“Queerness is not yet here”—at least according to José Esteban Muñoz, who in his book Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009) argues that queer aesthetics is fundamentally utopic. The same could be said for much of Ad Minoliti’s work, in which queer exchanges are understood not as acts of performativity between humans but as interactions between non-human forms and things, thus potentially structuring the social parameters of a future yet to come. Minoliti’s practice is concerned with painting as a space of resistance, in which gender-neutral relations manifest in anthropomorphic geometric entities that inhabit the tropes of modernist painting, design, and architecture, and, in doing so, unintentionally echo the all too familiar notion of failure often attached to modernist utopias. Ad Minoliti, formerly Adriana Minoliti (the artist recently started going by “Ad” instead of her full first name in an effort to avoid gender identification, thereby claiming gender neutrality), lives and works in Buenos Aires, where she is the co-founder of PintorAs, a feminist collective of 20 young Argentinian artists.

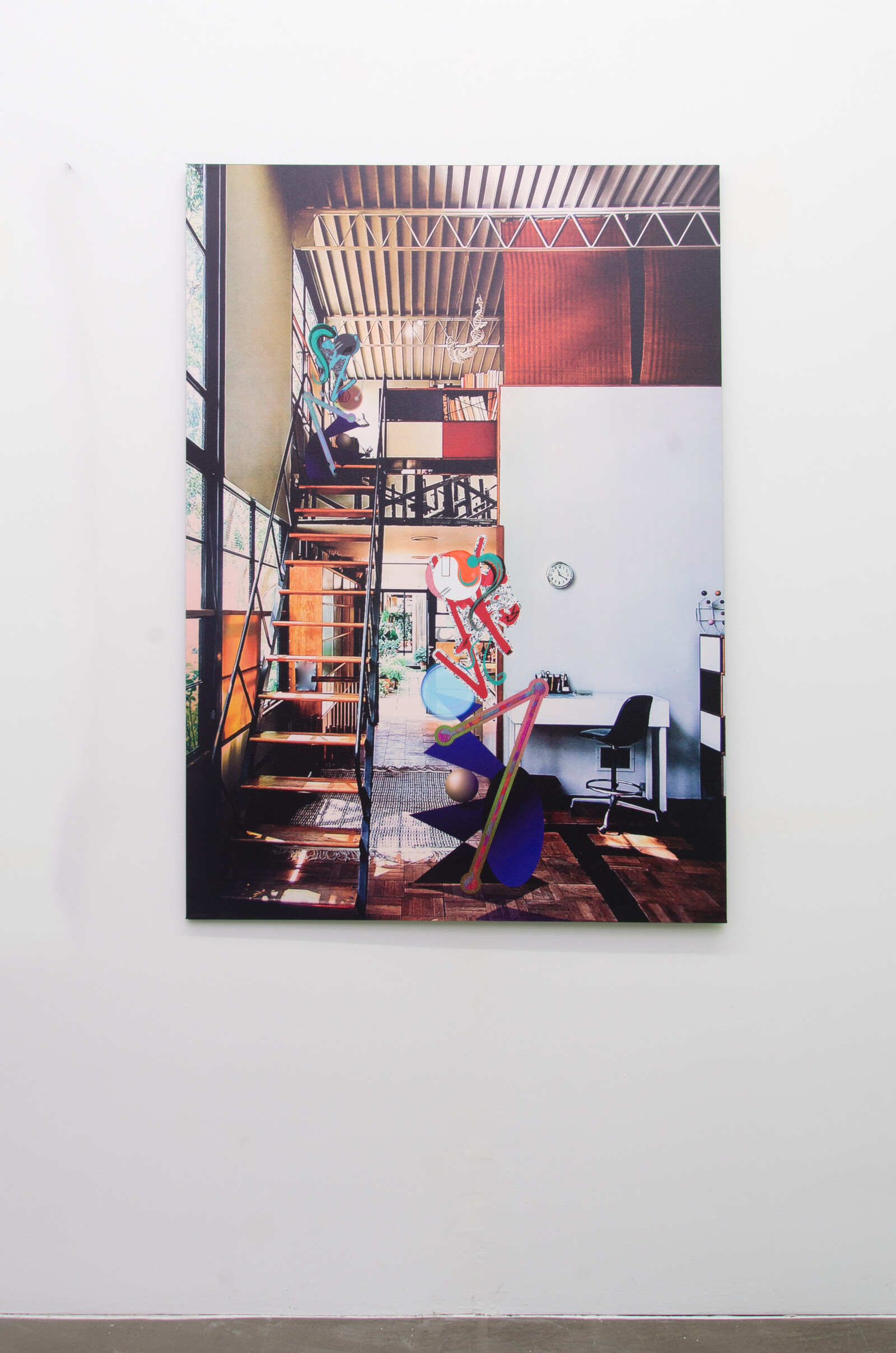

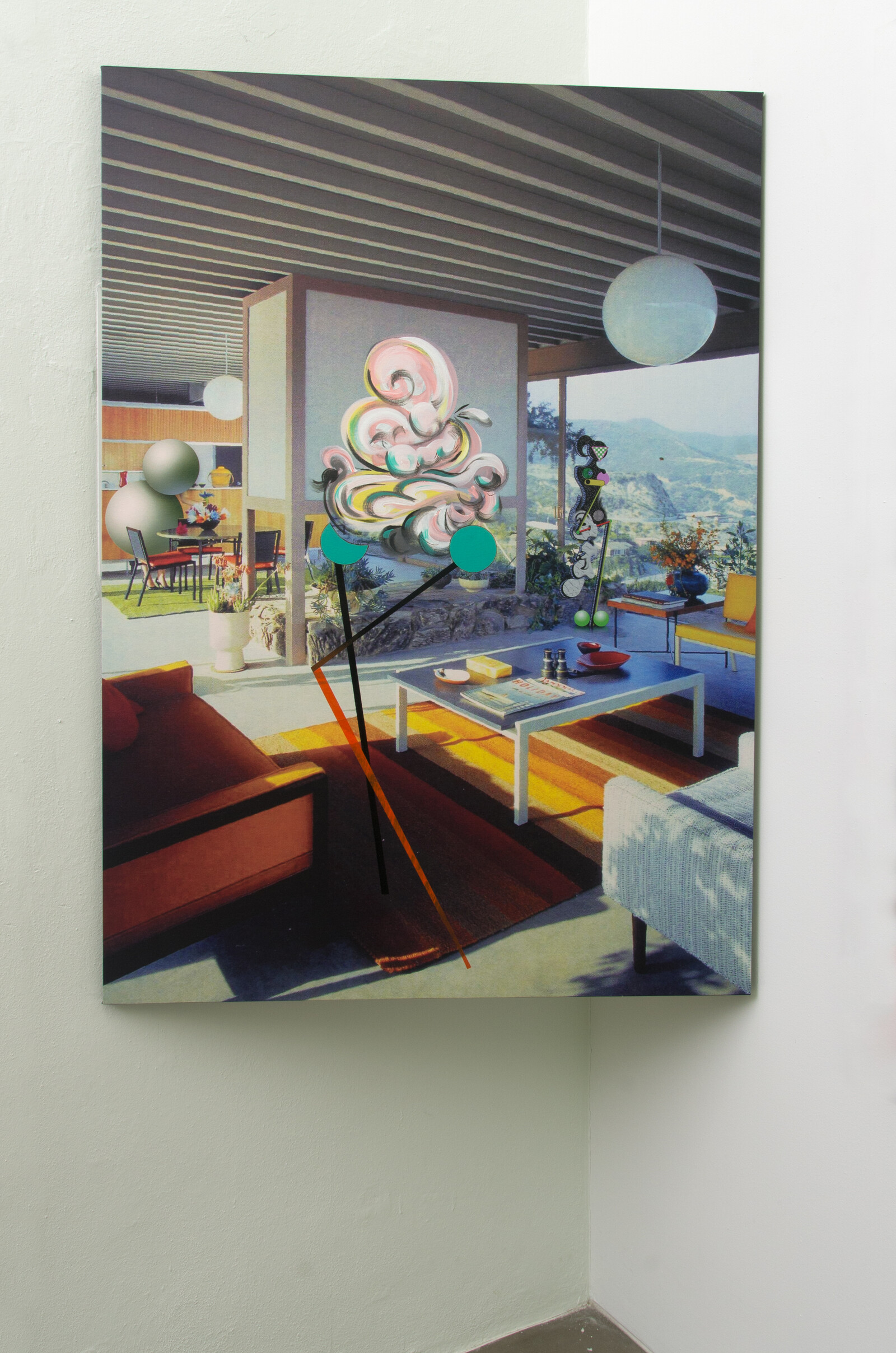

