Leonore Mau, Der Fischmarkt und die Fische. © bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau.

Water masses moving disquietingly, rhythmically absorbing the rocks. Formless, immeasurable ocean waves. Like the breath of a vast living environment, mounting and descending, dissolving in a thousand moving shapes of sea foam. In Alice Guy-Blaché’s 1906 film Ocean Studies, the camera carefully documents the moving morphology of the sea. Guy recorded these images during her journey through Spain in the fall of 1905, where she and her cameraman, Anatole Thiberville, produced a number of silent and sound films for the French Gaumont Film Company.

Ocean Studies opens a plane of immanence where object and gaze, sensing and thinking, coincide: an immanence of forms and forces, a morphology in motion where cinema discovers one of its fundamental principles. This is how, for Jean Epstein, cinema’s ability to morph stable forms, to name beyond language, went hand in hand with its dissolution of identities and its dislocation of boundaries: “The world of the screen … constitutes the privileged domain of the malleable, the viscous, and the liquid.” 1

The sensorial intimacy of the visual fluidity invokes the oceanic not only as a constitutive element of cinema but as its major epistemic operator:

In movement … fundamental principles of formal logic are mobilized, relaxed, wrecked, reduced to a very relative validity. In the screen world, where things never remain what they are, how would the principle of identity keep its rigor? The principle of identity presupposes a homogeneous space- time continuum, in which figures remain superimposable onto themselves… . When all forms liquefy in a perpetual mobility, the principle of identity becomes as unsuitable to them as it is to ocean waves. 2

These liquid images—a logic from the “viewpoint of fusion” (de point de fusion)—become tangible in Epstein’s cinematic cycle Poèmes Bretons, seven films made between 1928 and 1948. Epstein understood the ocean not only as an intense and concrete milieu but also as a specific medium. In this sense, Brittany’s inhabitants were for him the initial and immediate point of access to the oceanic. Against any essentialist stance, Epstein conceived of such qualities as a projection of their experience within this particular environment. His films attempted to assimilate—through cinema’s capacity to produce movement—the fluid mediality of the milieu, revealed in the concrete gestures, bodily rhythms, and vocal intonations of those living by the sea.

In 1964, the German duo Hubert Fichte and Leonore Mau spent a few months in the Portuguese fishing village Sesimbra. It was the first trip the queer writer-ethnologist and photographer undertook on their entangled geographic and artistic trajectory, which later led them through South and Central America and several countries in Africa. Der Fischmarkt und die Fische (The Fish Market and the Fish, 1964) is the second of four collaborative photo films—that is, films composed of photographic stills—Fichte and Mau produced for different German state television channels between 1966 and 1971. Combining materialist analysis with an inscription of desire into knowledge, the films proceed from Fichte’s ethnopoetic method: a dialectics between document and sensitivity, language and sexuality.

Der Fischmarkt constructs a complex ecology—a political ecology of the sea— that, through montage, alludes to the silencing of colonial crimes and tortures of prisoners during the Estado Novo, a corporatist regime that controlled Portugal from 1933 to 1974. Using the second person, the film narrates the labor and living conditions of a young fisherman. With an astonishing directness that oscillates between diary and documentary report, the voice-over evokes scenes from his life:

Your parents did not have enough money to send you and your brother to high school. For one it would have been enough. They didn’t want to privilege either of you. Both of you had to start working at ten or twelve. 3

While the images were made in Sesimbra during António de Oliveira Salazar’s dictatorship, the film was not released until 1968, the year Salazar was removed from power. Moreover, the film was censored by the West German regional state due to the country’s close economic and geopolitical relationship with the dictator. Consequently, several political references from the original storyboard are missing from the version that now exists.4

Leonore Mau, Der Fischmarkt und die Fische. © bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau.

