October 13–16, 2016

Where the phrase “gallery weekend” might once have euphemized a romantic indiscretion, or announced a Happening, it now connotes a program of events coordinated to attract a small but influential international audience to a city with aspirations to the status of a cultural hub. Korea’s contribution to this increasingly popular model—adopted in recent years in Barcelona, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Dublin, Vienna, and Warsaw, among others—was composed of three strands: a “showcase exhibition,” a series of talks and guided tours of an art fair, two concurrent biennials, and a selection of local galleries.

The “showcase exhibition” brought together work from 20 South Korean galleries—from such established venues as Seoul’s Hakgojae and Kukje to younger ventures located in the chic Gangnam and Jongno districts—in an awkwardly proportioned exhibition space created by stacking several shipping containers one upon the other. It would have been too much under the circumstances to ask for the exhibition to cohere in aesthetic or conceptual terms, but it did succeed in highlighting some shared preoccupations.

The most striking was a fixation on identity, whether individual, national, or the intersection of the two. Running along the three walls of a recess, Mari Kim’s quasi-psychedelic anime-style portraits insert kawaii female personae—her “Eyedolls”—into a variety of different roles, like a K-pop Cindy Sherman (Farewell My Concubine 3, 2015, is one of a series appropriating Chinese cultural referents, from posters of Mao to contemporary cinema). Lee Seung Hee’s Bamboo (2015), a cluster of five-meter-tall ceramic bamboo stems planted into the concrete floor of the exhibition space, restaged an archetypal South Korean landscape in an environment as far removed from that idyll as could be imagined. In the context of a cultural initiative supported by the national tourist board, the glazed grove read like a neat commentary on the instrumentalization of contemporary art and natural beauty as enticements to foreign investment. Yet it also alluded to the history of Korean pottery and porcelain so magnificently inventoried at the nearby Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, and was indicative of a wider engagement among the artists exhibited with local circumstances and traditions.

The architectural division of the museum—in which an uninspiring hodgepodge of (predominantly European and American) modern and contemporary art is afforded equal billing with an exceptional collection of traditional Korean ceramics, paintings, and calligraphy—offers an analogy for the split cultural inheritance of contemporary South Korean art. Lee Kun-yong’s performances, the subject of a retrospective at Gallery Hyundai, offers one response to that dilemma, sidestepping issues of aesthetic or ideological allegiance in a divided country by seeking to transcend them: as in the Korean monochrome movement that emerged in the postwar period, an impersonal and universalist vision of art is posited as inherently resistant to narrow and repressive social structures. By contrast, Gallery Weekend Korea’s “showcase exhibition” suggests a greater focus on the local and particular—on exploring rather than eclipsing difference—among emerging Korean artists.

The possibility of reconciling a close attention to local conditions with an international appeal was one subject of an illuminating talk at Gallery Weekend Korea by José Kuri, co-founder of Mexico City’s Kurimanzutto. His success in bringing a generation of Mexican artists to the attention of the international art scene, and Kurimanzutto’s contribution to its capital’s burgeoning cultural reputation, were of obvious appeal to Seoul’s aspiring gallerists. Yet his eminently sensible advice (“we opened the gallery because there were artists, not because there were collectors”) was met with some resistance from an audience eager to hear revealed the hidden secrets of commercial success. Kuri’s insistence that young spaces should keep their overheads down (the gallery’s early motto was “cheap, fast, and out of control”) so as to minimize commercial pressures aroused mild hostility, as if it constituted a dereliction of a gallery’s duties to its artists or a failure of ambition. That the success of Kurimanzutto was attributable to its artists’ “going deeper” into Mexican culture wasn’t, consequently, developed. But that it is possible to make a virtue of a marginal position seemed pertinent: the gallery’s program was distinguished, rather than diminished, by its relative independence from global trends.

Anxieties over South Korea’s place in the world resurfaced in the curatorial statement for SeMA Biennale Mediacity, the biennial survey of contemporary art with a focus on new media and technologies. Elaborating on her chosen title—“Neriri Kirurur Harara” is a line from a Shuntarō Tanikawa poem speculating on “what Martians do on their small sphere”1, and expressing hope that contact might be made—artistic director Beck Jee-sook argued that it was even more pressing to “formulate individual and common expectations out of unsought-for inheritances” because South Korea “is marooned in a peninsula-cum-island.” Yet while many readers will sympathize with the desire to find modes of cultural activity that foster links between alienated constituencies,2 the biennale didn’t provide them.