Inspired by the Case Study Houses (1945–1966), a project conceived to supply affordable and efficient housing to soldiers returning to the U.S. after the war, Minolitti turned the space of the gallery into the omitted Case Study House No. 14. Out of the 36 designs commissioned to prominent California architects, only 26 houses were actually built and none were mass-produced. What has been incessantly reproduced in popular culture is the streamlined and glamorous imaginary of postwar California suburbia and its heteronormativity. This is partially due to Julius Shulman’s photographs of the houses, whose translated sleek designs into a bourgeois lifestyle geared toward clearly stratified gender relationships: women are often depicted lounging on sofas or performing tasks in the kitchen, while men are usually presented standing up or being catered to by women. Minoliti uses these images as source material for four digital collages printed on canvas, which conform part of a display intended to mimic a domestic space, as these digital compositions comprise representations of Minoliti’s domestic utopia, where interior design meets chic queer futurity.

Much like Shulman’s photographs, the domesticity in “CSH#14_utopía” is staged and somewhat theatrical. Take CSH_21 (all works 2015), where Minoliti digitally replaces a seated woman and a man with a sphere and geometric composition from Shulman’s original photograph of Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House No. 21. A stylish and manicured hand remains from the source image, casually leaning on the sofa, a leisurely gesture that points to the construction of gender roles in images through deliberate positioning; the wedding ring on the woman’s finger in Shulman’s photograph is digitally transformed into an eye. CSH_22, based on the photograph of Case Study House No. 22 (also by Pierre Koenig), is able to better neutralize differences, testing the viewer’s own predispositions toward gender determination and form (what part of the gendered body could a triangle or a circle represent?). Whereas Shulman’s image assembles difference through gendered roles—a woman in a dress is depicted arranging a bouquet of flowers—Minoliti does it through form, replacing bodies with geometric shapes and subsequently adding additional elements to the finished digital composition with acrylic paint and marker. CSH_8 and CSH_9 place bodies where none are depicted. In any case, it’s difficult to disassociate these images from the ubiquity of mid-century modern architecture and design in high-fashion editorials, which often represents women as objects of desire and contemplation.