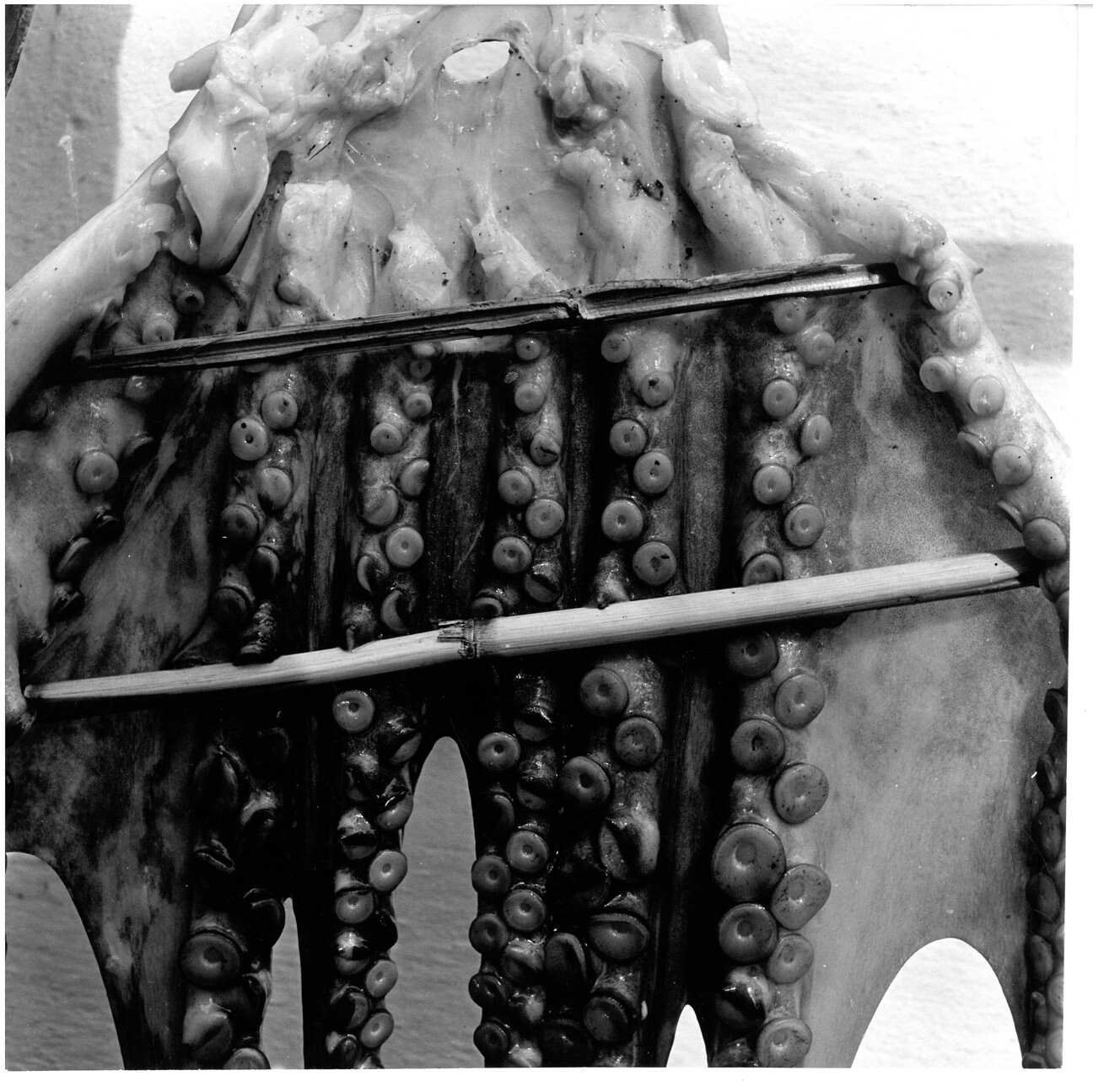

Der Fischmarkt introduces multiple strong cesurae which operate by means of gradual dissociation between the visual and the acoustic planes. The rhythmic continuum traversing both planes—the poetic voice-over and images—allows for their reciprocal alteration and, consequently, for an intensification of their sensuous-affective impact. While in the first part of the film the images of the daily labor and leisure of the village inhabitants correspond with the descriptive tone of the voice-over, this association breaks in the film’s second part, when a long procession of fish corpses in different forms and dimensions appears. Rather than providing a narrative element, the fish bodies are an uncanny and intrusive deviation from the storyline. Such a drifting trajectory, which reinforces the dissociation of the planes, goes hand in hand with a complex formal arrangement, a montage of maritime attractions.

