Like dance draws lines in space and time, Andrea Geyer’s first solo exhibition in Mexico City leaves a pleasant yet evanescent memory. Through crisscrossing imaginary and factual lines, the artist connects past histories and current politics with a sharp focus on the role of women in the arts. Encompassing a variety of media, such as video installation, photographic collage, and painting, “Truly Spun Never” is a theatrical show without being solemn or inviting the blues.

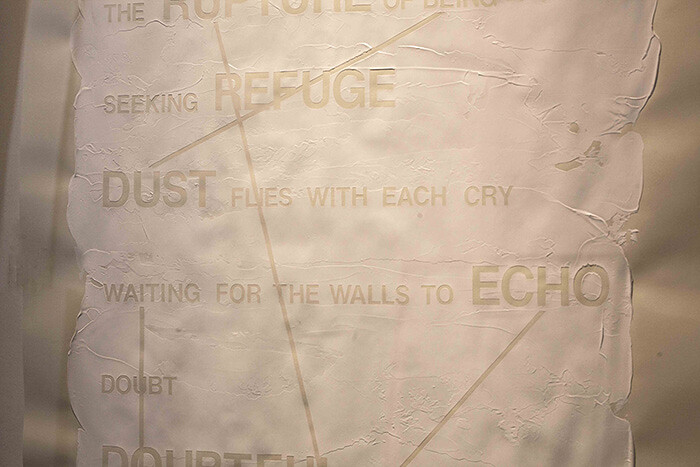

Entering the exhibition space, viewers can see four large-scale framed white paintings (Travels on Slender Thread 2–5, 2015) interspersed with black-and-white photographs lining the walls of the gallery’s foyer. Lazily leaning against the walls, the text-based paintings that constitute Travels all feature poems written by the artist, based on her extensive research into women’s under-recognized contributions to modernism. The texts themselves are dry, but their design, with two different sizes of fonts, suggests movement and different tones or tempos; interconnecting graphic lines imply the variety of modes of reading a single thing or fact.

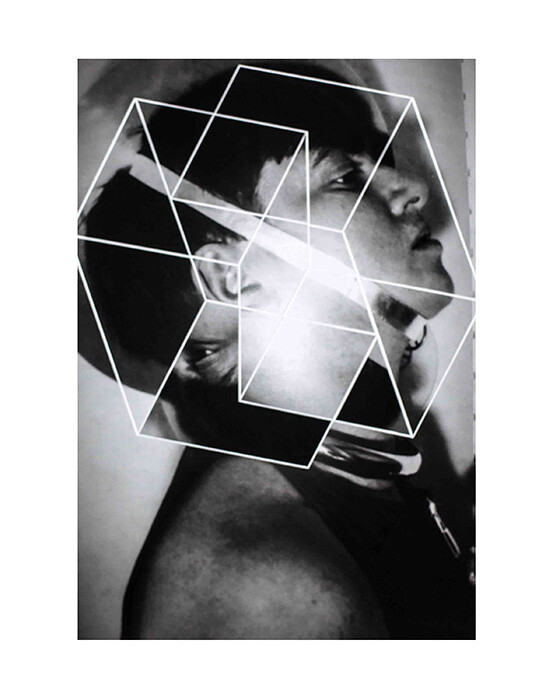

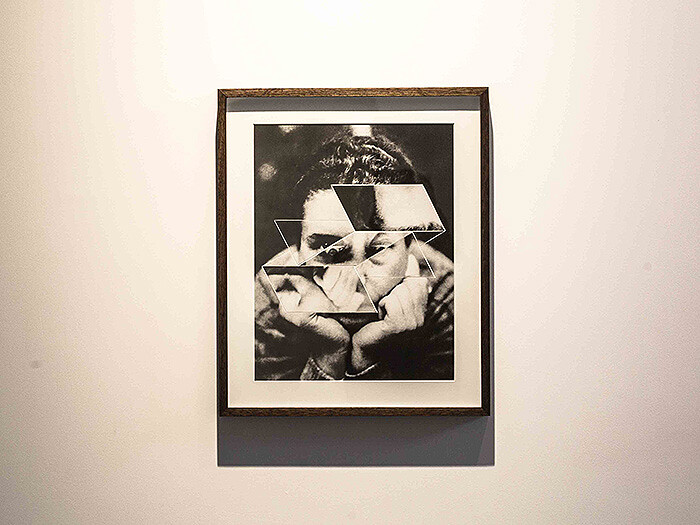

Hung on the walls is the more effective “Asterism” series (2016): historical portraits of women who contributed to the Bauhaus—such as artists Anni Albers, Marianne Brandt, Gertrud Arndt, Lucia Moholy, and Grete Stern—all deconstructed and reassembled under Josef Albers’s Structural Constellations (c. 1950-60), which consist of symmetric configurations of straight lines. In these charming collages, the artists’ faces look like pieces of a misplaced puzzle: eyes and mouth as forehead, arms upside down. Fragmented and uncanny, the images of these creative women who, alongside their partners and colleagues, developed experimental practices, could evoke the relatively minor attention they received compared with their male counterparts. Their achievements are dispersed or unrecognized, such as their faces in the photographs distorted by a kaleidoscopic effect.

