriptions related to the topics “credit crunch,” “extinction,” and “the way we live now,” and post them on a bulletin board.

The Serpentine version used Mr. Metzger’s personal collection of newspapers, accumulated since 1995, so those interacting with it could only place entire sheets from the pile onto a stand, to be returned intact when the show closed. At e-flux, project manager Mila Zacharias carefully researched all publications available in New York’s five boroughs to come up with a cross section that includes Spanish-, Yiddish- and Chinese-language papers; the gay, Catholic and political press; and this truth-seeking salmon-colored weekly; in addition to the major dailies. The heap itself, mostly blindly arranged (slight adjustments were made to vary the surface), offers a poetic snapshot of society, featuring both hard news and tabloid fodder, from the Royal Wedding to “lady killer” Raul Barrera, with everything from supermarket circulars and stock prices to luxury goods ads in between.

Since the show opened in mid-April, a steady stream of around 10 visitors a day—large by e-flux standards and not including several big groups—has filled the bulletin board with more deliberate commentary, juxtaposing images, headlines, full articles and isolated words out of context to effects ranging from ironic and poignant to alarming. Admittedly without any guidelines, Ms. Zacharias is regularly clearing the board to make way for more. Here, too, the entire artwork will be recycled at the end of its run, presumably even more easily given its materials.

A recurring motif in Mr. Metzger’s oeuvre, newspapers at once signify a vital source of knowledge and the impossibility of fully absorbing contemporary human experience. As with the magnified archival images at the New Museum, the idea, played out on macro scale, is to motivate a public numbed by the media’s barrage of horrific images and, almost as threatening to the artist, consumerism. Mr. Metzger summed it up in a performance he staged at London’s Tate Modern in 2008, where he randomly mounted pages from the Daily Express onto a gallery wall over three days: “This is the world. Look at it and deal with it,” is how Mr. Metzger described that project.

Compelling as this commentary is, Mr. Metzger’s apparent disregard for newer, digital media and his underlying belief in the enduring power of newsprint comes across as almost quaint. It is somewhat paradoxical that someone so concerned with communication mostly rejects the dominant modes of communication today, especially when these new forms would emphasize his points about our precipitous information age. Then again, this refusal to tune in is in itself quite a feat given that most of us can’t imagine how we managed before Facebook and smartphones. Mr. Metzger’s absence in New York—despite multiple attempts, The Observer was unable to pin him down for an interview—also makes for quieter contemplation in contrast to the more temporal, so-called “public active installations” he has presided over abroad. These, or, better yet, re-enactments of the Acid Nylon and Liquid Crystal demonstrations, would probably resonate more with New York audiences.

Even so, this pair of revelatory shows offers a pivotal overview of an influential artist and his central, still very relevant concerns. And in at least one sense, the impact is more potent without him: no matter that he isn’t present and allows proxies to reconstruct his art from scratch without precise instructions and recycle it when they’re done; here and gone, he suggests, these objects aren’t of lasting value beyond the public’s experience of them.

This thread ties Mr. Metzger’s latest output to his earlier, radical experiments. In the intervening decades, he notoriously declared an art strike, called the Years Without Art, from 1977 to 1980, which led to an extended sabbatical in which he delved into academic research, partook of revolutionary activities, wrote treatises and continued to investigate artistic methods. Whatever the outlet, he never stopped. This latter-day prophet of doom ultimately, and in some ways despite himself, conveys hope, as if there really weren’t any other option but to go up against the forces that would destroy us.

—June 21, 2011