Leonore Mau, Der Fischmarkt und die Fische. © bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau.

Through this morphology of sea creatures, Fichte and Mau construct a political argument that yields a strong sensorial and poetic effect. It is precisely this ecological excess of the sea that suddenly turns the daily business, the fished fish (German: “Fang”) into prisoners (“Gefangene”), political torture victims that the film alludes to without narrating them. 5

A suit costs two hundred marks.

If the catch is good, you can buy yourself a nice shirt.

If you get sick, the Fishermen’s Fund pays eight escudos for three days, six escudos for two days, and later four escudos.

Yes, political prisoners are tortured.

Yes, there are spies everywhere.

Why are you telling me this?We trust foreigners.

Or you are perfectly satisfied with the government.We fishermen are better off!

Yes, I believe in the miracle of Fátima.

Or you don’t believe in the miracle of Fátima.6

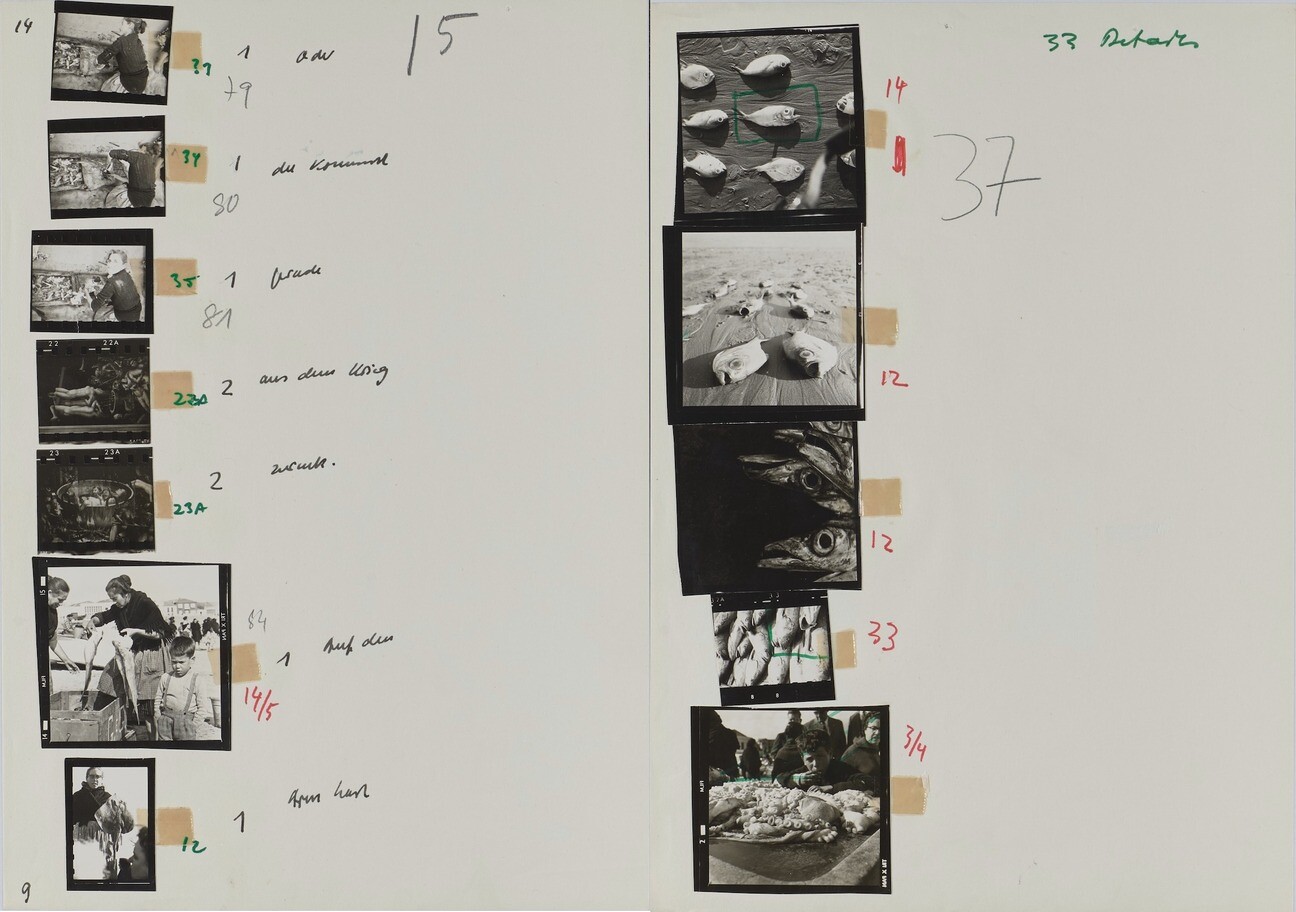

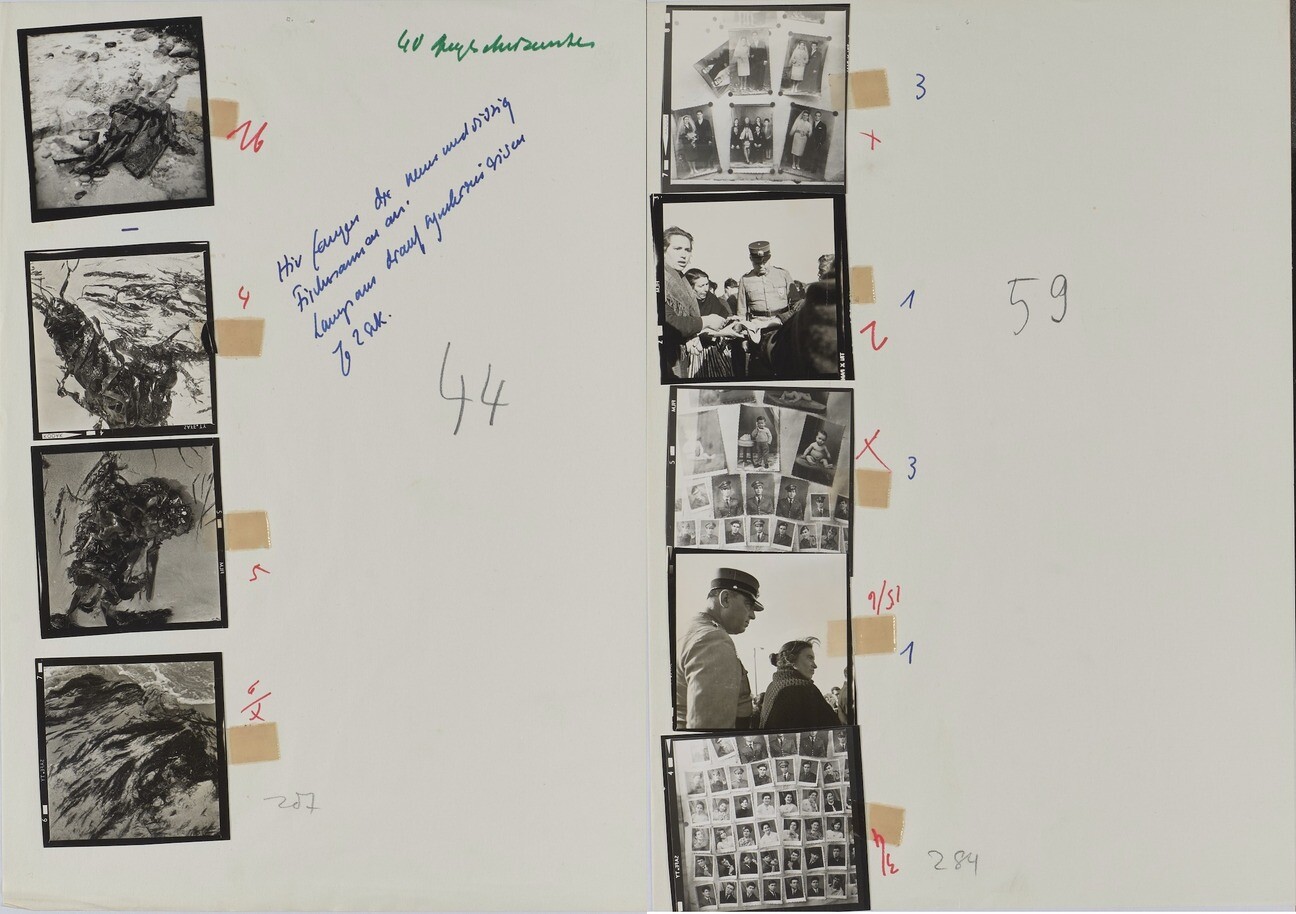

Fichte’s voice, speaking off-screen, shifts perspectives without altering its intonation. The experimental and formal complexity of the visual montage accompanied by these speech acts should be read in juxtaposition with the storyboard. Composed of a vertical arrangement of images with comments on the right, its first pages document the village population. Like Epstein for his Poèmes Bretons, Fichte and Mau work with non-professional actors. The villagers of different generations are seen from the back or in frontal portraits, laying on the beach or standing by their catch. Mau’s camera records their gestures and facial expressions in their singularity. Like Epstein, who posited a “hidden mark” of the ocean mediated through the social life around the sea, Fichte and Mau emphasize the fluidity of the relations that unfold in this maritime environment.