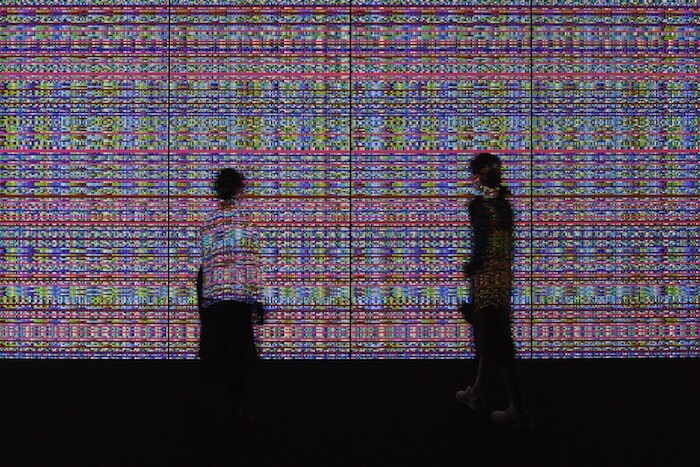

The most striking work at Mediacity instead identified the factors that estrange individuals and communities from each other and the world, without offering up much hope of resolving them. Mounira Al Solh’s video installation The Mute Tongue (2009-10) exposed the violent and racist ideologies embedded in language by inviting a Serbian mime artist to perform a series of Arabic proverbs, while Jeamin Cha’s three-channel video installation Twelve (2016) drew attention to the exclusion of the public from matters of government. The simian protagonist of Pierre Huyghe’s short film Untitled (Human Mask) (2014), abandoned to its fate in deserted Fukushima, offered a powerful indictment of humanity’s failure to empathize with other species or to respect the planet it shares with them, further illustrating the disconnect between those who shape the future and those condemned to suffer the consequences. It was demoralizing to note that the work professing the greatest faith in the possibility of physical and psychological connectedness between sentient beings, Carolee Schneemann’s 16mm film Water Light / Water Needle (Lake Mahwah, NJ) (1966), was made half a century ago. The pervasive sense was of communication interrupted or frustrated, of access to power denied.

The Gwangju Biennale (September 2–November 6, 2016, curated by Maria Lind and reviewed in art-agenda by Hanlu Zhang, and so only touched upon here) posited a more constructive role for art by optimistically identifying it as “The Eighth Climate,” a utopian space in which the immaterial and material worlds are joined, and the former can effect change in the latter. This alluring, if ultimately unconvincing, premise felt like the logical conclusion of the curatorial trend (endemic at biennales) to position art as the nexus at which all things meet: thought and action, digital and IRL, localism and globalism, critique and collusion. Indeed, that an attempt to stimulate a sector of the South Korean economy through the invitation of what amounts to a trade delegation could be labelled a “weekend” itself implies the collapse of divisions between labor and leisure, between cultural production and national economic policy.3

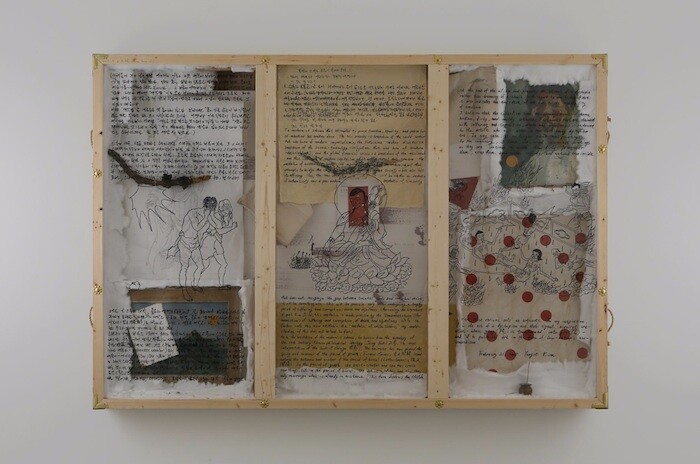

Whether art should seek to dissolve or reassert identities—shore up or break down the boundaries which define individuals, communities, disciplines, and cultures—is a familiar, if suddenly pressing, dilemma. The tentative possibility that this is a false binary was offered up by the recent work of Kim Yong-ik, included in a retrospective at Seoul’s Ilmin Museum of Art (“Closer… Come Closer…,” September 1–November 6, 2016). Kim participated in the two movements that did much to define contemporary Korean culture and society—Danseakhwa and the Minjung struggle for democracy—and his latest assemblage works (such as Ksitigrabha-1, 2015) resembled simply crafted but elaborately decorated reliquaries in which were encased his own paintings. The glass covers of the works in this “coffin series” were inscribed with writing and esoteric symbols encapsulating 40 years devoted to the reconciliation of the artist’s aesthetic and ethical principles through philosophical investigation and social work. These intensely personal reflections on a life nearing its end nonetheless depend for their effect upon the persistence of shared values and communicable traditions: the individual indivisible from community.

Translation by Takaka U. Lento, who renders the poem’s title as “Two Billion Light Years of Loneliness.”

The week of November 7 saw (among other presidential crises) hundreds of thousands of South Koreans take to the street to demand the resignation of President Park Geun-hye over an administrative scandal.

Gallery Weekend Korea opened on a Thursday afternoon and lasted for four days, featuring two “networking receptions,” three panel discussions on the art market, a lanyard-wearing troupe of “international art professionals,” and a congratulatory address from Cho Yoon-sun, the Minister of Culture, Sports, and Tourism.