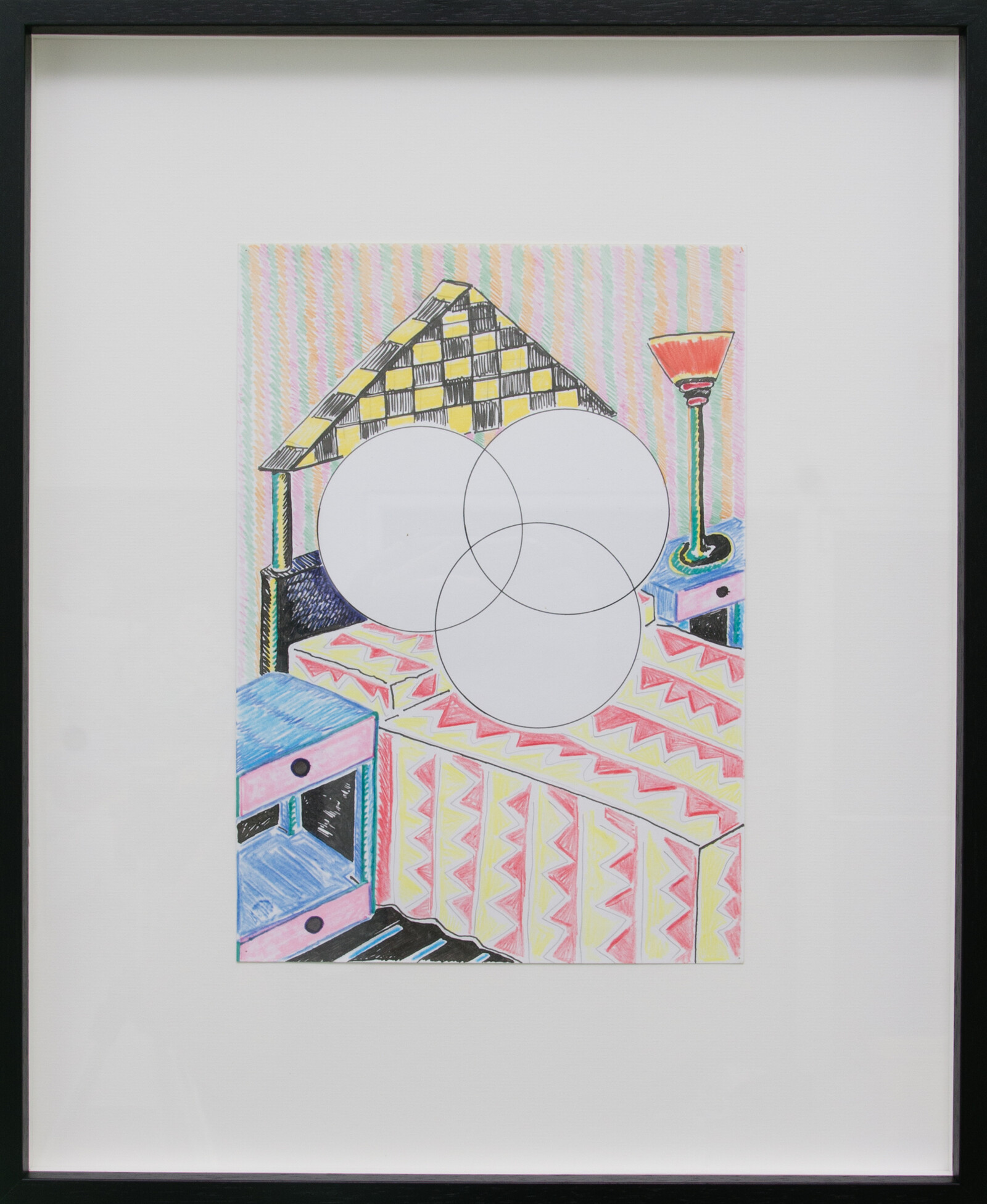

In other works, such as the diptych composed by the acrylic paintings Primavera (Spring) and Otoño (Fall), the refusal of gender-specificity through geometry is speculative. Here it is less about a fixed narrative than about a space where the physical world and geometric invention coexist. Here and there we catch a glimpse of what might be an identifiable body, as Minoliti always leaves something to that effect as a fleeting moment of recognition. Primavera features a group of geometric forms existing in an exuberant and vibrant landscape, while in Otoño, a complex composition is thrust mid-air by what appears to be a leg. Their titles echoing Minoliti’s physical displacement from Buenos Aires to San Juan, cities with opposite seasons, the two paintings of a female and a male season disrupt conventions of nature-culture divide.

Feminist, queer, and environmental theories, namely Donna Haraway’s proposal for the reinvention of nature present in A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), are combined with aesthetic references that are altogether sourced from a male-dominated canon. It is a mash-up of metaphysical and surrealist painting, notably Giorgio di Chirico and Roberto Aizenberg, with traces of MADÍ’s irregular geometric forms and the movement’s emphasis on “invention” (MADÍ stood for “Movement, Abstraction, Dimension, Invention”), which is roughly translated into Minoliti’s ambition toward a universal transhumanity through the conversion of bodies into geometry.

But even if Minoliti subverts a predominantly male Western painting tradition by occupying and populating it with geometric cyborgs, it also inherits and potentially reproduces the ideology of its aesthetic codes based on gender, race, and class, something visible in Tea Time, an installation that comprises a wall painting, the work Miss Rosa [Miss Pink], which consists of a painting siting on a round, metallic chair, and a well-ordered line of cups on the ground. The painting’s pink color meets the chair’s pink grid (perhaps a symbol of this hybrid modernity?), both set against the mint green wall. Like Shulman’s images, where leisure activities conceal domestic forms of labor, everyday life is pleasant and carefree in Minoliti’s new world order.

At times more or less explicit, Minoliti’s revised modernity reminds us that we are constantly performing gender roles in a space codified for normative sociality. Geometry as a gender-bending strategy might be completely unattainable. Yet reclaimed utopian visions within the modern canon usually are.