Yet in Fichte and Mau’s film, unlike Epstein’s Poèmes Bretons, the uncanny atmosphere does not result from the nameless uncertainty of the sea, but is rather fueled by a state of political paranoia. While the voice-over reports on the fishermen’s living conditions, policemen appear among the population of the fish market. Fichte and Mau thus make a concise inscription referring to the repressions of Salazar’s fascist regime and its colonial war.

Storyboard for the photo film Der Fischmarkt und die Fische, © S. Fischer Stiftung / Nachlass Hubert Fichte

Framed by images of a woman cutting fish, the storyboard displays two photographic prints of Inferno, a painting from the sixteenth century by an unknown Portuguese master which offers a mediaeval scenario staging the eternal torments of the deadly sins. Three naked female bodies hang upside down with their heads in fire; a group of men boil alive in a cauldron. Even though these images disappear from the film, their relation to the Angolan War of Independence remains in the voice-over: “You come back straight from the war. On your arm you’ve tattooed the word ‘Angola.’” Another detail of the painting shows Lucifer wearing a costume and a headdress of feathers reminiscent of the Brazilian Indigenous population; the figure holds an ivory horn from Benin. Even in this underworld, the Black body is deprived of humanity. The painting’s racist figuration, namely its identification of the demonic with non-white colonized bodies, couldn’t have escaped Fichte and Mau. In her text Black Metamorphosis: New Natives in a New World, Sylvia Wynter frames such a systematic mythical “construction of a world in which Africa became the negation of all humanity, the heart of darkness” as “Sepulveda-syndrome,” a reference to the legitimation of colonial conquest by the sixteenth century Spanish theologian Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda.7

