At the risk of immediately doing away with any probity or intellectual credibility whatsoever, I have to confess that the last thing I watched on my computer before landing in Los Angeles was an old episode of “Keeping up with the Kardashians” featuring the over-the-top wedding of Kim Kardashian and Kanye West. Upon arrival at LAX airport, the first thing I saw while leaving the Tom Bradley Terminal was Kanye West himself, tucked in a 400,000-dollar white Rolls Royce blasting tracks from his soon-to-be-released and eagerly awaited album WAVES.

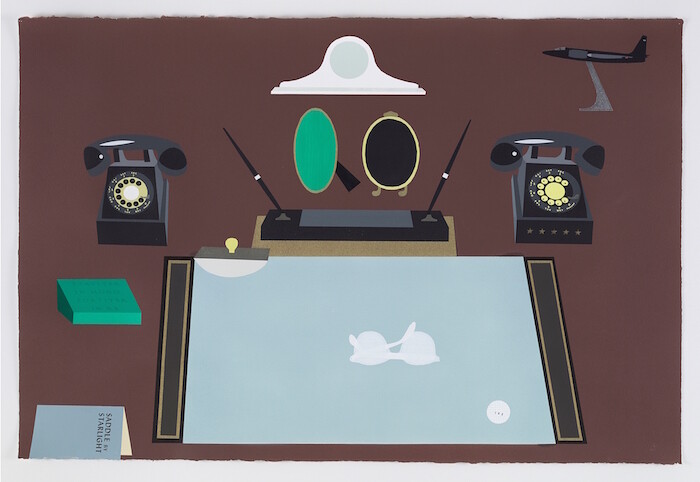

This instant of serendipity reminded me of how Los Angeles is, in the words of Jean Baudrillard, hyperreal—a place that doesn’t allow consciousness to distinguish reality from its simulation. Not by coincidence, and confirming the relevance of the French theorist’s thought to a city such as LA, Chateau Shatto is currently exhibiting “Jean Baudrillard’s photography: Ultimate Paradox,” an exhibition of his own photographic works. The city’s hyperreality seemed to be the overarching theme of both the handful of art fairs taking place around town as well as that of the art itself. Art Los Angeles Contemporary (ALAC), the big-ticket stalwart located in a repurposed hangar of Santa Monica Airport, might be the closest I’ve come to the grim reality of a corporate art convention: narrow alleys, grey carpets, white neon, overpriced food, no fanciful props but certainly some standout artworks, including those at local gallery David Kordansky’s booth, which presented an engaging solo project by Matthew Brannon. In a series of large graphic prints (Net Assessment, 2015, Oval Officer, 2015, and Chipped Teeth, 2016), Brannon depicts American presidents’s desks at the White House during the Vietnam War, underlining how everyday objects co-exist alongside decisions that would usher in a new era of American foreign policy. Though seemingly antiseptic, the presentation was a very apropos critique in the era of an all-too-real presidential candidate Donald Trump and unequivocal war campaigning.

Apart from Kordansky, most of the works that attracted my attention from the cramped hallways were in tune with the dreamlike atmosphere I ascribed to the city: Samara Golden’s topsy-turvy upside down domestic landscape installations both at Canada, New York, and Night Gallery, Los Angeles, consisted of set and decorated tables weightlessly installed on a vertical plane, resulting in a dizzying, familiar-yet-strange vision. Some other happy surprises included the flowery fantasy paintings (all Untitled, various dates) of Berlin-based transgender artist, writer, singer, and dancer Juwelia, who is both the author and subject of her unique practice. New York’s Jack Hanley Gallery insightfully paired her acrylics on canvas with the no-less-disquieting and poignant female figures of the younger New York-based sculptor Elizabeth Jaeger.

At the other end of the spectrum entirely from ALAC’s clinical concourses was Paramount Ranch, the less-of-a-fair-than-a-community-street-festival event, tucked into the Santa Monica Mountains north of Malibu. The eponymous Western film set that once served as the backdrop for the 1990s TV series “Dr Quinn, Medicine Woman” hosted (sadly rumored to be for the last time) nearly 60 galleries, nonprofits, and artist-run spaces within its sun-drenched (Saturday) then flooded (Sunday) wooden porches and barns as well as some outdoor open-air locations. This year’s coup de maître was pulled off by LA gallery The Box, which installed Tree (2014), Paul McCarthy’s monumental 79-foot-tall inflatable green sculpture. The work was the unfortunate protagonist of the 2014 edition of FIAC in Paris, where its public exhibition at Place Vendôme angered conservative protesters for “resembling” a butt plug; the work was vandalized and deflated, and the artist assaulted. Seeing the gigantic green inflatable appear in the hills from afar felt like experiencing a science-fiction relic translated from Paris’s nineteenth-century edifices to LA’s mountains. Within the context of a fair and of a film set, it felt much less controversial, almost like a prop that provided an uncanny visual backdrop to the weekend’s performances, including the deeply elegant and subtly orchestrated piece by choreographer and dancer Ligia Lewis, organized by the local nonprofit space Fahrenheit.

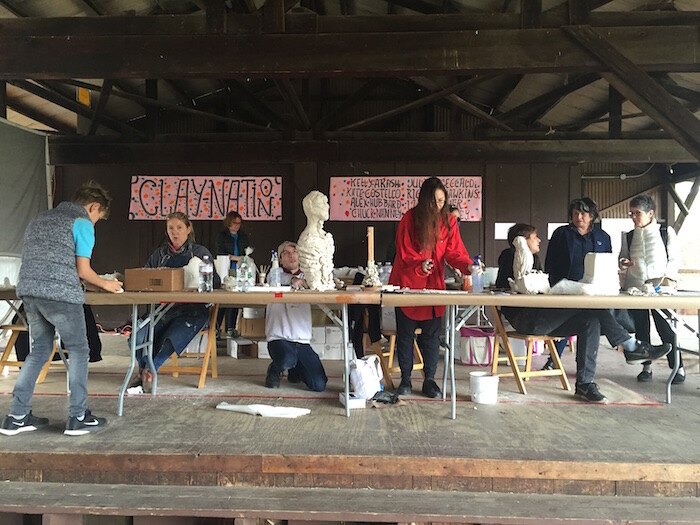

Among the wooden structures, New York’s Maccarone displayed Danny McDonald’s collectibles—figures, props, and other appropriated Hollywood paraphernalia—while fair co-organizers Freedman Fitzpatrick assembled sculptures from Mathis Altmann that grafted disparate elements into miniature blocks of concrete. Other standouts were those projects that took the event’s informality and playfulness as a point of departure for unconventional ways to show (and sell) art. Among them were the monumental outdoor presentation of Jannis Varelas’s brightly colored paintings with Athens gallery The Breeder; Andrea Zittel’s High Desert Test Site Gem/Mineral Expo and Painted Rock Auction, a market of desert gems and minerals; and the live sculpting event “ClayNation,” organized by artist Richard Hawkins. Local Del Vaz Projects (in collaboration with Flash Art editor Patrick Steffen) presented a group installation on the outskirts of the fair comprising a black ATV; bold mannequins wearing sexy swimsuits by Mishkan Swim; carpets by Sophie Stone; sculptures by Natalie Jones; paintings by Nahuel Vecino; and haircuts by Lydia Hwang on an outstanding chair made by Jessi Reaves with discarded upholstery foam. It couldn’t get any more refreshingly absurdist, and yet there it was and there it worked.