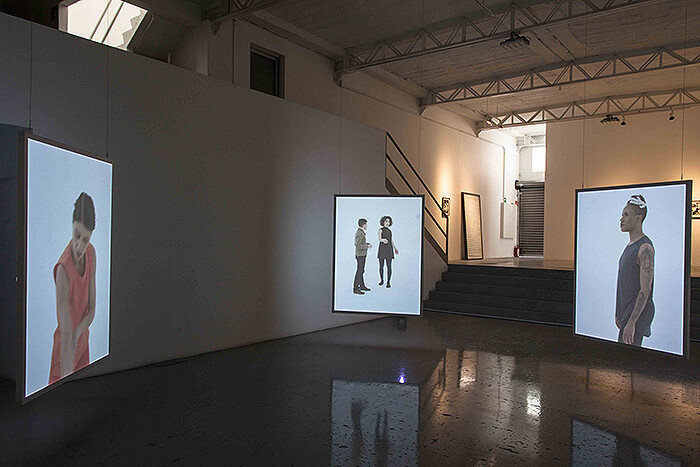

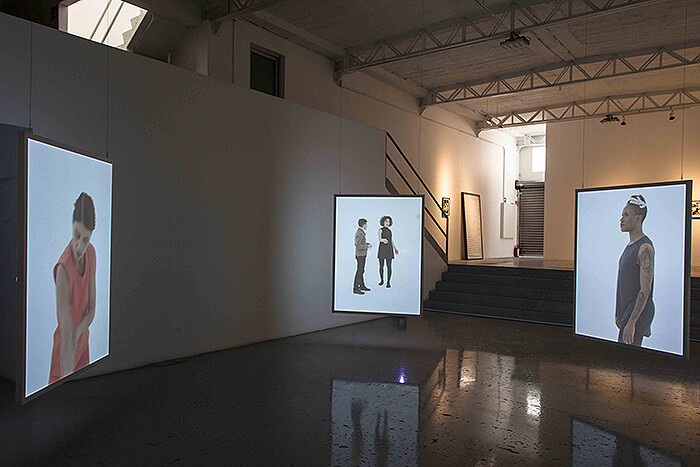

Geyer’s new video installation Truly Spun Never (2016)—a 17-minute looped video displayed across three projection screens, installed at various angles in the center of the main gallery—also directs attention to the history of modern art in Germany, in this case focusing in particular on Ausdruckstanz, or Expressionist Dance. Originating in the early 1900s, Ausdruckstanz was a response to traditional forms, specifically to ballet, which was perceived as rigid technical virtuosity and simple entertainment. Appealing to natural movements, emotions, and sensuality, “German dance”—as it was designated during the Third Reich—was curiously considered by the Nazi regime as non-degenerate while other Expressionist art forms, such as painting, were banned. The reason: sexual liberation in dance served as a smokescreen for the repressive sexual politics of the state, including the persecution of homoerotic practices and women’s responsibility for maintaining the vitality of a race.1 For this film, Geyer created a script using her signature method of assembling a variety of contemporaneous writings—including poems by Paul Celan, from which the work takes its title2, from the 1959 collection Sprachgitter [Speech-Grille].]—and texts on dance by theorists and dancers Rudolf Laban and Mary Wigman, and Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. The dialogue is uttered directly to the viewer by a young critic while six dancers—all of different ethnicities and who identify as women, possibly representing those who would have been persecuted during Nazi Germany—dance, respond to the discursive narration, and move elegantly between the three screens.

Following the expressionist style, the solo choreographies are guided by the performer’s feelings: they’re intuitive and gentle pirouettes that, mixed with the impassioned tone of the narrator, induce in the spectator a mesmerized calm. Movements and language—and in this work also poetry and identity—interact to shed light onto the political history of Ausdruckstanz, its contamination by politics, and its instrumentalization at the hands of the state. Furthermore, the piece refers to the government’s intervention into the private space of the body, using the body as a social site that fluctuates according to the whim of national ideologies, where women’s bodies in particular act as an icon of modern sexuality and independence, and yet are subject to persecution. “What is its rhythm to time? What is rhythm to ideology?” asks the installation’s script. Geyer’s evocative piece looks into the semantic labyrinth between culture and ideology as well as the relations between bodies and politics, fluid and nonetheless significant for identity. The viewer is left with questions about a particular moment in history, and the fate of its actors, through an elegant exercise in memory and art.

Terri J. Gordon, “Fascism and the Female Form: Performance Art in the Third Reich,” in Sexuality and German Fascism, ed. Dagmar Herzog (Berghahn Books, 2004), 164–200.

Geyer’s work takes it title from Paul Celan’s poem titled “Schliere” [Streaks