Fichte and Mau further develop this visual technique of intrusion in their later ethnographic work as a critique of the western (neo)colonial imposition of “objectivity.” The pair takes a morphological stance: the fish shown in a long sequence and later cited in a list of names evoke a fragmentation and disintegration of meaning. The more the attention shifts to the fish corpses, the more they become autonomous agents.

Leonore Mau, Der Fischmarkt und die Fische. © bpk / S. Fischer Stiftung / Leonore Mau

The storyboard mentions the Portuguese Fado, a traditional musical genre that expresses saudade, a feeling of mourning due to the loss of someone close. In the film, this musical element is reduced to a punctual sound of the triangle, one of Fado’s signature instruments. Through their montage, Fichte and Mau operate with elements reminiscent of the uncanny milieus of Jean Painlevé’s underwater films. Similar to the French microcinematographer’s surreal underwater landscapes, enlargement and fragmentation of the fish here produce all kinds of unsettling effects. However, in contrast to Painlevé’, Der Fischmarkt politically engages the environment through its splintered and broken nature. Like in Walter Benjamin’s allegorical play, the exposed mortality and decay introduce a historical awareness. They speak of the political ruination of history. The cinematic dialectic of Fang and Gefangene, fragmented fish and imprisoned bodies, goes beyond a mere rhetorical operation, be it metaphor or a metonymy. These images affect not as a parable to be translated back into a signified but, in their ruined presence, as concrete, irreducible images. This relocation of suffering yields an effect of intensification, pushing the potential of the photo film beyond its limit. While the narrative plane is suddenly interpolated by the excessive corporeality of the fish, the morphological focus on the maritime milieu dialectically captures its opposite: a body in a standstill of agony. This immobilized agony corresponds to the primal quality of the photo film.

Storyboard for the photo film Der Fischmarkt und die Fische, © S. Fischer Stiftung / Nachlass Hubert Fichte

Yet Fichte and Mau’s morphological montage reveals more than the images can do by themselves. In the interval, the space in-between, the commonsense identity of things dissolves. In these intervals between the images, the political ecology becomes tangible. This strong morphological focus involves the maritime milieu as a medium. The final sequence from the storyboard gives insight into the potential dissolution and ruination of forms, providing more images of formlessness amidst the maritime landscape. Displayed on five pages of the storyboard, these views are captioned as “Angeschwemmtes,” that which is “washed ashore.”8 These concrete images of algae, seashells, sand, and dead fish scattered on the beach paradoxically render even more diffuse and blurred all that which can be washed up, brought in from the sea.

This diffuse and formless matter raises the question of metamorphosis and its temporalization as a radical state of transition beyond identity or name. Calling instead of describing; conjuring forces within words and forms in equal measure. “Here start the forty-nine names of fish,” announces the storyboard’s caption. The voice-over reads them aloud:

“Espadarte. Peixe Agulha. Toninha. Agua Faz. Peixe Espada. Cabaçao …”9

Jean Epstein, Epstein, “Le Cinéma du diable,” in Écrits sur le cinéma, 1921-1953: édition chronologique en deux volumes. Tome 1: 1921-1947, ed. Pierre Lherminier (Paris: Cinéma Club/Seghers, 1975), 347.

Jean Epstein, “Esprit de Cinema. The Logic of Images,” in Critical Essays and New Translations, ed. Sarah Keller and Jason N. Paul, trans. Thao Nguyen (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012), 331.

Hubert Fichte and Leonore Mau, Der Fischmarkt und die Fische (1968), black-and-white, 9 minutes.

West Germany’s postwar relationship with Salazar’s Portugal was primarily shaped by anti-Communist alignment, economic cooperation, and pragmatic diplomacy. In particular, in this Cold War period, Germany censored critique of Portugal’s colonial policies in Africa. Fichte and Mau’s film was commissioned by the regional state television channel Norddeutscher Rundfunk. On the censorship of the film see: Nathalie David, “Auf den filmischen Spuren von Sie und Er. Leonore Mau und Hubert Fichte,” in Viva Fotofilm bewegt/unbewegt, ed. Gusztáv Hámos, Katja Pratschke, and Thomas Tode (Bielefeld: Schüren Verlag, 2009), 251–258. See also Arne Bunk’s beautiful analysis of the film, “Vom Meeresgrund schauen uns Augen an,” in Hubert Fichtes Medien, ed. Karin Krauthausen and Stephan Kammer (Zurich–Berlin: diaphanes, 2014) 93–110.

In his radio feature Sonorer mehrsprachiger Prospekt über Antonio de Oliveira Salazar (A Sonorous Multilingual Brochure About António de Oliveira Salazar), as well as in his posthumously published novel Eine glückliche Liebe (A Happy Love), Fichte is more explicit about the tortures of prisoners and political repressions in Portugal, elements which remain a seismic allusion in the film.

Fichte and Mau, Der Fischmarkt und die Fische

Sylvia Wynter, Black Metamorphosis: New Natives in a New World, unpublished manuscript written in 1970s, preserved in the Institute of the Black World at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York.

Storyboard for the photo film Der Fischmarkt und die Fische, © S. Fischer Stiftung / Nachlass Hubert Fichte.

Fichte and Mau, Der Fischmarkt und die Fische.